(170919) — NAY PYI TAW, Sept. 19, 2017 (Xinhua) — Myanmar State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi delivers a speech at the Myanmar International Convention Center-2 in Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar, Sept. 19, 2017. Aung San Suu Kyi on Tuesday called on the international community to cooperate for constructively tackling the issue of the northern Rakhine state. (Xinhua/U Aung) (jmmn)

Rohingya horror in Myanmar

The news about the current crisis of violence and displacement seemed to come out of nowhere, when it burst onto our TV screens in August. But if you follow international – and particularly humanitarian – news, you had been hearing about it for weeks before, when the Myamnar regime threatened to refuse entry to UN investigators probing Rohingya abuses. Last year, we saw similar violence and as many as 8,000 Rohingya were believed to be stranded at sea during 2015.

The religious and ethnic tensions go back a long way, and Burma (or Myanmar, as it’s often called by humanitarian organisations) has long been a difficult place for Muslims to live. The Rohingya people are famously homeless, being acknowledged neither by Burma or Bangladesh, and the Buddhist nation refuses to acknowledge their ethnicity in official tallies. Former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan had headed the Rakhine Advisory Commission, which published a 63-page report noting that the Rohingya make up the world’s largest single stateless community.

We’re now seeing widespread criticism of Aung San Suu Kiu’s leadership, despite her having previously been lauded as a human rights champion, and even the former peace campaigner has been said to be disparaging about Muslims, allegedly grumbling last year that the BBC chose to send Mishal Husain to interview her about ethnic and religious tensions: ‘No one told me I was going to be interviewed by a Muslim’.

This explainer from the New Yorker’s Hannah Beech outlines the rocky road of Aung San Suu Kyi’s rise to, and fall from, public acclaim.

To spot emerging humanitarian stories, sign up to news bulletins like DAWNS Digest, subscribe to Reuters World emails, and take note of news coming from NGOs like Human Rights Watch or UN agencies like UNHCR.

And follow writers like UnHerd’s Ben Rogers for religious freedom news from Asia, the Washington Post’s Greg Miller for some of the best coverage of security issues (I recommend his 2015 analysis of Boko Haram , exploring the notion of a global grand caliphate), Ruth Maclean for Africa updates, especially relating to religion, AFP’s Jerome Taylor for pics and stories from South East Asia, and the BBC’s Quentin Sommerville for excellent Middle East commentary.

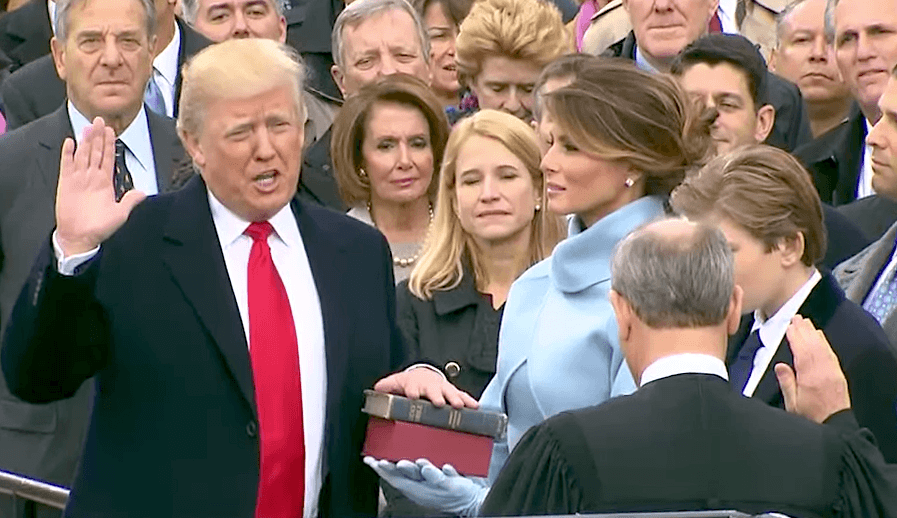

Trump and the (white) evangelicals

There has been much wailing and gnashing of teeth from Christians around the world, and in the US itself, about the strong links between Trump and some conservative evangelical leaders. In voting for him, they prioritised the pro-life issue over respect for women and arguably inspired Trump to issue executive orders on immigration which were perceived by many to be anti-Muslim. The link has become so entrenched that when Russell Moore, president of the Southern Baptist Convention’s policy wing, criticised Trump for having ‘a track record that is unbelievably out of step with what gospel Christians believe’ his comments brought threatened withdrawal of SBC funding from 100 member churches.

Counterintuitive though this support may seem to those us outside the US, there’s a story spanning four or more decades behind it. Still within living memory are the times that US evangelicals interpreted Bible verses relating to being ‘set apart’ to mean living in a much more separatist way than they do now, and engaging with politics was seen as ‘worldly’. It wasn’t until 1979 that Jerry Falwell founded Moral Majority, to mobilise evangelicals to campaign against the social and lifestyle changes which threatened their way of life, and it’s his son Jerry Falwell Jr who is often seen at Trump’s side. Within those two generations of the Falwell family, evangelical churches have moved from the shadows to being described as ‘the new super PACs’.

And there’s an emerging theology which validates this President, moving away from endorsing him on specific issues (with the exception of the travel ban and the Charlottesville violence, which produced slight wobbles but also even louder support from Jerry Falwell Jr) towards an overall lauding of Trump as divinely appointed. The notion that he could be ‘used by God’ despite his well-known moral failings draws on Biblical parallels from the book of Daniel, where the enemy King Nebuchadnezzar inadvertently brings about God’s purposes and is described by God as ‘my servant’(Jeremiah 25:9, if you want to look it up). The new Christian Nationalism school of thought goes on to declare that God will protect the USA because Trump is President.

Read more about this narrative in a Twitter thread by Jack Jenkins.