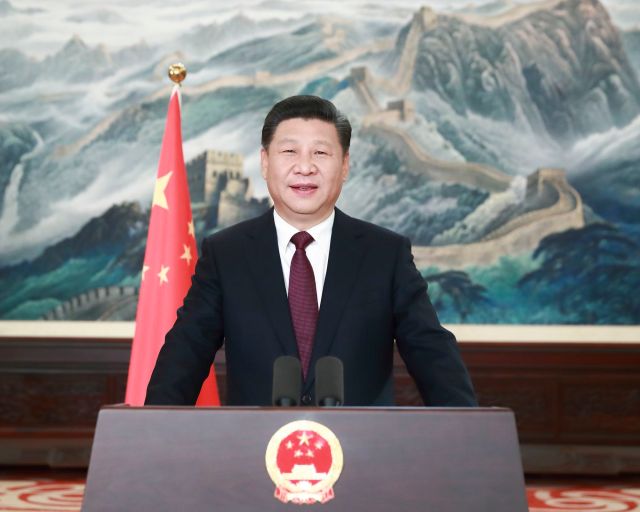

Xinhua/SIPA USA/PA Images

Vast economic and social transformations generated great European literature as the examples of Charles Dickens, Victor Hugo and Émile Zola suggest. Nowadays in the West, even major events like 9/11 or the 2008 financial crash can’t generate a half-worthy fictional response.

For something worthy of great works one should begin with contemporary China, which is engaged in relocating three quarters of its 1.4 billion population into towns and cities by 2030. In addition to such conurbations as the Pearl River Delta with 46 million inhabitants, China has 221 cities of over a million people. Few people could name a handful of these – and by way of comparison the equivalent European figure is 35.

Other statistics almost defy reality, notably that China consumed more cement between 2011-13 than the US did in the entire twentieth century. “Almost defy” because the International Cement Review did check the fact and found it was accurate. China is also transforming its economy from a reliance on capital goods and cheap exports to high value exports (including nuclear power plants) and domestic consumption by the country’s burgeoning middle class, which nowadays easily dwarfs the population of Europe. Uprooting hundreds or millions of people, as well as policies like the one-child policy, have enormous social and psychological effects, from creating selfish little princes or decoupling sexual pleasure from reproduction in the latter case.[i]

Yan Lianke is one of China’s greatest contemporary novelists. Born in Henan province in 1958, Lianke has published fourteen novels, though those available to Mandarin readers (when they are not banned entirely) often omit the ‘fuller’ versions published abroad. In 2014 he described his subject matter:

“When I look at contemporary China, I see a nation that is thriving yet distorted, developing yet mutated. I see corruption, absurdity, disorder and chaos. Every day, something occurs that lies outside ordinary reason and logic. A system of morality, and a respect for humanity that was developed over several millenniums is unraveling.”[1. Yan Lianke ‘Finding Light in China’s Darkness’, New York Times, 22 October 2014]

A CITY CALLED EXPLOSION

One of his recent novels is The Explosion Chronicles. The fictitious author/narrator (Lianke himself) accepts a big fee to abandon a novel, so as to knock into shape a rough and ready account, based on local gazetteers, of the mushrooming of a small mountain village in Henan called Explosion into a town, county and then a provincial-level megalopolis of 20 millions in a fifty years period.[2. Yan Lianke, The Explosion Chronicles, translated by Carlos Rojas (London 2016)]

The village’s transformation stems from its proximity to an incline where freight trains slow, enabling the more enterprising inhabitants to steal goods from the open wagons. They start with coal and move on to clothing. The young female population simultaneously migrates to towns to work in the euphemistically named entertainment industry, returning to set up businesses that include saunas, nail bars, restaurants and the Otherworldy Delight red light district. Roofs switch from being thatched to tiled, a key mark of prosperity. Factories and mines proliferate, as do pharmaceutical firms after the air becomes too toxic to breath. To lure rich American investors, the city recreates the sensual delights and carnage of Vietnam (using the population to re-enact Apocalypse Now) to distract and shame a CEO whose penchant for young Vietnamese prostitutes made him initially favor Southeast Asia over Explosion. Scrupulous, the rulers of Explosion are not, persuading over-sixties to vote for them in pseudo elections with promises of burial before the town adopts compulsory cremation to free up development land.

The human drama derives from the Macbeth-like rivalry of the Kong and Zhu families, which partially merge to promote Explosion’s development from model village to megalopolis. Kong Mingliang becomes the city boss, while his younger brother rises up through the army, with his own force fighting mock battles with powers that disrespect China. Mingliang never shakes off his origin as a thief, filling entire cabinets in his palace with the trivia he steals while attending ever more important meetings in the capital.

Lianke uses mytho-realist techniques to portray the confusion of cause and effect in modern China. To reflect the sheer speed of Explosion’s growth, time accelerates, with flowers and trees blossoming and wilting at an alarming rate and in line with the doings of the Kong brothers. The vast city which results even seems to control the climate, as indeed industrialisation and urbanisation have done in unfortunate ways. When Mingliang says ‘Snow’, it does. When it all goes horribly wrong, all the clocks stop and fall off the walls.

OPENING DOORS TO FLIES

Lianke’s novel is a veiled commentary on the social impact of the liberalising economic reforms associated with Deng Xiaoping from the late 1970s onwards. In addition to looking at best practice in Japan, South Korea and the US, and involving the entrepreneurial talent of the Hong Kong Cantonese, Deng encouraged a buy-in by the Communist Party after the lethal chaos inflicted on China by Mao during the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution. Mega cities like Shenzhen were created in a kind of frenzy, to be followed by the Pudong district of Shanghai under Deng’s successor.

The cadres were insinuated into every major enterprise (nowadays even Walmart has a branch) while at every level, officials were encouraged in competitive development of their fiefdoms. Deng employed a characteristically homely metaphor to indicate he was relaxed about corruption: ‘When you open the door, flies get in’ as he put it[3. Ezra Vogel, Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China (Cambridge Mass 2011) is a fine exhaustive biography].

CORRUPTION

Corruption in China has never matched the disastrous kleptocracies of Africa, which permanently cripple entire economies, and nor is it comparable with, for example, Mexico, where graft accounts for between 2% and 10% of GDP and drug cartels have more firepower than the army.

The decision in 1984 to decentralise appointments and promotions within the Party nomenklatura, was followed in the 1990s by decentralised control of assets, whose effect was like taking the lid off a jar of jam next to a wasp’s nest. It has resulted in a highly amoral and unequal society, which fitful anti-corruption drives under Jiang Zemin or Hu Jintao did little to correct[4. The best book on corruption in China is Minxin Pei’s China’s Crony Capitalism. The Dynamics of Regime Decay (Cambridge, Mass 2016)].

Under China’s current powerful core leader, Xi Jinping, things are different, with the occasional gust of wind becoming a permanently chilly air. For the last four years, Xi has encouraged a massive clean up of corrupt Party officials, masterminded by a widely-read and genial historian, Wang Qishan, who heads the Central Discipline Inspection Committee. He is described as “the handle on President Xi’s knife“.

China’s most popular TV drama ‘In the name of the people’ has dramatised the attempts to clamp down on corruption.

FOLLOW THE MONEY

Typically, killing high level ‘tigers’ as well as swatting ordinary ‘flies’ is competitive, with local anti-corruption units competing to score the highest number of arrests. A multipart TV series In the Name of the People, has dramatised these investigators. Corruption in China is certainly dramatic because the highest 100Rmb banknote is only worth $16. Ill-gotten gains always involves pallets or shedloads of cash, therefore – not to mention coffers of precious stones or drugs.

Nearly a million cadres have been investigated for corruption, and more than two hundred thousand have faced Party courts. If one multiplies that by family members who benefit from corruption, Xi is treading on the feet of many people – though should the accused commit suicide, their relatives get to keep the loot, which may explain a lot of office hangings and leaping from high windows in recent years.

The obvious motive behind this zealotry is that corruption will undermine the legitimacy of the ruling Party, whose legacy capital – like that of all national liberation movements – diminishes the further one moves from a Revolution whose centenary China will celebrate in 2049. The Algerian FLN or South African ANC have much the same problem, without China’s tight controls or a ruling party whose membership is larger than the population of Germany at one member for every sixteen people.

Xi has also very visibly struck down potential adversaries and rivals, notably the bumptious neo-Maoist Bo Xilai and then his successor in Chonqing, each of whom duly appeared (black hair dye and razors no longer available in the cells) in court next to statuesque policemen. Even the head of the secret police, Zhou Yongkang, was not immune, and nor are the families of Xi’s immediate predecessors. Corruption in the PLA has also led to the prosecution of over 200 men above the rank of lieutenant colonel, and including 37 major generals, mostly for selling promotions.

BACK TO BUDDHA AND CONFUCIUS

But the anti-corruption drive is only part of a much larger project to re-moralise Chinese society, to make it fit for the 80% of Chinese students studying in the West who nowadays choose to go home after sampling the delights of US cities like Beirut and Mogadishu on a bad day. This development might even warm the hearts of such western conservative moralists as Christopher Lasch or Gertrude Himmelfarb[5. Gertrude Himmelfarb, The De-Moralisation of Society. From Victorian Virtues to Modern Values (New York 1996) and Christopher Lasch, The Culture of Narcissism. American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations (New York 1991) are typical of the genre.], who deplored the abandonment of Victorian Values and the slide into amoral relativism from the Sixties onwards. Who knows? Xi and his colleagues might even have read them too, since China’s leaders are more familiar with Dickens or Alexis de Tocqueville than most western politicians.

Anti-corruption drives attack symptoms rather than the underlying pathologies of a society in advanced moral decay and where trust – in the food one eats or the water one drinks – is in short supply. Under Xi, the Party has clamped down on conspicuous consumption, limiting the number of courses at official banquets, binge gambling in Macau and by slapping taxes on imported luxury cars.

This is easy to enforce in a country where the many lowly moralists have mobile phone cameras, to snap the different expensive Swiss watches an official wore each night of the week and where social media like Weibo (the Twitter equivalent) may be tightly politically controlled, but ‘hate speech’ and libels rage without hindrance in the absence of a western-style PC thought police. Try calling Barack Obama ‘O Black’ or all Muslims terrorists on Twitter.

In a significant rejection of Maoist iconoclasm, President Xi is attempting to revive traditional Chinese thought as the ‘soul’ of the nascent nation, along with a assertive patriotism based on claims to US-style ‘exemptionalism’ from laws and rules both great powers do not like. The aim is to fuse this with the 12 core socialist values[6. These are prosperity, democracy, civility, harmony, freedom, equality, justice, the rule of law, patriotism, dedication, integrity and friendship. Several of these appear to have gone into abeyance though patriotism and the work ethic are fully visible. I’d add a kind of pragmatic mental steeliness, which seems in short supply in the sentiment suffused West.]. Strikingly, his Classical Aphorisms By Xi Jinping (2015) contains not a single reference to Marx or Mao, but calls to draw on China’s deep historic culture abound – even if some suspect the fusion will be a pudding without a theme.

This is intended to combat both domestic moral atrophy and deleterious foreign influences, as teen idol Justin Bieber discovered when he was recently banned from China, joining the likes of Lady Gaga and Brad Pitt until they grow up[6. Jiayang Fan, ‘Why Justin Bieber Got Banned From Performing In China’, The New Yorker 26 July 2017]. The neo-traditionalist message is being disseminated to schools, the armed forces and prisons. If it means selectively coopting Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism – China’s traditional creeds – then so be it, regardless of what happens with the minority faith of Christianity or the pernicious totalitarian sect Falun Gong. In addition to visiting Qufu, Confucius’s home town, Xi has hosted Taiwan’s top Buddhist monk, Hsing Yun, nowadays a bestselling author in China. Senior members of the Politburo Standing Committee have also visited temples in Tibet and a mosque in Xinxiang[7. ‘Xi Jinping hopes traditional faiths can fill moral void in China’, Reuters 29 September 2013].

Just because China’s leaders, commentators – or novelists for that matter – detect a moral crisis does not mean that there is one. Our own history is littered with what amounted to moral panics. Anthropological studies of Chinese society do not show a society bereft of ethics, and arguably it is a very traditional concern with one’s own family and of not getting involved in the affairs of others lest it rebound on you, that led to shocking events where people pass by when a child or old person are knocked down by cars[8. Charles Stafford (ed), Ordinary Ethics in China (London 2013); and Lijia Zhang, ‘How can I be proud of my China if we are a nation of 1.4bn cold hearts?’, The Guardian 2 October 2011].

We began with a fictitious city called Explosion, a satire of how Shenzhen went from modest dimensions to home to 12 million people in a generation. Xi is building his own city, Xiongan, (meaning ‘magnificent peace’ in English) outside Beijing. It will be a green and smart city, with a carefully selected population, and none of the gated inequalities in which middle class Chinese exclude the migrant poor as if they were another race. Private real estate transactions will be banned[9. George Chen, ‘Xiongan: A New City for the Xi Jinping Era’, The Diplomat 30 May 2017].

Whether it exemplifies Xi’s American-style China Dream remains to be seen. Perhaps one day Yan Lianke will write about that project and a China that has been re-moralised?

Michael Burleigh’s The Best of Times, The Worst of Times: A History of the Present is published on 2 November by Pan Macmillan

***

MORE ON CHINA

Michael Burleigh: One Belt, One Road: How China’s ambitions span the globe

Jonathan Aitken: He’s trying, but China’s Church is too big for Xi to suppress

Benedict Rogers: The world cannot ignore China’s worsening abuse of basic human rights

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe