The-Vagabond, Getty Images

Gill Bennett was Chief Historian of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office from 1995 to 2005.

More than a century has passed since the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia in 1917; seventy years since the end of the Second World War; twenty-five since the end of the Cold War; yet arguments continue as to which form of political extremism, communism or fascism, has been responsible for a greater number of deaths.

The numbers themselves are disputed, muddied by distinctions between deaths in war and peace, between military and civilians, between those killed and those who died as a result of disease, famine or forced migration. Since the idea of mass murder is both sensational and shocking, media coverage inclines to big numbers and broad accusations[1. See, for example, the blog by John J. Walters: ‘Communism killed 94m in the 20th Century. Feels Need to Kill Again’, March 2013; Chairman Mao was the ‘greatest mass murderer in history’, The Daily Mail, 7 October 2014.]. Often the numbers are so large it is hard for an individual to process or relate them to events. Generations with no personal or family memory of global war can find it particularly hard to put these statistics into context[2. See The Independent, 17 October 2016: ‘Millennials believe George W. Bush killed more people than Stalin’.].

Some argue that while the crimes perpetrated under fascism, especially in the form of National Socialism (Nazism) under Adolf Hitler, have been documented in detail, the same attention has not been given to crimes committed under communism. This argument can lead to a sterile wrangle over doubtful numbers, and may not be the most helpful way of comparing crimes attributed to fascism or communism. As Timothy Snyder wrote in his thoughtful analysis ‘Hitler vs Stalin: Who Killed More?’ the question raises issues of quality as well as quantity, and is much more complex than it may seem[3. Timothy Snyder, ‘Hitler vs Stalin: Who Killed More?’ in the New York Review of Books, 10 March 2011.]. It is more illuminating to consider why murders committed by the extreme left or right tend to be talked and written about differently.

Thinking about the past: continuity and change

In the early 21st century it is more common for certain ideological assumptions to be rejected by a majority of people in democratic societies, than it is for them to be widely accepted. Both in Europe and the USA, for example, the idea of glorifying Nazi ideas of racial purity, with their evocation of the Holocaust, provokes widespread abhorrence. Even though Nazism was discredited with Hitler’s death in 1945, it retains the capacity to inspire rejection and inflame passions, and the equation of fascism with mass murder is potent. There have been many examples of post-war ethnic cleansing and genocide, from the Balkans to the Middle East to Rwanda. Though the causes of these terrible episodes are complex, the perception of a link with the Holocaust remains in the minds of many onlookers, even if not in the minds of those most closely involved. Similarly, the rise of right-wing nationalist or populist parties in supposedly democratic states causes unease and apprehension, and even if they achieve power they are very unlikely to call themselves fascists, let alone Nazis.

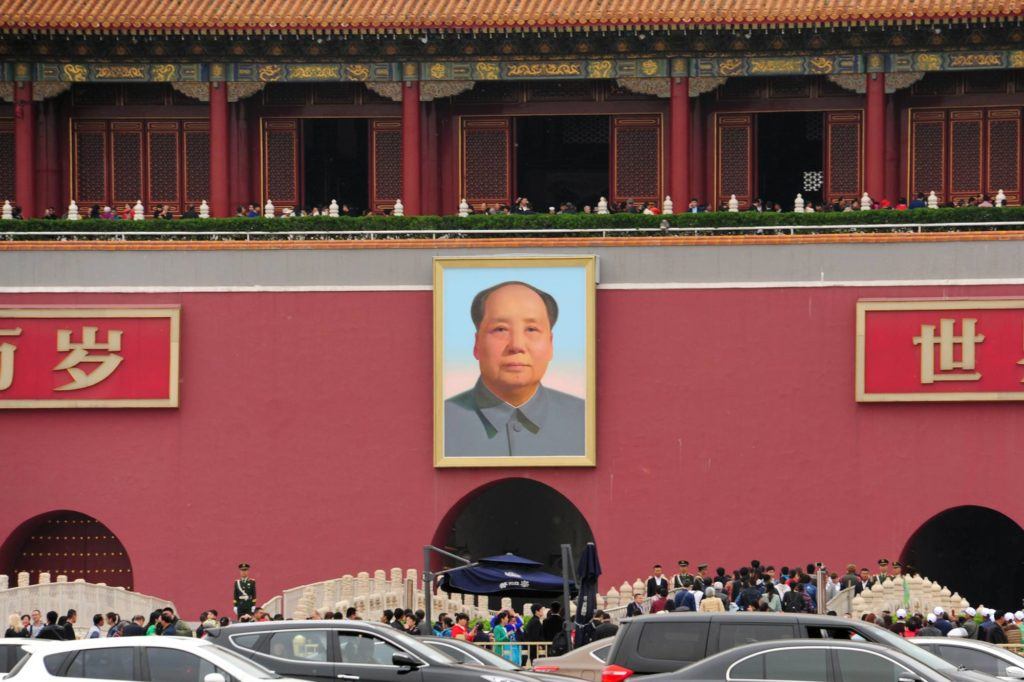

By contrast, the ideology, or perhaps more accurately the ideals, of communism retain the capacity for positive inspiration. This is most obviously true in Communist regimes like the People’s Republic of China, formed in 1949. Although the Soviet Union is widely thought of as the prototype of communist rule, the Chinese revolution was more ambitious and enduring than its Soviet counterpart, and more people lived – and still live – under communist states in East Asia than they ever did in post-war Europe.[4. See Stephen Smith, Introduction to The Oxford Handbook on the History of Communism (Oxford University Press, 2014).] In the Soviet Union, Stalin’s economic policies, purges and deliberate terror campaigns between 1923 and 1953 led to millions of deaths (the numbers are disputed). During the Great Leap Forward under Mao Zedong from 1958 to 1962, an estimated 45 million people perished in China from starvation or overwork; in Cambodia, over 20% of the population were killed or died under the Khmer Rouge in the 1970s.

Such crimes are not unreported: for example, The Black Book of Communism, published in 2006, set out in detail ‘crimes, terror and repression’ across the globe[5. S. Courtois, N. Werth et al, The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression (Harvard University Press, 2006). Many detailed rebuttals can be found online, questioning elements in this work.]. Most people in non-communist states are aware that communism, as well as fascism, has been responsible for millions of deaths. Despite this, many people, not just in communist regimes but also in Western democracies, admire and are inspired by communist ideology, or at least by extreme left-wing ideals such as public ownership of the means of production and the redistribution of wealth. In a context of global financial and political instability, both left- and right-wing extreme views can seem attractive, but as a general rule those of the right seem more alarming to the majority of people than those of the left.

Looking back in order to look forwards

Admiring communism does not, of course, mean condoning mass murder, but it may mean talking about it in different terms. While fascism glorified war and violence for its own sake, Marxist theory saw force as the midwife of history – a means to an end. As the archives of former communist countries have become available since the end of the Cold War, it has become clear that however repressive those regimes may have been, many of their leaders continued to believe that they were building a better world. This idea of seeking to improve lives is key to understanding the different perceptions of the crimes committed by fascist, or communist regimes.

Hitler thought he was building a better world, too, based on Aryan supremacy and the elimination of ‘inferior’ elements. Those expressing such a view now face horrified opposition, even from the right. But a far greater number of people are attracted by the kind of ideals on which communism is based, however badly their implementation turned out in practice. Some argue that this means extreme left regimes are allowed to get away with murder, since those on the political left wing are reluctant to criticise them. But it is important to avoid the dangers of Historical Attention Span Deficit Disorder, a phrase coined by the intelligence historian Professor Christopher Andrew: it means we must be careful to compare our current assessment of past events with what was, or could have been known about them at the time.

Media reporting of atrocities, civil wars or natural disasters can have a numbing effect, giving the impression that the world is in a worse state than ever before. But as every historian knows, in any given period many people live through terrible events without realising their full horror; while at the same time they feel that conditions – political, economic and international – are worse than in the past and deteriorating, even when the facts show otherwise. Understanding this helps to keep a grip on reality when judging what is known about crimes committed in the name of political ideology, rather than what is assumed to be true.