Charles Dickens' Dream, painted by the author's grandson in 1931.

During our examination of the state of western capitalism, UnHerd has confirmed through a major transatlantic poll that the public makes clear distinctions between a deserving rich – including inventors and manufacturers – and an undeserving rich – including bankers, CEOs and property investors. The idea of a deserving and undeserving rich was promoted by Michael Gove at a Legatum Institute event in October 2015 and leans on the idea of a deserving and undeserving poor. Today, Michael Burleigh revisits the term’s history.

***

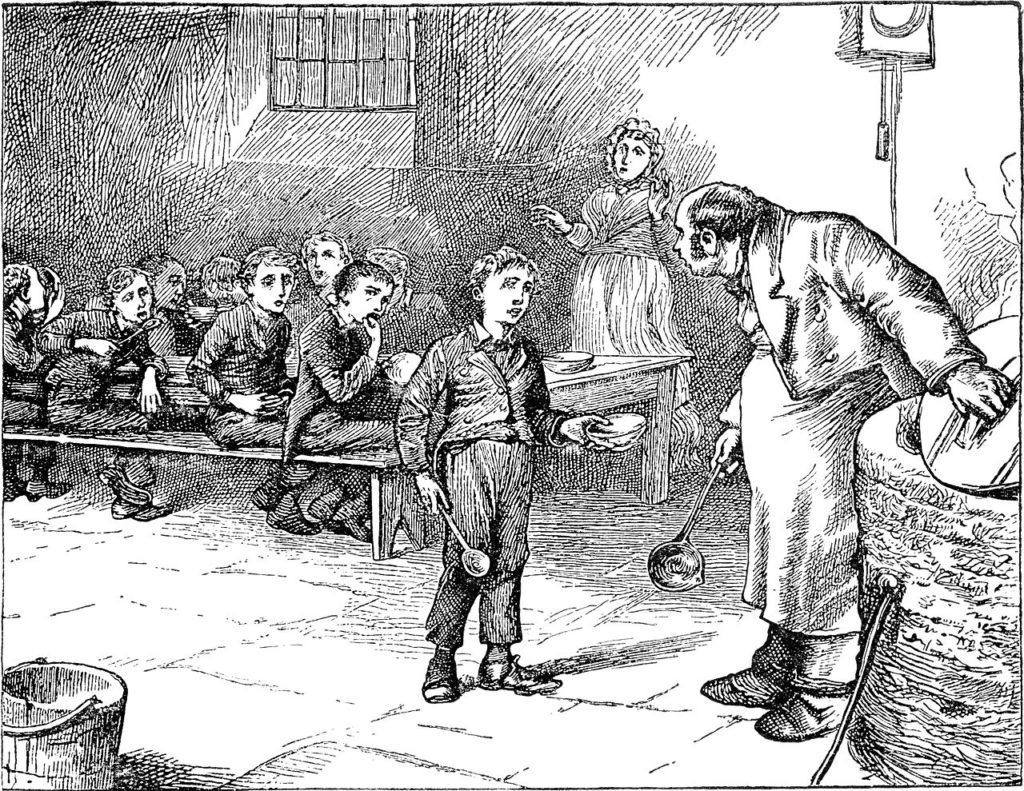

The distinction between a deserving and undeserving poor is more venerable than many imagine, and it remains a contemporary one. A feckless and fecund ‘underclass’, binging on junk food, junk TV, drink or drugs is often juxtaposed –not least in the junk media – against the respectable working class.

In the Middle Ages, poverty was not regarded as a vice provided one bore it meekly, and voluntary poverty like that of the Franciscans was the apogee of virtue. Parasitic idleness was seen as the gateway to crime, though ‘avarice’ or material greed, a vice of the rich, was a much greater sin because it was seen as a form of spiritual lassitude.

The idea that the poor can be categorised in terms of moral failings was an Elizabethan rather than a Victorian one, though in this area as in that of butterflies and moths, their contribution was scientising and taxonomic.

The dissolution of the monasteries between 1536 and 1540 eradicated one of main refuges for the poor, while swelling their ranks by rendering monks and nuns homeless. Land enclosure to raise sheep created bigger farms requiring fewer labourers, while the poor lost customary rights to fish, fowl and fuel. A 25% population increase during the Elizabethan era, a series of poor harvests, and an increase in what we would call ‘drifters’, prompted Elizabethan governments to legislate a series of Poor Laws between 1563 and 1601. The 1601 Poor Law formed the template for legislation in this field until the 1834 Poor Law Reform Act.

The Elizabethans established mechanisms for dealing with the poor, partly because they feared civil unrest. Justices of the peace assessed local needs and then made the rich pay a tax which in 1598 came to be called the rates. Centrally issued Books of Orders instructed JPs how to deal with outbreaks of dearth or disease.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe“the Germans have almost too many ventilators and testing facilities, tax-funded precautionary capacity that now looks more prudent than wasteful.” For the record, Germany doesn’t have a tax-funded nationalised health system, but is funded by numerous ‘sickness funds’ and private health insurance, although many hospitals are municipal (as indeed they were in the UK prior to the NHS), while some are university-based. If it were up to me, I’d abandon our system and adopt that of Germany, but am resigned to that never becoming acceptable to the electorate while it is so useful to opponents of the Conservative party during elections.

There is also an opportunity for a much better system to evolve where more power, with funding attached, is devolved more locally and then those more local communities link up in associations of common interest. We have the technology for those associations of common interest over many common issues to not be limited by distance. A massive extension of the concept of town twining with similar towns in other nations.

Probably won’t happen, but the idea has merit. Covid is causing many old preconceived ideas to be challenged and some of the more productive solutions that have been found to the challenges we have faced could lead the way to solutions to other challenges. If the EU, as an institution, crumbles more rapidly as a result of Covid, then that would be a massive positive to come out of this mess in my view.

Marshall writes that Kosovo “is discussing land swaps with Serbia, which, if implemented, could enflame irredentism elsewhere.” There is only one land swap that seems to be under active discussion, as far as I know, that would have Kosovo trading the Serb-majority Kosovo Mitrovica region in northern Kosovo for the Albanian-majority Presevo Valley region of Serbia. One may ask why, if redrawing the borders of Kosovo is considered a good thing now, it was not considered a good thing in 1999 when NATO occupied Kosovo, then a province of Serbia. The mantra “Borders are borders” hardly applies, since they were violating Serbia’s borders. If they thought it made better sense to have the 40,000 Serbs in Kosovo Mitrovica (about a third of the ethnic Serbs remaining in Kosovo) be governed from Belgrade rather than PriÅ¡tina, why wasn’t that stated at any time between 1999 and Kosovo’s unilateral declaration of independence in 2008? Why is this coming up only now in the context of a land swap? Redrawing the borders of Kosovo raises other issues besides ethnic makeup. Kosovo Polje, the site of the Battle of Kosovo in 1389, and the cathedral at Peć, both in northern Kosovo, should really remain part of Serbia. Asking Serbia to give them up is like asking England to give up the site of the Battle of Hastings and Canterbury cathedral. The NATO leaders never seriously considered redrawing the borders in this way, and now, unfortunately, it is probably too late.

Politicians have always, and for some understandable reasons, resisted hypothecation of taxes. From Colonel X who would happily pay for security but not for social security, to the committed childless who would stump up for enhanced social care for the over 70’s but not for childcare for the under 7’s, it would create nightmares. But in this nervous new world, a bold administration might abolish National Insurance and replace it (and some income tax) with a health insurance scheme, an unemployment insurance scheme, and a pension guarantee scheme. That would bring home the cost of these essentials. No denial of cover to anybody, the government pays for those who can’t find the cash.

I have some sympathy with people who trade through a company, and pay themselves the minimum salary necessary to obtain full entitlement to state pensions while paying zero NI, and pay themselves with a dividend, but in this situation, they are being handed the microphone solely to add to the media’s search for stories to undermine the government. HMRC have disliked it for a long time, considering it to be ‘disguised remuneration’, and everyone knows that although the practice is common dodge and legal, it is a tax-dodging ruse denied to most of us, and what’s more, if the Chancellor were to find a ‘cure’ for it, it might open up even more chances for unscrupulous people to take advantage of the current situation to defraud the rest of us.

“The story of civilisation is one of drawing upon this instinct in order to cooperate and share resources at an ever-higher level ” from family to tribe, from tribe to nation. But can we go higher still ” from nation to regional union and even to truly global governance?” This claim is surely an oversimplification; both it and the question that follows imply a neat model undermined by the complexities of actual historical development.

In many parts of the world regional unions preceded nation states. The tribes were incorporated into an empire (a “regional union”), which subsequently (much later in many cases) broke down into nation states. As late as the nineteenth century, virtually all of Eastern Europe was under imperial writ (Habsburg, Russian or Ottoman), and the empires were all ethnically, linguistically and religiously diverse. Of course, the imperial authorities often delegated to local monarchs and chieftains, but the relevant territorial sub-units weren’t themselves especially logical in terms of “tribal” self-determination; thus, ethnic Germans with the same language and the same religion found themselves scattered among numerous separate principalities under the nominal authority of the Holy Roman Empire, as well is in many eastern cities beyond it.

In most cases, the disarticulation of imperial structures and subsequent process of national self-determination involved a deliberate attempt to create “tribal” feeling, either from above (consider the way in which “standard” Tuscan was imposed on speakers of everything from Friulian to Sicilian once the Kingdom of Italy came into being), or through the self-conscious activity of intellectuals (think of Finland, where the educated class, largely Swedish-speaking, made a deliberate effort to learn and adopt the Finnish language, Finnish names, etc). Consider also that at least some of these new nations cemented their tribal identity via mandatory population exchanges in a deliberate attempt to create homogeneity (that between Greece and Turkey in the 1920s being the most obvious example).

The EU is often regarded as a kind of postmodern, ahistorical structure. But I have often thought that it resembles nothing so much as an attempt to rebuild the liberal autocracy of the Habsburgs. Consider too that modern China, India and Russia, all vast and all ethnically and linguistically diverse, bear a much greater resemblance to the historic European empires than they do to modern nation states like, say, Portugal or the Czech Republic. The imperial model is still with us.

I’d add that in the middle ages most Europeans would probably have regarded themselves first and foremost not as members of their tribe, nor as subjects of their king, nor as inhabitants of a geographical territory – but as members of the Church and citizens of Christendom.

I’m 68. Grew up in a small town, where having a water heater was a luxury, a washing machine, if you could have it, was a TREASURE to be kept, unless you really enjoyed hand washing all you clothing, towels, and bed sheets. A dryer? Yeah, right. Line hanging was all you had. And, if “Mother Nature” gave you a sudden rain gift, drying was extended until… . Air conditioning? Don’t make me laugh. Ok, I just did.

Hair dryer? Towel dry, comb or brush to taste, and air dry.

The kind of food you had access to was all dependent on the Seasons. There wasn’t such a thing as year round availability of all vegetables and fruits. You had to wait for harvest. The only things you could “really” count on was eggs and milk, IF you happened to have a dairy farm, or a livestock farm nearby your town, or you grew chickens and had at least a cow. Did I forget to mention that growing your own livestock means you also have to deal with disposing of their excrement?

If you had decent electricity supply, black outs were to be expected every now and then. It was par for the course. Anyway, you always had the “for sure” back up of candles.

Did I mention you had to be prepared to have some dry food always ready, in case there were extended black outs, and you didn’t have ways or the space to make a fire and cook with it.

The most common ways of personal transportation? You walked, horse, horse pulled cart, bike, for hire transportation, or the ultimate luxury: your own car. By the way, there was no such thing as “leasing”.

Entertainment? Mostly go out and play. Come back when the street lights come on.

TV? If available, only B/W with only 4 channels MAX, for a few hours a day. Telephone service? It was all manual connections, and there wasn’t such a thing as “unlimited use”. EVERY MINUTE was timed and charged for. Long distance was charged a higher rate. Texting, Messenger? The common tool for those was called: Writing a letter. You put pen, or pencil to paper, wrote, folded said paper, put it in something called an envelope, sealed envelope, wrote your name and address on the upper left corner, and the recipients’ address in the center of said envelope. Finally, you went to the Post Office, bought s stamp and had it mailed. Then…kept living you life and wait for any response, if any. Many times the said letter got “lost in the mail”.

Pictures? Only film, and you had to send it out for it to get developed and printed. You were charged even for bad prints.

Personal computers, Internet, WiFi? You kidding, right?

Oh…how much I don’t miss those enchanting days!

Climate change isn’t raging. Where is that happening?

We should fear a colder climate, not a warmer one. Life has always done very well in warmer times.

[…] during the early stages of capitalism, narratives were created about an “undeserving poor”: people, now landless, who refused to do what the new capitalist class wanted them to do, namely to […]