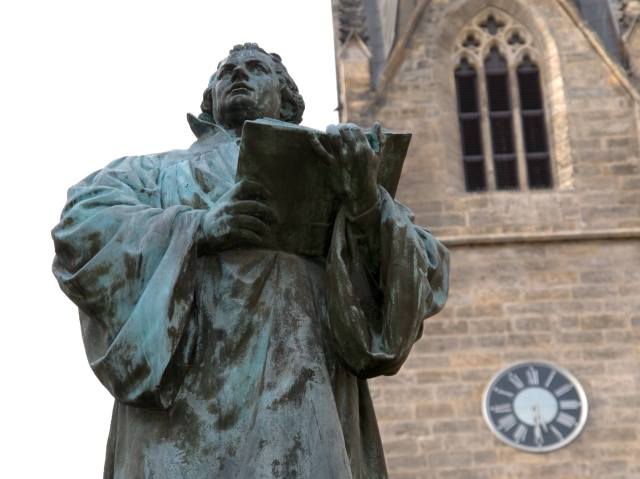

2017 sees the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther’s protest against the medieval church’s practise of Indulgences, an event which led to the Reformation — a radical and lasting restructuring of European life and politics. 2017 also sees the first anniversary of our decision to leave the EU, an event which could do the same. What might the events of 500 years ago have to say as we also enter this period of uncertainty in the life of Europe?

The Reformation was more than a religious event. It was a transnational movement to address a number of urgent social issues in sixteenth century Europe which are uncannily similar to ones we face today.

We have more in common with that era than might be obvious. People living in 1500 had just experienced a massive information revolution. The invention of printing had replaced a laborious method of reproducing documents by hand with one that enabled the rapid dissemination of information. Between 1450 and 1500, eight million books were published — more than the scribes of Europe had managed in all the centuries before them. The past fifty years have also seen a seismic change, with the internet and social media radically changing the way we communicate. Just as anyone can set up a website, or Twitter feed, so in 1500, almost anyone could set up a printing press, gather sermons, and spread them around Europe within weeks. The printing press opened the door to the proliferation of ‘fake news’ – documents pirated without permission from authors, or spreading false rumours like wildfire, leading to uncertainty on who to believe. No longer did the emperor or the church have a monopoly on information or opinion.

Furthermore, in 1517, the structures of medieval society were already crumbling. The rise of Renaissance culture, along with the emergence of large international banking, houses gave birth to new wealthy urban elites marked by their ostentatious learning, patronage of the arts and politics. The result was an erosion of old structures and certainties, especially for those lower down the social order, who felt left out of these changing social arrangements. Much like today, value and worth seemed increasingly measured by income or education, achievement or visible success. This early capitalism freed the individual from the bondage of economic and social ties, but also began to erode the security given by those ties.

The theology of the time didn’t help. Some strands of late medieval preaching suggested that God helped those who help themselves – that he rewarded those who managed to achieve a level of observable piety, who try hard to be good. Luther’s message that we are justified not by what we do or achieve, but by the grace of God appealed to people left isolated in the rat race of the emerging modern world. As Luther himself put it: “Sinners are not loved because they are attractive, they become attractive because they are loved.” This message gave security, a sense of value, worth and freedom to those who felt abandoned and insecure in a fast changing world.

These social developments also led to extremes of poverty and wealth much like today, with income inequality and resulting economic migration. Every city had its army of beggars — some mendicant monks, others left behind in the new capitalist world, still others migrants from regions caught in the upheaval of conflict. And again, the theology didn’t always help. Giving alms to the poor could contribute towards gaining the spiritual merit that led to salvation, so in an odd circular logic, the existence of the poor seemed necessary for the salvation of the rich.

Luther’s doctrine changed this. Salvation was no longer gained by acquiring merit through performing good works, but simply by faith. Almsgiving was detached from personal salvation. The Reformers urged that money formerly spent on indulgences, masses for the dead, and pilgrimages should now be spent on poor relief. As a result, a serious attempt could be made to eradicate poverty. Reformation cities often banned begging as a demeaning way of addressing destitution, and instead poor relief schemes were set up, using the church-based common chest for contributions. In Geneva under John Calvin, deacons were appointed specifically to administer funds for the poor, charging excessive interest was condemned, convents were turned into to hospitals, and monasteries into schools for the young, in what was effectively the first comprehensive education system in Europe.

This was an era that also saw a revolt against the elites. Like the way many people see Brussels today, the distant power of Rome levying taxation and issuing legal decrees seemed a long way from the realities of life in much of Europe, and the new urban banking class offering loans at exorbitant interest was often resented. Luther harnessed this popular sense of resentment. He was a gifted composer, writing simple hymns and poems in bare, simple language. In 1521, he started his translation of the Bible into German. Unlike the later King James Version, he wasn’t worried about word-for-word exactness. He wanted the prophets to speak ordinary German: “We must inquire about this of the mother in the home, the children on the street, the common man in the market place. We must be guided by their language, the way they speak, and do our translating accordingly.”

Luther would have been brilliant on Twitter, with a keen eye for the snappy, memorable slogan like “faith alone” or “a Christian is a perfectly free lord of all, subject to none.” He was a master of the soundbite, the carefully crafted insult, the popular tract that appealed over the heads of the intellectual or moneyed elite to tap into the frustration and feeling of alienation that many people felt.

The other big factor that shaped early sixteenth century Europe was the growth of Islam. In 1526, Ottoman Turkish armies had beaten the forces of the king of Hungary at the battle of Mohacs. In 1529, they stood at the gates of Vienna, and many, Luther included, were convinced Europe was about to become Muslim. This naturally caused fear and panic among Europeans for whom the Turks were exotic but strange enemies. What is remarkable about the Reformers’ response to the spread of Islam is that they did not generally resort to Islamophobia, but aimed instead at a renewal of the wellsprings of their own Christian faith. Luther saw the rise of Islam in medieval Europe as a call to Christians to pray, to repent, to read Scripture more deeply, to recover the good news of the grace of God, and to develop a more disciplined Christian life. Luther wrote a fair bit about Islam, helping sponsor a translation of the Quran into Latin, so it could be better understood (and refuted of course) and expressing a certain degree of admiration for Muslim piety and fervour, in comparison to what he saw as the comparative flabbiness of European Christianity. Henry VIII may have dissolved the monasteries, but Thomas Cranmer’s aim in composing the Book of Common Prayer was not so much to eradicate monastic discipline, but to make it possible for ordinary Christians. Even if they couldn’t say all the monastic services, they could at least say morning and evening prayer each day.

A search for personal value, the gap between rich and poor, revolts against the elites and the attraction and fear of Islam — they all sound very familiar to us. We too live in a competitive age that leads to success for some but despair for others. Disparities between rich and poor have led to at least part of the migrant crisis as others seek their share of western wealth, and the growth of foodbanks and harsh poverty in many of our cities. Brexit and the rise of Donald Trump were both in part revolts of those who felt left out of the prevailing winds of culture and economics. And Islam struggles to find its place in western societies, leading to admiration for some and fear for others.

The Reformation had its deep flaws, often derived from the failings of its leaders. Yet it was a remarkable attempt to meet these challenges which early modern Europe faced through a message of personal worth, an assault on poverty, a feeling for the disenchantment of many and the renewal of a disciplined life. If the European Union’s vision has stalled, with the Brexit negotiations on the horizon, the question for our new government is not just whether it can arrange an orderly withdrawal from the EU. It is a much bigger question – can it provide a new vision, powerful enough to re-shape modern Europe? Can a vision be found that avoids the divisions brought about by the Reformation, yet mimics its motivating power to give a new sense of personal value and find new ways to create a sense of a common bond in society? Only time will tell.