The failure of real incomes to grow over a sustained period in some of the world’s richest countries has caused policy-makers to explore, once again, whether capitalism is working – particularly for middle and lower income working households.

Policies on pay, productivity and taxation are under review – except, perhaps, in Brexit-distracted Britain. But when it comes to living standards, it’s generally assumed that there is little that can usefully be done to boost real incomes by cutting living costs. This assumption is mostly correct as politicians have limited power to control the non-tax price of a car or, for example, the weekly food shop.

This assumption, however, is not necessarily a sound one for one of the largest components of the household budget – housing.

Over the last 40 years, we’ve seen massive divergence in house price growth across the developed world. There’s been little to no real growth in countries such as Germany and France, but soaring value in the UK, Australia and Spain. Indeed, in 2014, The Economist calculated that if general inflation had kept pace with UK house price inflation since the 1970s, a British chicken would now be priced at £51.

These soaring prices have had a major impact on both real incomes and home ownership.

The Resolution Foundation has estimated that over the period 2002 to 2015 rising housing costs effectively “wiped out” most, if not all, of the modest real income gains made by the lowest earning 56% of UK working age households. And they calculated that a two-earner couple with one child have suffered a “housing costs loss” equivalent to putting 9 pence on the basic rate of tax, over the period since the early 1990s.

The extraordinary rise in UK house prices has had other undesirable effects. Home ownership rates have plummeted – particularly for younger households. Astonishingly, home ownership is now at a 30 year low – and not necessarily from choice. The proportion of working-age households owning a home with a mortgage fell from around 55% in 2000 to just 41% in 2015. The proportion in (generally more expensive and less stable) private rented housing has soared from 11% to 25% over this period.

The generational impact is acute – today’s 30 year olds are only half as likely to own their own homes as the “baby boomers” of the 1950s/60s. Four out of ten 30 year olds now live in private rented accommodation, compared with 1 in 10 just 50 years ago – and housing costs now absorb twice the share of income for this age group, compared with the “baby boomer” experience.

These trends are not only part of the living standards squeeze – they also pose considerable fiscal risks, if a large proportion of the population do not own their homes and remain reliant on housing benefit in retirement. And as young people are increasingly dependent on family members to help with the costs of house purchase, unequal housing access and housing inflation are also likely to become strong drivers of greater economic inequality.

There is nothing accidental about high UK house prices – we simply aren’t building enough homes to meet population growth and shrinkage of household size. Annual house-building in the UK is roughly half the level of 50 years ago – with private house building failing to rise to compensate for the near ending of local authority building[1. According to the Office of National Statistics and its quarterly report on new builds.].

The UK’s planning system is simply not as responsive to demand as that in many other countries, including those with a similar population density. And UK politicians have a tendency to rely upon ad hoc initiatives and large sounding but low delivering amounts of extra government subsidy to boost home building.

The present UK government seems willing to consider more radical options to increase home building, but as yet there are few signs that what is planned is on the scale to reverse recent affordability trends. Additional home building is often very unpopular, with strong “NIMBY”sentiment, even among those who are recent beneficiaries of new housing on greenfield sites.

To make a real difference to housing numbers, any policy shift needs to be big.

Firstly, more land needs to be made available for development and this may require a series of carrots and sticks:

- Local councils need to have strong economic incentives to approve additional development, and increased confidence that they can use powers of compulsory purchase where this appears necessary.

- The government could also consider further direct economic incentives on land-owners – applying a significant tax charge to land approved for development, and/or stronger incentives for landowners offering land up for development.

- In exchange, infrastructure requirements on new developments could be socialised – with the government funding these from its own capital investment budgets, rather than imposing an infrastructure “tax” on developers.

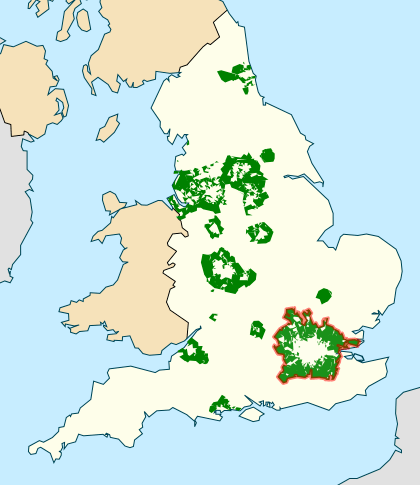

Secondly, the government needs to consider freeing up some of the existing “green belt” land, which is often sited where demand for new housing is greatest. Much of the green belt was established shortly after the Second World War, in wholly different demographic circumstances. It accounts for a large part of the land area of England – 1.6m hectares or 13%. It accounts for an even larger part of the land areas where there is greatest housing demand.

Clearly some of this green belt covers areas of outstanding natural beauty, where development should sensibly be resisted. But much green belt land, including around London, is really nothing special – and is arguably too extensive. London’s green belt is now three times larger than London itself.

Understandably, politicians are petrified of raising the prospect of axing green belt land. I remember the issue being discussed inside the Coalition government in 2014, with civil servants regarding the case for reform as unanswerable, while we politicians sat paralysed – envisaging the storm of well-heeled protest that would follow any announcement of change.

The only way to proceed is to establish a wide-ranging independent review of green belt policy – looking at what land might sensibly be freed up in areas of high housing demand, and possibly “swapping” this for new “green belt” in other areas.

Finally, we need to consider whether there is a role for more investment in social housing – possibly through shared ownership routes (and certainly while avoiding a return to a heavily subsidised housing type where the main route of entry was to demonstrate inability to self-house). It is the collapse of social sector provision since the mid-1970s that accounts for a large part of the reduction in housing supply (see chart above). It seems unlikely that we can reverse current trends without a greater social sector contribution.

Governments in developed capitalist countries now face a challenge to demonstrate, not least to low and middle income working households, that capitalism can go on meeting their economic needs. Tax reform can help. Pay and productivity are crucial – but the policy levers are less obvious. In countries such as the UK, with grossly inflated housing costs, governments have an excellent opportunity to improve real income growth by making the housing market work effectively. This will take some political courage. But if free market solutions cannot be made to work, it should be no surprise if voters are tempted to return to big government solutions.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe