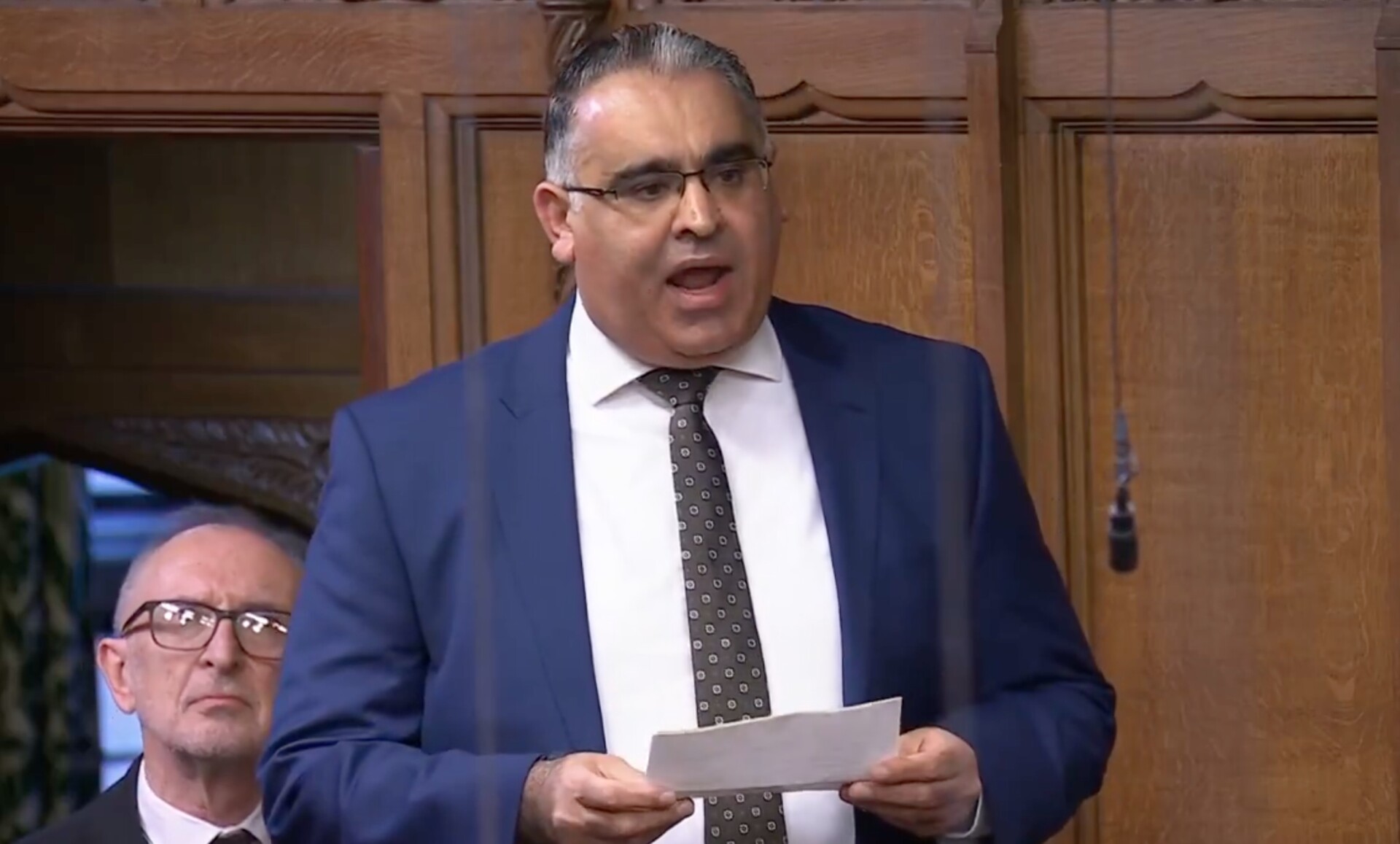

Yesterday in Parliament, Labour MP Tahir Ali asked Keir Starmer whether the Government would “commit to introducing measures to prohibit the desecration of all religious texts and the prophets of the Abrahamic religions”. Both the question and the Prime Minister’s response have already attracted a great deal of attention and criticism, but of perhaps overlooked significance is the way in which the question was introduced with reference to Islamophobia Awareness Month.

Critics of both the term “Islamophobia” and its proposed definitions have long warned that it could amount to a backdoor blasphemy law. In response, they have frequently met with scorn, derision, and allegations of Islamophobia — which you’d think rather proves their misgivings.

Now, however, the connection between Islamophobia and an outright proposal for blasphemy laws has been made aloud, and occurs shortly after the case of Samuel Paty, the French teacher who was murdered for allegedly showing his class cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad, has re-entered the news cycle. That is because the schoolgirl who originally whipped up the allegations of Islamophobia, attracting the attention of local Islamist preachers and subsequently a jihadist’s blade, has now admitted she made it up.

An allegation of Islamophobia is not simply to be accused of being discriminatory or bigoted towards human beings: it is to be accused of being against Islam, making it a short leap to the sometimes-fatal allegation of blasphemy. That leap has been made a little bit shorter by Ali’s comments in the House of Commons yesterday.

Once the allegation of either Islamophobia or blasphemy is out there, the accuser has no control over who hears it and what they see fit to do about it. Those who seek to weaponise these allegations can then use this to their advantage with plausible deniability. The French anthropologist Florence Bergeaud-Blackler discovered this the hard way last year, when her book on the European activities of an Islamist group, the Muslim Brotherhood, was met with an Islamophobia backlash cynically orchestrated by the very subjects of her research from their positions dotted around academia, civil society and the media. After receiving death threats, Bergeaud-Blackler was forced under police protection.

In Britain, we have had our own sorry episodes. Would the 2021 film The Lady of Heaven, a production by Shia Muslims which was subject to protests and was pulled from many UK cinemas over safety concerns, come under such proposed legislation?

Similarly, while Britain has not witnessed the type of Quran-burning stunts experienced by Denmark or Sweden, we had the 2023 case of an autistic teenager who accidentally scuffed a Quran, leading to death threats and a shameful and intimidating community tribunal — attended by the boy’s pleading mother and a solemnly nodding police officer. That’s not to mention the teacher from Batley Grammar School who remains in hiding, more than three years on, for doing his job.

Muslims are not immune to these dangers, either. In 2016, Glaswegian shopkeeper and Ahmadi Muslim Asad Shah was stomped and stabbed to death in a frenzied attack over videos in which he claimed to be a prophet. In Rochdale that same year, an elderly Imam, Jalal Uddin, was bludgeoned to death with a hammer over his alleged “black magic”.

No doubt some would argue that enshrining Islamophobia in law would prevent the kind of mob justice that has been brewing for some time in Britain. But this is unlikely. Would the teenager in Wakefield have been charged under such legislation? If not, can proponents of such a law explain why? Are we sure those looking to punish perceived blasphemers would be satiated? The Tehreek-e-Labbaik (TLP) movement in Pakistan is increasingly influential in Britain and a significant driver of some of the recent controversies. It needs blasphemers to sustain its energy — so where they don’t exist, it will find or even invent them.

The more we collectively try to err on the right side of blasphemy or Islamophobia allegations, the lower the bar for perceived transgressions becomes. Just ask Tom Holland, whose documentary on the origins of Islam attracted death threats, or the art history professor in the US who lost her job for Islamophobia after showing a masterpiece of Persian art depicting the Prophet Muhammad.

Now that the subject has been broached, in Parliament no less, we can expect these calls to grow louder and more frequent, and for various lobbying and advocacy groups with dubious connections to Islamist politics to join the chorus. In Starmer’s case, sidestepping the very dangerous substance of the question — rather than immediately nipping it in the bud — is clearly not the answer.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe