Time tends to distort in our minds, so that we take on board the collective memory of older generations and assume it happened to us, too. This perhaps explains why there are so many books aimed at countering the history we were supposedly taught at school or were raised to believe, all of them actually aimed at the history our grandparents were taught.

The latest is Otto English’s Fake History, but there is a whole range from James Felton’s 52 Times Britain Was a Bell End, to Afua Hirsch’s We Need to Talk About the British Empire.

The authors are all around my age or younger, and when I was at secondary school in the 1990s it’s safe to say none of my teachers were members of the Empire Loyalist movement. We didn’t have a map of the world painted pink; we were never taught Our Island Story. The idolisation of Empire did once exist, but it’s been gone for generations. English, Felton and Hirsch are arguing against a ghost.

The very reason their books are so popular is because the average book-buying member of the public has been largely raised in a milieu that agrees with them.

The West’s cultural revolution is more than five decades old now; it would be like a book being published in the Soviet Union in 1970 countering all those tsarist myths you were taught at school. 52 Times Imperial Russia was a Bell End.

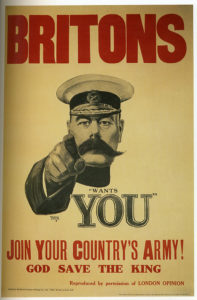

France v Germany in 1914 was something akin to a battle between civilisation and barbarism. No one in Britain cheered the arrival of war and no one said “it would be over by Christmas”, while lots of generals died rather than sitting back at HQ with Capt Darling.

The second myth is that the industrial revolution was wholly negative (certainly the impression that I was given at school). The focus was on the first half of the 19th century, when living standards remained static and conditions in industrial cities were very grim; life expectancy fell to the teens for some social classes in industrial England.

Much of this stems from Engels, who was writing in the 1840s and whose work went onto influence Arnold Toynbee in the early 20th century when the Victorians became unpopular. Yet life certainly wasn’t idyllic for the agricultural forefathers of these workers either. From around 1850 living standards rapidly shot up, and even working-class Britons in, say, the 1880s were immeasurably better off than any of their predecessors in history. The industrial revolution was great!

Between the Norman Conquest and the Second World War Britain had very little immigration, with only two significant waves from outside the UK, the Huguenots and Russian Jews – and there would have been vanishingly little racial diversity outside of ports.

National myths say more about prejudices of their own age than about the history they claim to represent. It’s therefore the myths we still believe that we should pay the most attention to.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe