The ‘new optimists’ are a loosely affiliated group of researchers, wonks and journalists who believe that, broadly, the world is getting better. On some very important metrics — like literacy and child mortality — they’re broadly correct. Perhaps human progress is real after all.

However, on other issues — especially our impact on the environment — they take the upbeat narrative too far. Consider a favourite new optimist talking point, which is that counter to eco-doomster concerns over deforestation, rich countries are experiencing afforestation.

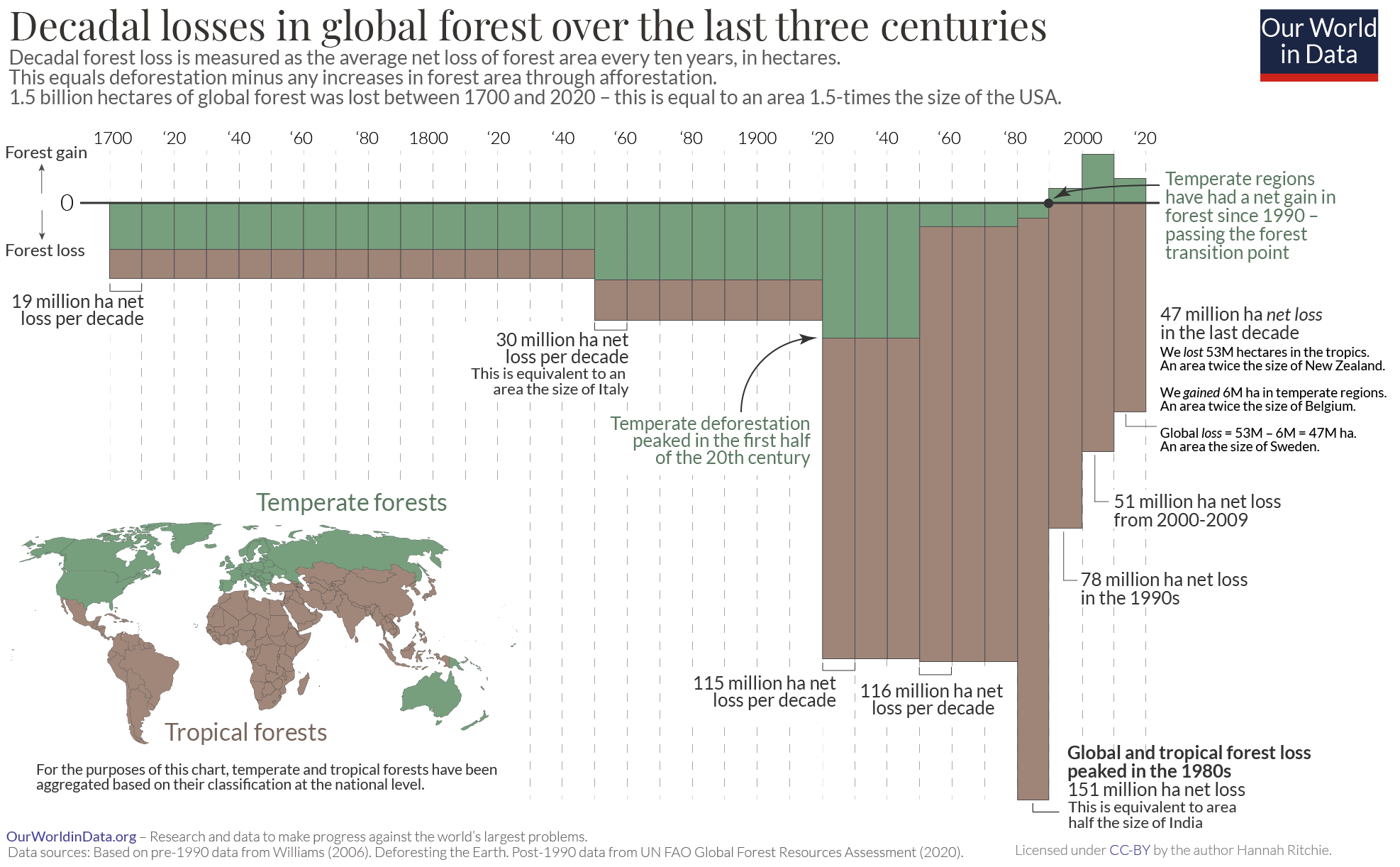

This is true, tree cover in the rich world is increasing — and has been for about thirty years. But just look at this good news story in context. The following chart comes from an article by Hannah Ritchie for Our World in Data:

As you can see, the net expansion of temperate forests since 1990 is dwarfed by the continuing loss of tropical forests. The comparatively good news is that this is taking place on a less devastating scale than in the 1980s when we chopped down 151 million hectares of forest — which, says Ritchie, is “equivalent to an area half the size of India”. Over the 2010s, the global net loss was down to 47 million hectares — or “an area the size of Sweden”.

In this regard the world is still getting worse — though not on quite the same scale as earlier decades. Then again, tropical forests have been pushed back so far into inaccessible areas that it’s not surprising that peak deforestation hasn’t been sustained. In fact, it’s precisely because so much forestry has been destroyed already that we should be increasingly worried about ongoing destruction. To reduce a habitat is bad enough; to wipe it out altogether means mass extinction.

Furthermore, westerners shouldn’t be too proud of our modest tree-planting efforts. One of the reasons why some of our farmland is being returned to woodland is because we’re importing the products of intensive agriculture from countries like Brazil and Indonesia. Just look at how many supermarket products now contain palm oil — produced from plantations where tropical forests once stood. In importing cheap food, we export environmental destruction.

Finally, the capacity to send the trends heading back in the wrong direction still exists. The technology that enabled the devastation of the 20th century is more powerful than ever before and politicians like Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro are all too willing to unleash it.

Of course, not everyone is interested in biodiversity. However, biodiversity is interested in you. All manner of pathogens lurk in tropical habitats — and the more we disturb and exploit them, the more likely it is that they’ll jump from animals populations into our own.

So, while it’s nice to be optimistic, we need to be realistic about what we’re doing to the environment and ultimately to ourselves.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe