18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China -Dong Fang, via Wikimedia Commons

Nothing will have been left to chance as the 19th National Congress of China’s Communist Party commences on Wednesday.

Critics and dissenters will long ago have been summoned for a conversation with the security services; the Chongqing successor of his disgraced enemy Bo Xilai has vanished; and, in recent weeks, four People’s Liberation Army generals have been reminded who is boss – by being purged. Additionally, WhatsApp has ceased to work in China[1. Hannah Kuchler, Emily Feng ‘WhatsApp messaging service hit by full blockage in China’ Financial Times 26 September 2017 and Chris Buckley, Steven Lee Myers ‘Xi Jinping Presses Military Overhaul, and Two Generals Disappear’ New York Times 11 October 2017].

In restive Tibet and Xinjiang, the police are now the biggest local employer, with outposts at 500 yard intervals in the cities, and a GPS tracker in every bus, car or tractor to pre-empt terror attacks. Provincial petitioners against local abuses are aware of the existence of ad hoc basement jails in the capital, set up by those they are petitioning against.[2. Chinese security arrangements in Tibet and the XUAR see Adrian Zenz ‘Chen Quanguo: The Strongman Behind Beijing’s Securitization Strategy in Tibet and Xinjiang’ Jamestown Foundation China Brief 21 September 2017]

In addition to the huge police presence, and the world’s most advanced application of big data, 170 million CCTV cameras, and facial recognition technology, an estimated 1.4 million ‘volunteer vigilantes’ are routinely deployed in the big cities to ensure order at even a trade Expo, never mind an event involving a party whose membership exceeds the population of Germany, with a further 87 million in its Youth League.

The National Congress is an important occasion, held every five years, because on the last day, the newest additions to the seven member Standing Committee of the Politburo will be revealed as they troop onto the podium. The party practices a ‘seven up, eight down rule’, meaning 68 year olds have to retire, while all new appointees have to be younger than 67, regardless of how old they will be in 2022.[3. Richard McGregor ‘Xi Jinping’s Moment’ Lowy Institute (October 2017) p.6]

General Secretary and President Xi Jinping (64) and state premier Li Keqiang (62) will remain in post for their second five year term, in a system where the party Central Committee occupies the southern end of the Zhongnanhai government complex inside the Forbidden City, while the State Council occupies the north. Nothing has been done to indicate that Xi wishes to extend a term of office that ends in 2022. Indeed he will be more aware than most that in a system where past ‘core leaders’ like Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin have acted as backseat drivers long after their formal retirement, the smart move is to practice a becoming modesty by stepping down when his term expires.

Were Xi to wish to perpetuate his rule beyond 2022, he would have prepared the ground for the Party or public in advance. That would have meant signaling that the 69 year old historian Wang Qishan, the party’s top disciplinary watchdog who models himself on Frank Underwood in House of Cards, would stay on. Nor would Xi be about to promote two ‘sixth generation’ figures, Chen Mi’ner and Hu Chunhua, who are being groomed for the very top in five years. Three other men are likely to have their mandates renewed.[4. For astute studies of Beijing ‘Kremlinology’ see Andrei Lungu ‘China’s Next President: Reading the Tea Leaves of Chinese Politics’ The Diplomat 29 September 2017 and ‘China’s 19th Party Congress: Projecting the Next Politburo Standing Committee’ The Diplomat 6 October 2017.]

President Xi is the most powerful ‘core leader’ China has had since Mao Zedong. The term ‘core leader’ was invented by Deng Xiaoping to shore up Jiang Zemin after Tiananmen Square, and then retroactively applied to Mao. Hu Jintao, Xi’s predecessor, was never described as such. So far he has amassed ten separate titles, including ‘commander-in-chief’ of the country’s 2.3 million strong armed forces. But it is control of the party that really counts.

Naïve westerners like Rupert Murdoch claimed that the CP was ‘invisible’ in today’s China, even though a red telephone, encrypted and with a four digit number, connects anyone who is anyone in China… and you had better pick up when it buzzes.[6. Richard McGregor, The Party. The Secret World of China’s Communist Rulers (London 2012) is outstanding on how the CCP works.] Xi is busy emphasising traditional Confucian aspects of his ‘thought’, for like Mao he is the only Chinese leader to be identified with ‘thought’ rather than mere ‘theory’ (see my earlier piece; “Is President Xi a moralist like Gertrude Himmelfarb?“).

He is a loyal son of the Party, for his father Xi Zhongxun was one of the original revolutionary leaders around Mao. Xi grew up with the Red elite’s sense of entitlement, including attendance at the kindergarten in Zhongnanhai, only for Xi senior to be rusticated to Yan’an during the Cultural Revolution. Xi himself was consigned to a village where peasants lived in flea-ridden caves.[7. See ‘Portrait of Vice President Xi Jinping’ Wikileaks Public Library of US Diplomacy for an anonymous State Department portrait dated 16 November 2016] Despite being a ‘red princeling’ with a glamorous army folksinger wife who was more famous than he and a daughter who studied at Harvard, Xi is a modest man, with simple tastes, like the hearty stews they cook in the country’s north.[8. On Xi Jinping Thought see Willy Wo-Lap Lam ‘What is Xi Jinping Thought?’ Jamestown Foundation China Brief 21 September 2017. The best biography is by Kerry Brown, CEO, China. The Rise of Xi Jinping (London 2016) but see also Evan Osnos’ ‘Born Red’, The New Yorker 6 April 2015]

Although westerners are obsessed with China’s growing might on the world stage, the reality is that the Party-state’s focus is on a vastly populous country undergoing titanic transformations, and with its own restive regions, wayward peripheries, ageing demographic, not to mention natural disasters and chronic pollution. Xi’s key aim is to ready the party for the centenary of its founding in 2021, the year before he retires, and for 2049, the centenary of the establishment of the People’s Republic under Party rule. Hence the relentless anti-corruption campaign which is not abating.

The economy is well on track to meet its 6.5% annual growth target, while the Party is tightening its grip on debt-laden provincial and local governments, an overheated property market, and on the private sector’s overseas acquisitions binge. Although Xi’s detailed economic planning will not be revealed until next year’s Party Plenum, the guiding ambition is called ‘Made in China, 2025’ with its emphasis on robotics, semiconductors and electric vehicles, where China already accounts for 45% of the world’s total sales.[9. ‘China Show More Signs of Economic Strength Heading Into Communist Party Congress’ Wall Street Journal 13 October 2017 and Charles Clover ‘Electric Cars; China’s highly charged power play’ Financial Times 12 October 2017.]

Then there is China at large. In essence, China wants the US out of Asia-Pacific – where as the late Lee Kwan Yew said; America is just visiting – so that it can deal with the region’s countries on a unilateral basis, bringing its economic and military might to bear in the respective cases of South Korea and Japan. It has already successfully detached Burma, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and the Philippines, while Australia, Malaysia and Singapore are hedging their bets, which oddly leaves (Communist) Vietnam as America’s most reliable ally (for few should rely on India).[10. The best recent account of regional power-plays is by Richard McGregor, Asia’s Reckoning. China, Japan and the Fate of US Power in the Pacific Century (New York 2017). See also Nguyen Minh Quang’s ‘The Bitter Legacy of the 1979 China-Vietnam War’, The Diplomat, 23 February 2017 and on Malaysia see Keith Zhai and PooiKoon Chong’s ‘China Wants This Malaysian Port to Rival Singapore (and that’s not all)’, Bloomberg News, 31 July 2017]

Elsewhere, China seeks to promote win-win relations based on shared economic interests and subscription to multilateral institutions, which China simply replicates to ensure its own version of historic US ‘exceptionalism’, meaning encouraging others to join a club whose rules you ignore yourself.[11. On this theme see Michael Burleigh’s The Best of Times, The Worst of Times. A History of Now (London 2017)]

The comedic Corleone-Trump administration has provided Xi with any number of open goals, from flouncing out of the Trans Pacific Partnership and Paris Climate Change Agreement to withdrawing from UNESCO. Xi’s wife, Peng Liyuan, is already a UNESCO special envoy and China is the agency’s third largest funder, a role that may soon increase. Beijing has just modestly withdrawn its own candidate to lead UNESCO in favour of an Egyptian, knowing that Egypt is a big player in both Africa and the Arab world.[12. ‘China withdraws candidate to lead UNESCO in wake of US pull-out’ South China Morning Post 13 October 2017] Trump’s decision to ‘de-certificate’ the nuclear deal with Iran also benefits China, in so far as this will result in a further rift between the US and Europe, with Beijing on the side of those seeking to maintain what is a solemn US Security Council agreement, which might have been the template for dealing with North Korea, which actually has ‘The Bomb’.

Last but not least, every daily rift between the EU and US simply makes China seem like a more predictable partner, especially as there is no strategic competition over rocks and reefs (involving roughly 6 square kms in an ocean of 1.4 million square kms), and their trade exceeds €1 billion per day. Judicious application of a fraction of China’s overseas investment can incline the likes of the Czech Republic, Greece, Ireland and Portugal to lean their way when sensitive issues come up for an EU vote.[13. Laurens Cerulus and Jakob Hanke ‘Enter the Dragon’ Politico Europe 4 October 2017 is excellent on how the 2008 crisis has left some EU countries vulnerable to Chinese financial influence. On the worried US response see Corey Cooper ‘China’s Europe Game Should Worry the US’ Real Clear World 26 July 2017. I forgo the opportunity to comment on where all of this will leave Brexit Britain and its ‘golden era’ with Xi’s China.]

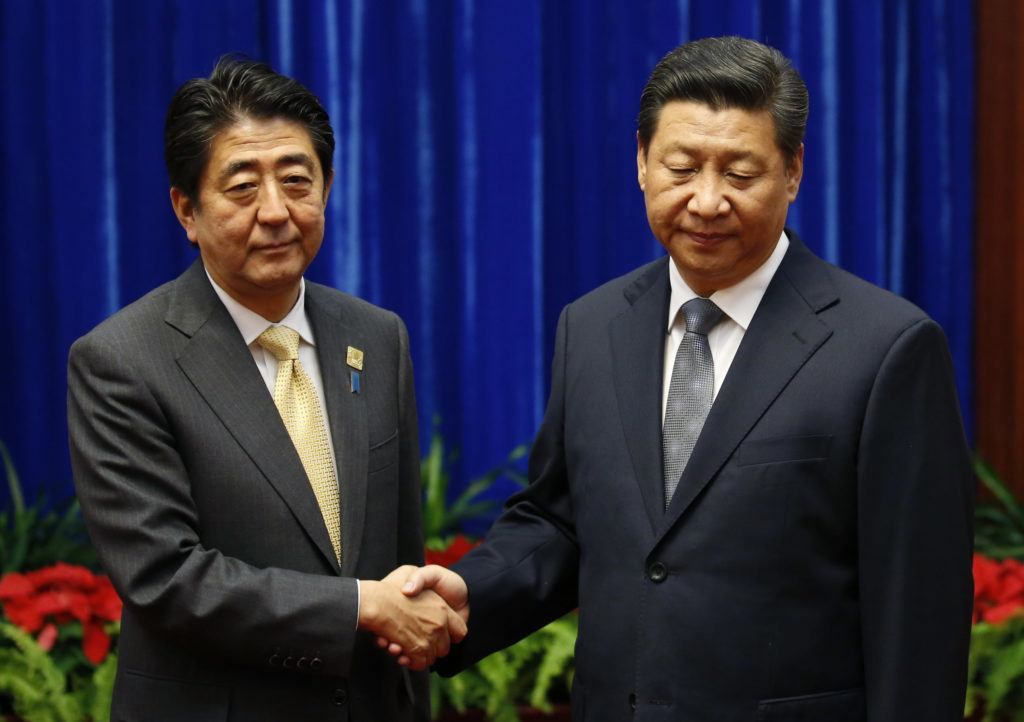

President Xi does not smile much and his words are few. He uses his eyes and body language to devastating effect. In 2014 he finally condescended to meet Japan’s extended hyper nationalist prime minister Shinzo Abe at a Pacific Rim summit. Xi extended his right hand which Abe took, then turned away, forcing Abe to cross his arm over his chest. Xi’s face looked like he was touching a decayed fish (below).

History was a major part of the problem. It is one clue as to the most important dilemma Xi faces. China’s rise has been accompanied by increased emphasis on its (historic) victim status (which Mao and Deng ignored) and the ‘sensitivities’ of 1.4 billion people, which paradoxically have left an authoritarian state partially captive to its own chauvinists. Now that China is on the threshold of being the world’s greatest power, the hardest change will be to act both judiciously and magnanimously, rather than letting history be the master rather than teacher, while eschewing the overweening arrogance of an America with a moron as president.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe