Credit: Richard B. Levine/PA Images

Some years ago I published a book about the Second World War[1. Michael Burleigh, Moral Combat: A History of World War Two (London 2010).]. The fact that I have not been a camp guard (or inmate), a commando, bomber pilot, or general was never important, any more than it is to Mary Beard, who is not ranked among Roman emperors.

I mention this by way of discussing businessmen entering politics. In keeping with a pervasive delusion of our time, only those with ‘experience of the real world’ should be in politics. Quite why ‘experience’ should then be reduced to that of the private sector is mysterious, for surely experience as a nurse, teacher, or on the dole or in jail, counts as ‘real’ too. In 2012, Mitt Romney even suggested that private sector business experience should become mandatory, though his background at Bain Capital downsizing workforces ultimately did not ensure his candidacy.

The election of Donald Trump and the resurgence of tycoon Silvio Berlusconi as the kingmaker of Italian politics obviously lend this subject topicality – as does the reverse case of someone like former German chancellor Gerhard Schröder, who has elicited much adverse comment for joining the board of EU sanctioned Rosneft, the Russian oil company. The examples of Tony Blair and Peter Mandelson spring readily to mind here, too.

When businessmen venture into politics, there are many potential conflicts of interest. The upper chamber of the Indian parliament, the Rayja Sabah, provides scandalous examples of big businessmen – all keen to slash red tape – who develop corrupt relations with civil servants and tamper with legislation to benefit their commercial interests, something their more sophisticated western equivalents do through paid lobbyists[2. See the interesting article by M. Rajshekhar “Why India has so many businessmen in parliament”, Quartz India, 23 March 2016. One might add that the lower house, the Lok Sabha, also has a large contingent of members avoiding charges of murder, rape and robbery through their parliamentary immunity.].

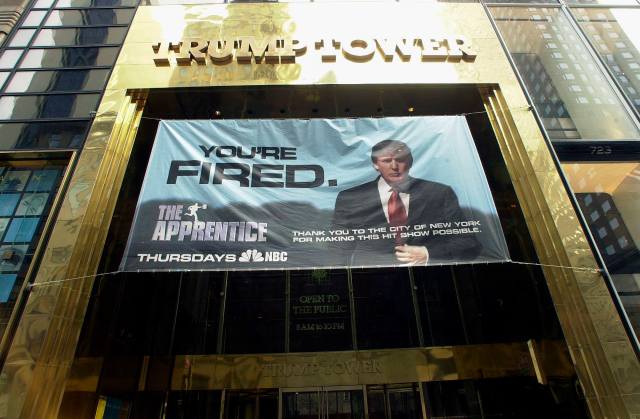

In reality, Berlusconi and Trump are so aberrant as to be untypical. One was convicted of tax fraud in 2013 (escaping jail in Italy because he is over 70), the other would have been fired long ago had he acted as a CEO of a public company as he has behaved as candidate and president[3. Lucy P. Marcus Time to judge Donald Trump as a CEO (Project Syndicate, 26 July 2017) makes this point about Trump from the perspective of a CEO.]. Both were property magnates who successfully parlayed celebrity into running for office. Berlusconi controlled large parts of TV media (and the newspaper Il Giornale), not to mention AC Milan, whose supporters club became the template for his party, Forza Italia. The casino and hotel-owning Trump used The Apprentice to transform himself into a global brand, which largely involves licensing his name on buildings[4. The best biographies of Trump are Michael D’Antonio, The Truth About Trump (New York, 2016) and David Cay Johnston, The Making of Donald Trump (New York, 2016). On Berlusconi see Paul Ginsborg, Silvio Berlusconi. Television, Power and Patronage (London, 2005). Berlusconi’s autobiography is called My Way.].

Most Americans or Italians were only familiar with their billionaire lifestyles through magazines and television. Apart from their success in building businesses empires, it would be impossible to confuse them with the bossy and sanctimonious professional middle classes, which was a plus point for many who voted for them. They like avoiding paying taxes, too, not to mention attending ‘bunga-bunga’ parties with girls called Ruby the Heartbreaker[5. Joan Williams ‘What So Many People Don’t Get About The US Working Class’, Harvard Business Review, 10 November 2016].

It is easy to understand why politicians like to adorn their administrations with big businessmen. They bring a certain can-do spirit to jaded cabinets and they are competent with figures and flow charts. The main appeal to the public is that businessmen appear to be ‘non-ideological’ outsiders and efficient managers, though from Enron to Lehman via Northern Rock and RBS there’s cause to doubt this. The lessons of the late banker-turned-MP Edward Du Cann in the 1970s, who messed up both Keyser Ullman and Lonrho before being declared bankrupt, are ignored.

In fact, businessmen are often highly ideological. After the Democrats routed the Republicans in the 1958 congressional elections, big corporations were horrified by the power of trade unions. In reaction, over a hundred corporations – including Alcoa, Kodak, Ford, Heinz and Hershey – sponsored their middling employees to become involved in local politics, while running their own civic affairs courses in house. Safe to say, none of the quarter of a million who took these courses were likely to support the Dems[6. Andrew Hacker, Joel Aberbach ‘Businessmen in Politics’, Law and Contemporary Problems, Volume 27 (1962) pp 266ff.].

Another conceit of our time is that ‘leadership’ is a transferable skill, as management books sold at airport newsstands glibly aver. What’s the difference between running a pizza chain and the NHS?

Most businessmen are corporate managers, whose autocratic inclinations about carpet colours, cars and logos, are often ill-suited to handling huge government bureaucracies subject to institutional checks and balances over which the big boss has no control. The entrepreneurial sub-tribe are supposed to be great dealmakers, as Trump never tires of saying. But as he has discovered, many political issues are more complex than negotiating the licence fee for sticking your name on a hotel in Azerbaijan or renegotiating mountains of corporate debt. Character and ability to communicate count, too. Rex Tillerson certainly had much real world experience as boss of ExxonMobil, but few would claim he has been as effective a Secretary of State as Henry Kissinger, or the Texan lawyer James Baker III (though admittedly George Schultz was a former Bechtel executive)[7. Timothy Egan, ‘The Wrong Résumé’ New York Times 31 May 2012.].

Fortunately, there are objective ways of testing whether businessmen who enter politics at the most exalted levels are any good at it. The US has had a scattering of presidents with business backgrounds, though the only one to achieve historic greatness was Harry Truman, a failed Kansas City haberdasher.

But Truman’s historic standing distorts the rankings of other presidents with a business background. Subtract Harry, and the likes of Calvin Coolidge (a banker), Herbert Hoover (a millionaire mining engineer), Warren Harding (newspaper magnate) and George HW Bush (an oilman) all figure in the bottom third of the rankings drawn up by the American Association of Political Science[8. William Campbell, ‘Businessmen, including Donald Trump, make bad presidents’, The Hill, 30 September 2016 for these surveys.].

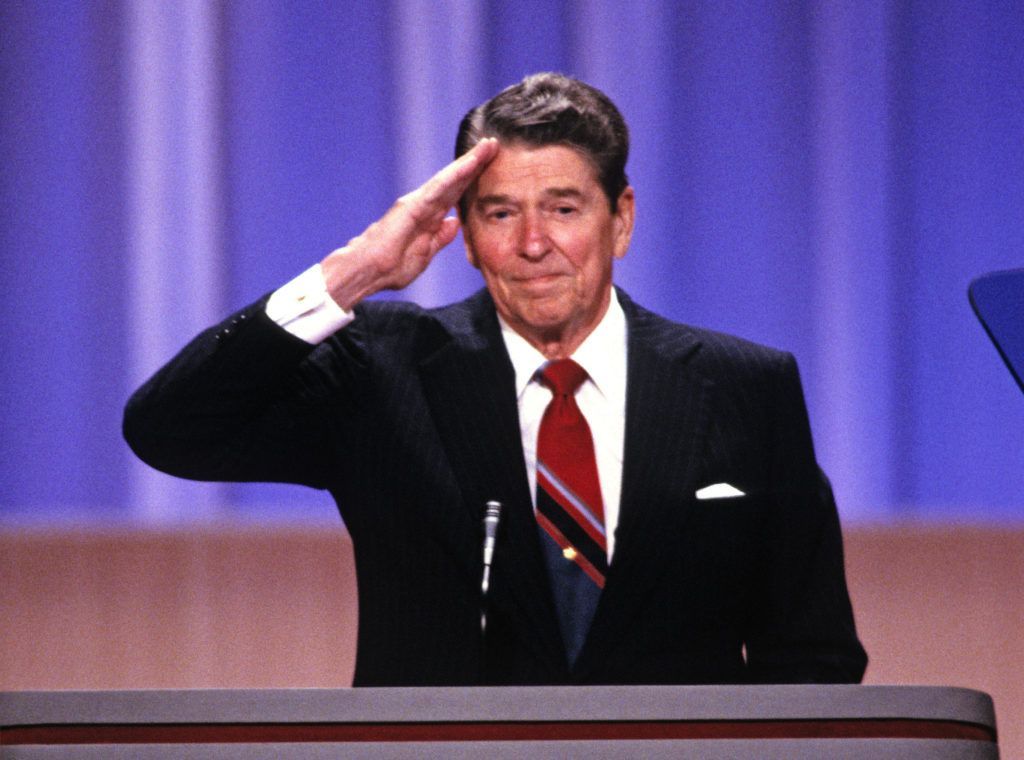

By contrast, career politicians such as FDR, JFK, LBJ, Clinton and Obama register much higher, as do a wartime commander (Eisenhower), a Princeton professor (Wilson) and an actor, General Electric motivational speaker and union organiser (Reagan). Even though Clinton and Obama could not read a balance sheet, they created millions of jobs while in office. Speaking of ‘real world experience’, the polio-stricken FDR once movingly remarked that after spending two years just trying to wiggle his toes, anything else seemed easy.

Most businessmen who enter politics are greyer than the lurid examples I began with. Billionaire Michael Bloomberg was a fine Mayor of New York, and he would have made a decent Republican president. In this country, some top businessmen have found politics a rougher trade than they imagined, for example Archie Norman, Digby Jones or Jim O’Neill. But many businessmen have successfully made the transition, like former bankers Philip Hammond and Sajid Javid or the millionaire publishers Michael Heseltine and Jeremy Hunt, who have been very effective ministers[9. Larry Elliott, ‘Jim O’Neill is just the latest business leader to have his fill of politics’ The Guardian, 23 September 2016.].

While having been in business is no impediment to the highest office — for businessmen can be public-spirited too — it bears no correlation with how decorously or effectively a politician conducts himself. It’s a fad, nothing more than that, and the Trump presidency may see it pass, terminally.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe