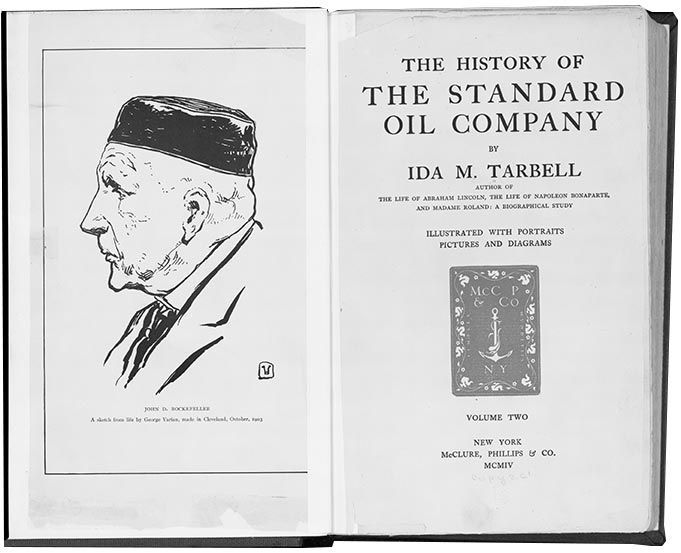

“That misguided woman!”

That’s how John D Rockefeller described Ida Minerva Tarbell. Their relationship was strained, bordering on mutual obsession, although they never actually met. Yet their confrontational standoff reverberates to this day. Just as it should.

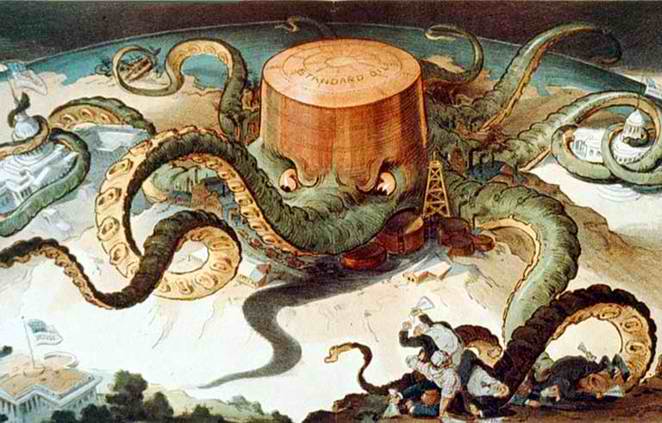

The world’s first billionaire, Rockefeller was the business genius who, in the late nineteenth century, came to dominate America’s early oil industry. A struggling journalist from small-town Pennsylvania, Tarbell was the spinster who, after painstaking research and showing enormous courage, exposed Rockefeller’s illegal methods, bringing the oil titan to heel.

Understand Rockefeller versus Tarbell and you’ll understand the importance of a free press – and, in particular, investigative business journalism. Understand Rockefeller versus Tarbell and you’ll understand the colliding forces that must be balanced to make a capitalist society work.

Our story begins at ‘Oildorado’

The global oil industry today generates revenues of over $1,000bn a year. Extracting and marketing hydrocarbons is, by far, the world’s biggest industry. It all began, though, in 1859, in a forest to the west of the Appalachians, on what was then the God-fearing American frontier. An eccentric backwoodsman called Edwin Drake had been told the thick, smelly discharge sometimes found on forest floors in Pennsylvania might be usable in whale-oil lamps. So he rigged up a steam turbine and started boring a hole, just outside a small town called Titusville. After a year of trying, Drake finally struck black gold, sparking a drilling frenzy. “Oildorado” saw farms upended and virgin forest stripped. A slow-paced, agrarian community became a chaotic, money-making free for all.

When Drake discovered oil, Ida Tarbell was two years old – her family living close by. Growing up amidst the depravity and destruction of this oil bonanza, she buried herself in books. The young Tarbell, though, her later writings show, was alive to the mud, the lawlessness, the forests of wooden-drilling derricks. Oil changed everything in Titusville, bringing big characters, chancers and new technologies to a town transformed by crude.

As capital poured in, an oil industry of sorts began to emerge. A young book-keeper-turned-businessman, Rockefeller built a small refinery in nearby Cleveland, Ohio, turning oil into usable fuel. His operation – Standard Oil – was ruthlessly efficient, and began taking over competitors. By the start of the 1870s, just a decade after Drake’s discovery, Cleveland was America’s oil refining hub, with Standard controlling 10% of US refining capacity.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe