One morning in the 1970s the wife of a Wigan clergyman opened her curtains to observe: “darling, the garden’s vanished.” The day before it had been the Sunday School treat. In the night the badly backfilled remains of a forgotten ‘bell pit’ silently collapsed — a small coal mine, dug by hand perhaps two centuries earlier. Today, the entire industry has been grassed over, but its presence is still felt not far beneath the surface.

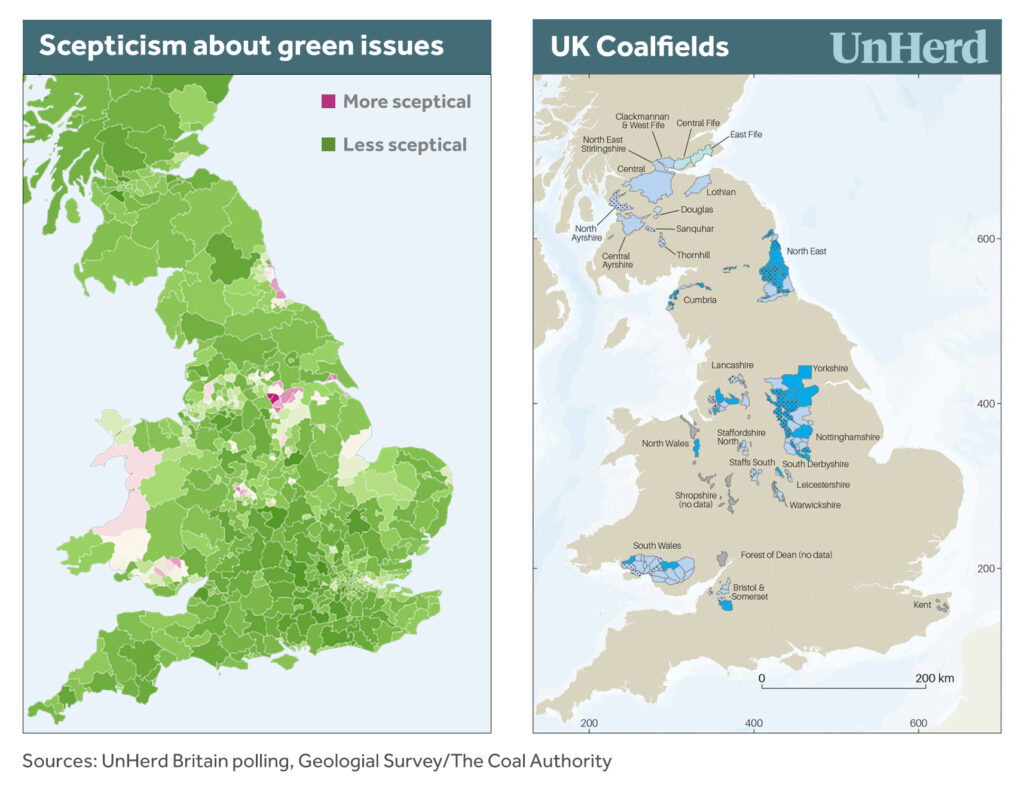

Recent polling by UnHerd found that most of the country supports the Government spending lots of time and energy on green issues. But old coal-mining centres like Wigan make up a handful of areas that remain sceptical. The values of Wigan were shaped underground: hard work, stoicism, bawdy humour, loyalty, and an aversion to pretensions. The town’s motto is ‘Ancient and Loyal’.

In fairness, some green policies around here have been very successful. There are now swathes of green space, and wetlands created by subsidence, where 50 years ago collieries and slag heaps stood. People inhabit the landscape. Fishing and shooting are popular. Whole landscapes have been regenerated since the ‘60s, by government-sponsored environmental policies. These green initiatives engaged communities in improving their own neighbourhoods, removing the toxic legacies of the old industries from the soil. They have demonstrably improved quality of life, and turned what had been private places of exploitation into new common land for recreation.

In Biden’s America coal remains a big industry, but in Britain it’s over. Few old miners would want to reopen the pits. They know coal was dirty, and deadly. It killed many of them. For a time they held sway in British politics, bringing down governments. While U-boats sank tankers, coal saved the day. Perhaps that memory is one of the reasons why there is a striking correlation between the old colliery districts and greater scepticism about the British policy consensus around Net Zero. It isn’t that people in the old mining towns want to go back to the dirtiest fossil fuel, but there is a greater scepticism about the fruits of the green agenda, particularly around energy security and prices.

There’s another correlation: these communities voted Leave. The Wigan miners welcomed George Orwell in the 1930s, but he recognised their honourable tradition of mistrust of intellectuals, ideology and schemes originating among people who have never got their hands dirty. The persistent failure of the old Coal Board’s futile attempts at carbon capture, ‘Clean Coal’, vindicated this mindset. The former mining town of Doncaster is one of the least enthusiastically green in the country, but continues to elect Ed Miliband MP. He is perhaps the principal architect of Britain’s push away from coal in the 2010s, driven by the commitments he wrote into the 2008 Climate Change Act. During the last decade, coal has faded from a dominant to a diminutive part of the British energy mix.

The case of shale gas vindicates the miners, not least since the invasion of Ukraine. Fracking was doomed in Britain by the vocal concerns of homeowners, opposition of environmental campaigners to any new fossil fuel extraction in the UK, and the sunny confidence of ministers that Britain would always be able to buy gas cheaply. The former mining districts, where much of the shale lies, are now among the poorest in the country, and policies that put fuel bills up fall heaviest on the poor.

In the early 2010s, when exploration of Lancashire shale was first mooted, there was excitement again in some of Wigan’s vicarages. The Victorian rectors of the town had built schools and churches with the profits of coal extracted from their land. Might there be a second bonanza for parochial balance sheets, from cleaner shale gas? Policy which leans on the coal miners’ grounded communitarianism, rather than concern over house prices from the anti-frackers, could yet save Britain again.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeYou have, perhaps inadvertently, expressed a truth. Anti frackers don’t really object to fracking (of which they know little) as such, although they happily co-opted this unfamiliar word as a scare tactic.

They’re simply against gas production.

If we could create a source of energy from the fervent rhetoric, we would be ‘saved’.

Hot air fills balloons that are vulnerable to pop-guns

If we could create a source of energy from the fervent rhetoric, we would be ‘saved’.

Hot air fills balloons that are vulnerable to pop-guns

You have, perhaps inadvertently, expressed a truth. Anti frackers don’t really object to fracking (of which they know little) as such, although they happily co-opted this unfamiliar word as a scare tactic.

They’re simply against gas production.

I often wonder what the local response to fracking would be if there was a local dividend from extraction in the form of an investment trust (or some such vehicle) to provide local improvements in infrastructure.

I often wonder what the local response to fracking would be if there was a local dividend from extraction in the form of an investment trust (or some such vehicle) to provide local improvements in infrastructure.

New TV sport? Miners clearing eco protestors ?

I’ll buy that for a dollar!

I’ll buy that for a dollar!

New TV sport? Miners clearing eco protestors ?

Why has that map of Great Britain been chopped just south of Aberdeen? I’m keen to know what Aberdonians think about net zero.

Why has that map of Great Britain been chopped just south of Aberdeen? I’m keen to know what Aberdonians think about net zero.

This is exactly why Wales needs to separate from the UK. With a history of managing the devastation of industry, with a small population, with plenty of land for animal farming, with the real possibility of tidal power, with land for wind power, with 11,000,000 tourists per year, with the scientific knowledge in places like Swansea University, Wales can leave England behind.

When England is obsessed with the latest trend and fashion and gets ever more woke, Wales could easily be a net seller of energy to England for ever. It is possible to achieve this with leaders who are driven to succeed…..and there is the problem.

Well yes, Chris, but with the right leaders the UK could do all that.

More than happy to offload Wales and the Scoti, like a pair of ball and chains to England.

I’ve read this comment before and I’m astonished you still seem to believe this stuff.

There are many fallacies in your arguments, but here are three to get started:

Good though Swansea University doubtless is, I don’t think there’s too much dispute that the world class universities in London, Cambridge and Oxford are in a different league.

English farmland is also – on average – far more productive than Welsh.

Young Welsh people will continue to move to London for the best paid jobs (as will Scots).

Nothing against Wales, but your perspective on this seems badly warped.

With a small population of tax payers* and a hugely out-of-proportion national and local (un)civil service whose wagebill completely outstrips tax income. *of which I am one

You may have forgotten that Legion of Marxist/Socialist toads that emanated from the ‘Valleys’, but we haven’t.

A financial disconnect. With Wales? They’ll be fine, let em sink and let’s circle the waggons.

Devolution was destruction without insight.

We now have a schizophrenic national government, supposedly of one-mind but unable to reign in the alternative personalities

The rusting hulks of abandoned tidal power projects will litter your coast, as they have done everywhere this “real possibility” has been tried for any length of time.

Speaking of tourists, did you know that the two most touristed countries in the world, USA and France, are also the ones with the most nuclear power stations? Far less destructive than wind farms.

Unfortunately, as you acknowledge, Wales is governed by hopelessly woke crypto-communists, possessed of even lower levels of competence than those who have wrecked the economy of Scotland. I did notice a lot more Welsh nationalism on my last visit to watch the rugger in the Millennium Stadium (just before lockdown), with groups of young lads chanting’Welsh not British, Welsh not British’ (ironically enough to the tune of the Big Ben chimes). I wonder how much the idea is gaining ground.

Well yes, Chris, but with the right leaders the UK could do all that.

More than happy to offload Wales and the Scoti, like a pair of ball and chains to England.

I’ve read this comment before and I’m astonished you still seem to believe this stuff.

There are many fallacies in your arguments, but here are three to get started:

Good though Swansea University doubtless is, I don’t think there’s too much dispute that the world class universities in London, Cambridge and Oxford are in a different league.

English farmland is also – on average – far more productive than Welsh.

Young Welsh people will continue to move to London for the best paid jobs (as will Scots).

Nothing against Wales, but your perspective on this seems badly warped.

With a small population of tax payers* and a hugely out-of-proportion national and local (un)civil service whose wagebill completely outstrips tax income. *of which I am one

You may have forgotten that Legion of Marxist/Socialist toads that emanated from the ‘Valleys’, but we haven’t.

A financial disconnect. With Wales? They’ll be fine, let em sink and let’s circle the waggons.

Devolution was destruction without insight.

We now have a schizophrenic national government, supposedly of one-mind but unable to reign in the alternative personalities

The rusting hulks of abandoned tidal power projects will litter your coast, as they have done everywhere this “real possibility” has been tried for any length of time.

Speaking of tourists, did you know that the two most touristed countries in the world, USA and France, are also the ones with the most nuclear power stations? Far less destructive than wind farms.

Unfortunately, as you acknowledge, Wales is governed by hopelessly woke crypto-communists, possessed of even lower levels of competence than those who have wrecked the economy of Scotland. I did notice a lot more Welsh nationalism on my last visit to watch the rugger in the Millennium Stadium (just before lockdown), with groups of young lads chanting’Welsh not British, Welsh not British’ (ironically enough to the tune of the Big Ben chimes). I wonder how much the idea is gaining ground.

This is exactly why Wales needs to separate from the UK. With a history of managing the devastation of industry, with a small population, with plenty of land for animal farming, with the real possibility of tidal power, with land for wind power, with 11,000,000 tourists per year, with the scientific knowledge in places like Swansea University, Wales can leave England behind.

When England is obsessed with the latest trend and fashion and gets ever more woke, Wales could easily be a net seller of energy to England for ever. It is possible to achieve this with leaders who are driven to succeed…..and there is the problem.