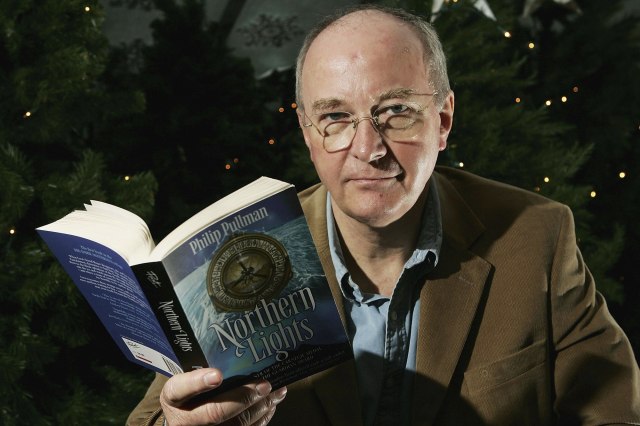

MJ Kim/Getty Images

Few children’s books feature on the radar so far as adults are concerned, with the immortal and obvious exception of Harry Potter. Philip Pullman is another exception – not only is he the Harry Potter of the Guardian classes; he’s the saviour of the book industry, at least up to Christmas. His latest work, La Belle Sauvage, the first instalment of a trilogy called The Book of Dust, launched this week and it’s had the highest pre-launch sales of any book since Harry Potter and the Cursed Child; Waterstones says it’s looking forward to £8 million in sales.

It’s a prequel to His Dark Materials, a trilogy that includes, midway through, the Death of God. That’s right; the Ancient of Days, an old, old man, simply pegs it. This isn’t any old fantasy; it’s an assault on organised religion, specifically Christianity, more specifically, Catholicism. The enemy is something called the Magisterium – the Vatican, now relocated to Geneva (to get Calvinism in the frame); its agents an outfit called the CCD, the Consistorial Court of Discipline, “an agency of the church concerned with heresy and unbelief”. The Inquisition, in other words.

Philip Pullman is frank about his ideological project, which is to take the grey world of Darwinist atheism and give it colour, grace and a framing myth. His (mostly excellent) collection of essays Daemon Voices (David Fickling, £20), includes one called The Republic of Heaven. He calls the Christian idea of the world – with God and a purpose – the Kingdom of Heaven, and compares it with the Republic of Heaven of the title, one in which God is dead. “A myth of the Republic of Heaven would explain”, he says, “how we came about, in terms that are true to… the facts of biology and physics and history… Our purpose is to increase the amount of consciousness in the universe… that purpose has a moral force.” His model is Paradise Lost, with the Fall of Adam and Eve a very good thing: he’s gunning for the concept of original sin.

So, how does his latest fit into all this? La Belle Sauvage is a cracking read. It’s set 11 years before the start of the earlier trilogy and it’s the most shameless wallowing in nostalgia for a vanished England I’ve encountered this side of the millennium. The hero is the son of the keeper of an inn called The Trout; the Oxford of the story is all Latin invocations, titled dons and Tokay drinking in the senior common room, rather like it was when the author, 71 this week, was there. On the bright side, there are nuns who are rather nice, as well as others who are repressive and cruel.

In this world, the Reformation hasn’t happened; the thought police are religious; the enemy is the Church. You know things are going wrong when schools have prayers before lessons and a woman resembling Rosa Klebb introduces the League of St Alexander, which encourages children to spy on their teachers and parents, as in Enver Hoxha’s Albania. She declares, after a prayer “in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ” that: “This is a Christian country in a Christian civilisation.” It’s meant to make our flesh creep, but is there anyone – anyone? – who actually thinks the real threat to free thought, liberal values and rational debate in our world is Catholicism?

Does it all work? There’s a quote from William Morris above the entrance to the Victoria & Albert museum, which declares: “The perfection of every art consists in the complete accomplishment of its purpose”. One of Philip Pullman’s objectives he accomplishes very well: he tells a good story, one with vigorous characters, baddies and goodies, and charming fantastical episodes and excellent English pub grub. It’s on the big stuff he fails. His alternative metaphysics are unintelligible – his contention that something called Dust embodies human consciousness is baffling – and his argument that the Church is the enemy of rational thought is odd given that Oxford came into being from scholastic activity organised by clerical institutions: the teaching began as a byproduct of ecclesiastical litigation[1. See The History of the University of Oxford, vol 1, ed. Jeremy Catto, 1984].

The problem goes deeper. One reason Philip Pullman’s story works, qua story, is that it is peopled with fantastical beings, river gods and fairies, but I’m not sure that Darwinian atheism really is hospitable to these creatures. They belong to God’s party, which includes angels and demons, things visible and invisible. Philip Pullman, a clergyman’s grandson, knows that perfectly well.