Jack Ewing’s book on VW’s cheating of environmental regulations

There is something mendacious about the Volkswagen Beetle as a great symbol of 1960s counterculture. The bug-eyed vehicle of the Summer of Love, social liberation, and the anti-war movement was dreamed up as a Nazi prestige project, built by slaves with money stolen from labour unions, and driven by elites. Herbie was of Hitler’s creation.

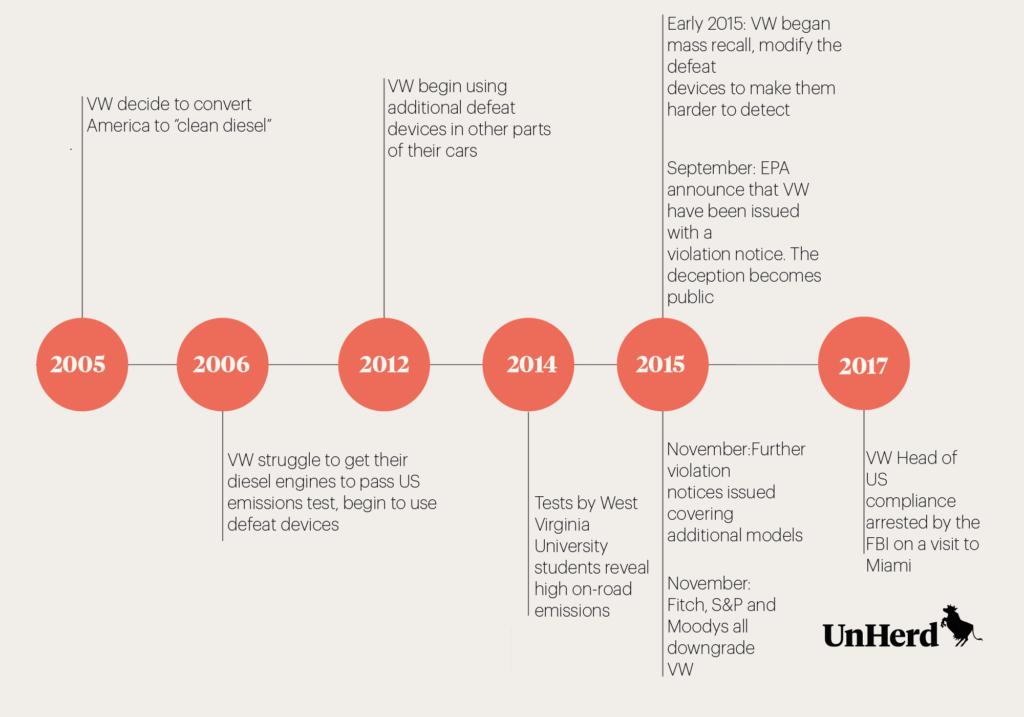

It would not be the last time that Volkswagen’s social credentials were based on soft ground. In 2015, the company’s missionary devotion to ‘clean diesel’ was exposed as a poisonous lie. Eleven million cars had been fitted with a ‘defeat device’, software that cheated emissions testing. “Volkswagen was involved in one of the greatest corporate scandals ever.”[1. Ewing J, Faster, Higher, Farther: The Inside Story of the Volkswagen Scandal, Bantam Press 2017 p. 208]

These are the words of Jack Ewing, European economics correspondent for the New York Times, who had been covering Volkswagen when the scandal made headlines.

This was to prove no normal tale of corporate fraud. No-one had lined their pockets with gold. There was none of the greed of Enron, only a hunger to go faster, higher, and further than anyone had before.

“This whole scandal was uncovered by a group of graduate students at West Virginia University with a $70,000 grant.”

Ewing is telling me what first drew him to look deeper at the downfall of a firm synonymous with German economic power.

“And that is all it took to really shake the foundations of this enormous carmaker.”

It was a modern day Aesop’s Fable, a corporate giant undone by its own arrogance, complacency, and the voices of the unheard. The makings of a book were there, and Ewing’s Faster, Higher, Farther: The Inside Story of the Volkswagen Scandal, is the result.

The book covers the history of Volkswagen, from the days of Hitler’s Herbie, to the ongoing fraud cases in US and European Courts. In places it is a rich economic history, particularly in its discussion of the importance of the VW brand to Germany’s economic renaissance after the Second World War.[2. Ewing J, Faster, Higher, Farther: The Inside Story of the Volkswagen Scandal, Bantam Press 2017 See Chapter 3: Renaissance]

In the era of Cold War competition that followed, VW became a pin up for free-market capitalism against Soviet communism, despite being state owned until 1960. In others, it becomes a family biography, looking in particular at Ferdinand Piëch, CEO of Volkswagen from 1993 to 2002 and the grandson of Ferdinand Porsche who worked with Hitler to design what later became the Beetle. The family tree present at the beginning of the book offers an early clue to the centrality of the family story to Volkswagen’s fate.

Together, these strands deliver a compelling commentary on how corporate culture influences long-run success in business. As CEO, Piëch ran an authoritarian regime, obsessed by empire building and aggressive in its pursuit of ambitious long-term goals. He built a corporate culture that outlasted his days at Volkswagen. As Ewing comments:

“If you want to trace the origins of the company ethic… I think you need to go back to that period. Market domination appeared to be the one and only objective, and by all means necessary.”[3. Ewing J, Faster, Higher, Farther: The Inside Story of the Volkswagen Scandal, Bantam Press 2017 p. 66]

The culture may have delivered modest efficiency gains, but over time its legacy proved bleak. It is a pertinent reminder that despite today’s concern about “quarterly capitalism”[4. UnHerd briefing on short-termism https://unherd.com/briefings/short-termism-briefing/], an excessive focus on long-term ambition at all costs led to catastrophic short-term cheating of environmental regulations by Volkswagen.

It was a culture that prevented VW from using industry developments like AdBlue, because it preferred to stick to its (inferior) proprietary technology. The result was that VW engines could not keep up with emissions standards and maintain market share. The VW obsession with market domination at all costs drove them into the arms of deceit.

It was a culture that saw Volkswagen meet the discovery of the defeat devices with obstinacy and wilful ignorance. As the net closed in, VW recalled cars, NOT to remove the devices, but to make them harder to detect.[4. Ewing J, Faster, Higher, Farther: The Inside Story of the Volkswagen Scandal, Bantam Press 2017 p. 183] Executives fed false information to US regulators.[5. Ewing J, Faster, Higher, Farther: The Inside Story of the Volkswagen Scandal, Bantam Press 2017 p. 197] Countless times they could have come clean, and countless times they doubled down on the deception. As Ewing reveals the scale and cost of the lie, the story’s main protagonist, Ferdinand Piëch, becomes, through his legacy, chief antagonist.

While it retains all the credentials of a serious work of non-fiction, it sometimes feels like Ewing’s work would be every bit at home on the fiction shelf. His seamless blend of history, biography, and narrative weaves a structure and plot line worthy of any bestselling thriller. That it is a very real deception for millions of consumers only heightens the desire to peek at the ending to see if justice is served.

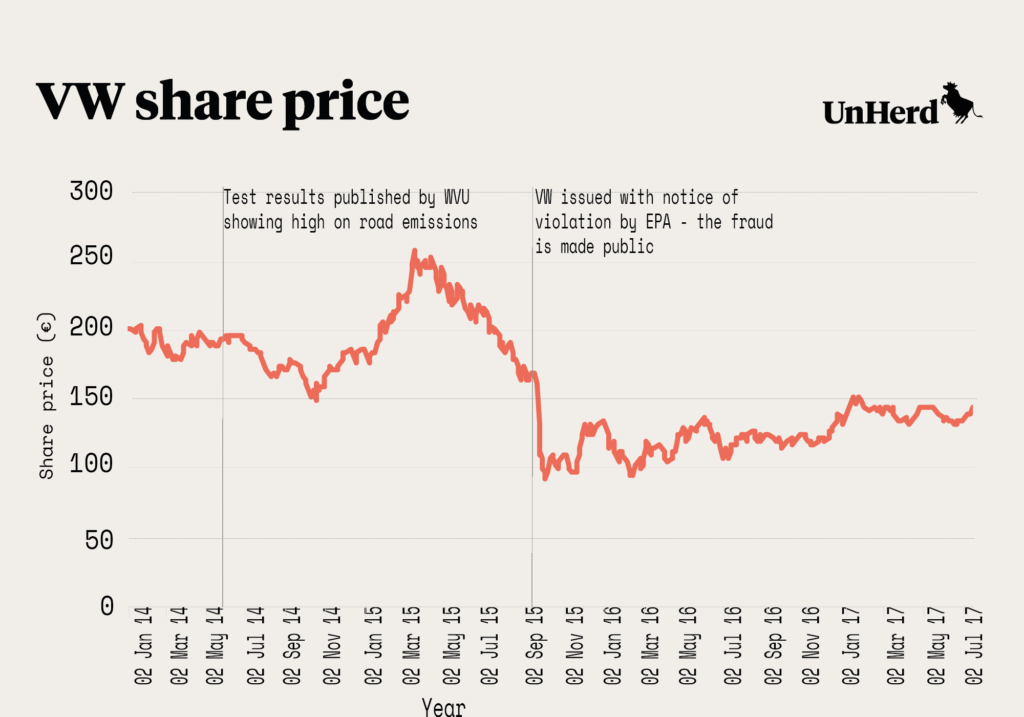

Ewing seems quietly optimistic that the markets will punish VW; the company has already seen operating losses and credit rating downgrades. Ultimately though, you are left feeling that justice has not been served, which is perhaps where Ewing’s book has most impact. It is a superbly researched, shocking, and absorbing read, but it leaves you feeling disappointment. Disappointment because the system does not work. Faster, Higher, Farther has the most power in the systemic failures it reveals.

https://soundcloud.com/user-970100804/how-to-cheat-an-emissions-test

Here it becomes a reflection on the problems of crony capitalism. The weakness of European regulation and enforcement is plain, and as Ewing discusses with me, structural. Business is too close to regulators, a problem in the auto-industry driven by Germany’s economic dominance in Europe, and the auto-industry’s dominance in Germany;

“If you look back at the last couple of decades, time and again the German government went to bat for the German car industry and that led to this very weak regulatory structure.”

The problem too is weak mechanisms of corporate oversight. While Germany boasts stronger stakeholder capitalism than the UK or US through worker representation on company boards, that did not help hold Volkswagen executives to account. Management just went to extraordinary lengths to keep labour on side. And the remarkable thing? As Ewing remarks;

“There are no real consequences for top management in something like this, and at Volkswagen they didn’t even really lose their jobs.”

Ewing is clear that there is a need for outside scrutiny:

“I think [that] is missing in a lot of companies where the Boards are pretty much people who are close to the top management… There’s really no outsider saying, well wait a minute, this is how the rest of the world sees this.”

How the world sees it matters for Germany. Much of its business model is based on superior engineering sold at a premium. But Ewing insists that it is very much a psychological thing, and if they lose it, they cannot compete with the lower costs of the likes of Toyota. Germany should be worried, thinks Ewing.

In the end, perception may prove to matter. After all, VW was a propaganda exercise that went on to become the largest car maker in the world. It was born from a lie. Perhaps it will die at the hands of one too.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe