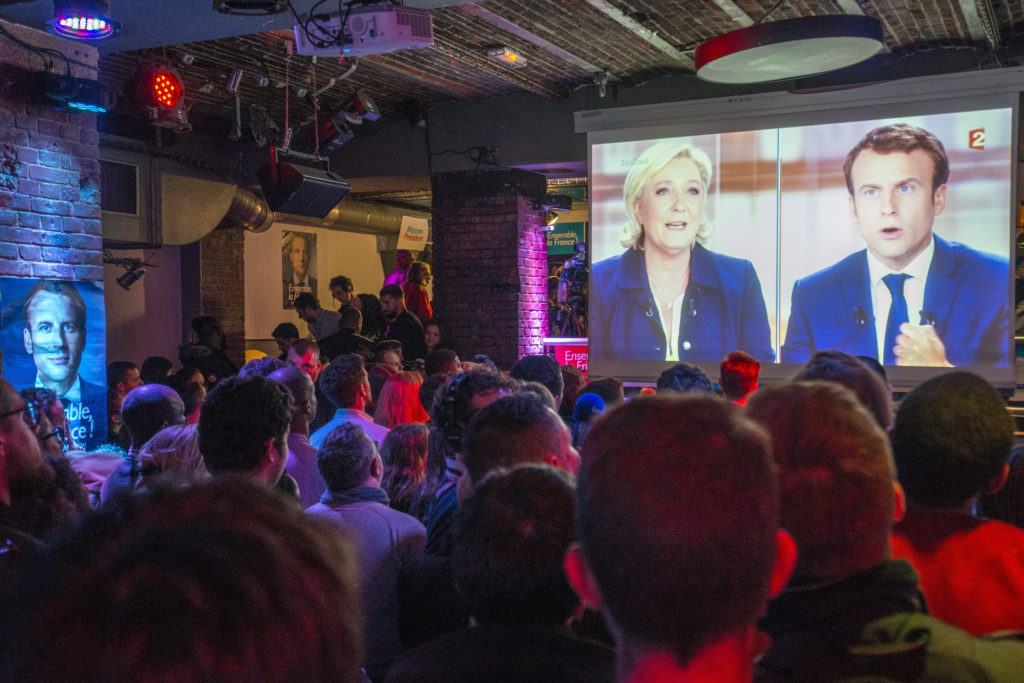

Christian Liewig/ABACAPRESS.COM/PA Images

Last month President Emmanuel Macron addressed a largely student audience at the Sorbonne, elaborating his dream for Europe. He was better in the animated Q&A[1. Discours d’Emmanuel Macron à la Sorbonne: quel avenir pour l’Europe (YouTube 26 September 2017) for a recording of his speech.].

The venue was important. The auditorium was where in 1992 François Mitterrand trounced the Gaullist Philippe Séguin in a live TV debate about the Maastricht Treaty. Ironically, most of what Macron had to say involved fixing flaws that ensued from it, including the democratic deficit, the Euro, and the Schengen Agreement[2. Fabrice Pothier Macron’s European vision, IISS blog, 16 October 2017.].

The timing was significant too. Delivered a day after the German election, Macron was signalling that “the time when France proposes is back”; in other words, under Macron France would no longer be a semi-functioning and subsidiary component in the Franco-German ‘engine’ within Europe. Appointing a cabinet whose main second language is German was one signal of intent.

It was also striking that Macron distinguished between ‘Europe’ and institutions elaborated by bureaucrats and lawyers, which – as he later told German journalists – “aren’t particularly important to me”. His proposal to slim down the Commission to 15 members, even if it meant France giving up portfolios, will have shocked Jean-Claude Juncker. So will Macron’s enthusiasm for a two-speed EU in which the vanguard ‘core’ will forge ahead, exerting a gravitational pull on others to join the common ambition. Antonio Tajani, the Italian President of the European Parliament, is probably having nightmares about Macron’s desire for a separate Eurozone parliament[3. Klaus Brinkbäumer et al ‘Interview with Emmanuel Macron’, Spiegel Online, 13 October 2017.].

It is doubtful whether, contrary to the President’s intention, Macron’s speech will inspire many young people to be passionate about an EU, artfully conflated with a continent, whose ostensible raison d’être of maintaining peace seems nostalgic, a kind of rote confession of faith emptied of meaning. This was doubly so as the speech meandered into details of policies which the EU has long subscribed to, such as a common border agency (Frontex is 12 years old), deeper involvement in Africa, and the promotion of bilingualism.

Nonetheless, Macron did make a coherent case for Europe as an amplifier of national sovereignty in an age of economic superpowers, though it seems doubtful whether he will have persuaded many on the Eurosceptic populist left or right, not least in France itself. His image of a sovereign hand concealed by a European glove is not new (Weimar Germany tried it under Gustav Stresemann in the mid-1920s) and may be too sophisticated for audiences with more robustly nationalist passions, many of whom also view the EU as a disabler of local democratic control in an age of globalised capitalism. Rather than pandering to populist fears Macron issued an explicit challenge, confident that, in France at least, the Front National has collapsed beneath its internal divisions.

The speech also had to be mindful of German sensitivities, which have increased because the liberal FDP will be a key element in Angela Merkel’s new four-way Jamaica coalition. Since Macron’s election, the German line has been a sequential one, insisting that France tackle its own structural problems with a local version of Germany’s Hartz IV labour market reforms, before substantial reform can be ventured on a European level[4. In reality, relations between Macron and the FDP’s Christian Lindner are very good (the later campaigned for the former) and En Marche has joined the FDP in the ALDE block in the EU parliament. See Michaela Wiegel ‘Zwischen Albtraum und Wirklichkeit’ FAZ, 18 September 2017.].

This is why Macron was tentative in advocating a common Eurozone budget. His main trade-off was an offer to reconsider the Common Agriculture Policy in return for using (harmonised) corporation tax receipts to create a common fund. The aim is to reassure German taxpayers that they would not be on the hook for liabilities racked up by their profligate southern neighbours.

Macron emphasised one area that Germany and others could buy into in the era of Putin and Trump: enhanced co-ordination of European defence and security policy, including R&D and arms manufacturing. Absent the British and that is much easier to achieve, especially if the emphasis on development and conflict preclusion and resolution does not clash with Nato’s role. But much of what Macron proposed already exists: a few Dutch-German and Franco-German combined forces and the integration of firms producing tanks, for example. Whether they can agree a common EU defence strategy, and whether the Germans will sign up to the much more interventionist stance Macron is proposing, seems extremely dubious[5. ‘Deutsche Verteidigungspolitik setzt auf EU’, DW, 10 November 2016 for the pre-existing trend which Trump’s election has accelerated.].

Elaborating visionary dreams for Europe is probably a relief from governing a surly France. In a revealing interview, Macron blamed post-modernism for subverting ‘all grand narratives’, thereby making it almost impossible for leaders to practise what he calls ‘political heroism’. Behind the steely Rothschilds banker is the student of literature and philosophy (before Sciences Po and Ecole national d’administration) who is well read in French and German literature (Michel Houellebecq is a favourite) and plays Bach and Mozart for relaxation[6. Brinkbäumer et al ‘Interview with Emmanuel Macron’. At the Frankfurt Book Fair this month, Houellebecq repaid the compliment, saying: “But now that Emmanuel Macron is in office, there is hope for the country’s national pride. He said he felt things had changed with Macron’s election win, and that he hopes the French will recoup their national pride, as well as their arrogance — with the latter certainly carrying a positive connotation.” See ‘French author Michel Houellebecq in Frankfurt Book Fair’s Spotlight’ Deutsche, Welle, 12 October 2017.].

So far, Macron has been lucky in his populist opponents. During the TV debates before the election Marine Le Pen demonstrated she was unfit to be president, having unfortunately subordinated her party to a campaign all about her. She has also been part of the political furniture for a long time and so found it hard to pose as an ‘outsider’. The left is split between a sclerotic socialist party and supporters of Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the firebrand leader of France Unbound. His wild claims include the idea that the “grumbling Germans” regard the EU as a vehicle for empire, or that Le Monde journalists are “CIA spies”[7. Amandine Réaux ‘Jean-Luc Mélenchon s’en prend personnellement à deux journalists du Monde qu’il accuse d’être influencés par la CIA’, Le Lab politique Europe, 15 November 2016.]. Some non-Communist trade unions disagree with Macron about the process and speed of structural reforms, rather than the necessity for them, in a country whose malaise is proverbial. The promised hot autumn on the streets has so far been a desultory affair unlikely to make Macron shy away from reform as did Hollande, Sarkozy and Chirac.

Macron’s main problem, judging by his wilting polling numbers, is his autocratic manner, for he does not have de Gaulle or Mitterrand’s background to get away with it. Being president is different from orchestrating a political start-up movement of the liberal centre, though Macron was extremely skilful in mimicking Europe’s other insurgencies. He seemed to come out of nowhere, though in reality he is deeply connected to an array of elites who have sped him on his way[8. François Denord, Paul Lagneau-Ymonet ‘New man Maxcron’s old-style expertise’, Le Monde diplomatique (March 2017).].

While one can see the point of publicly reminding Putin and Trump that France is a major power, there is a gap between the rather slight President and the aloof, ‘Jupiterian’ figure he likes to project. It does not help that he regards most journalists with ill-concealed contempt. A first TV interview as president consisted in him talking, for a long time[9. Pauline Bock ‘Emmanuel Macron’s first TV interview shows why he avoided it for so long’, New Statesman, 16 October 2017.].

While attacks on self-interested elites are ten a penny nowadays by those often sanguine about a developing ‘mobocracy’, Macron is probably wrong to lash out at “slackers and cynics” who are frustrating his domestic reforms[10. Nicholas Ventour ‘Emmanuel Macron’s arrogance problem’, Politico.eu, 20 September 2017.]. He claims he was referring to professional agitators defending entrenched interests but they do not sit well with simultaneously cutting housing allowances and wealth taxes. Reasonably he claims that it is not him “distributing the money, but other future generations”. The answer to blue-collar gripes are continued education and vocational training rather than taxes, which simply encourage entrepreneurs to flee. “Envy”, says the President, “paralyses our country.”[11. See Jonathan Fenby ” ‘Jupiter’ or just another politician?’, The Guardian, 30 July 2017 is excellent on the obstacle of conservative forces Macron faces.]

Whether Macron can sustain the momentum he needs to swiftly ram through domestic reform, often using decrees to do so, while also tackling the forces of inertia within the EU is moot, not least because he seems a figure from before the 2008 crash, a French Blairite in fact, rather than a man able to read what he calls the Zeitgeist. He also knows that the neophyte En Marche may be a mile wide, but it is also an inch deep, and nowadays majorities can melt like snow.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe