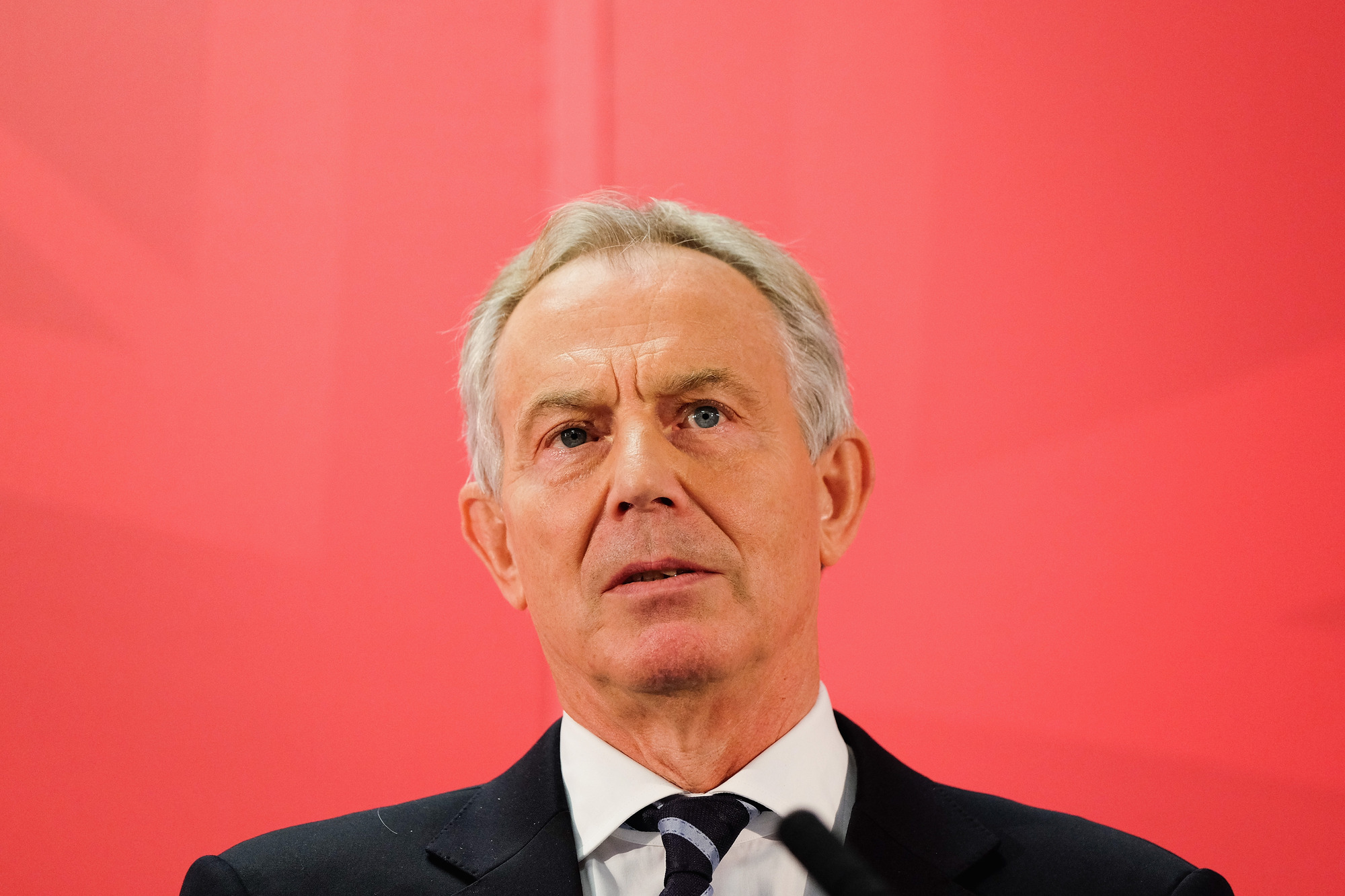

Oh Tony, you don’t make it easy for the Blairite defence. “The problem with countries that aren’t democracies,” the former prime minister claimed in a profile published today in the Sunday Times, “is they’re fine if you happen to have really smart people running them, but if you don’t, there’s a problem.”

No, that is not the problem with autocracies. They are not fine, so long as their leaders have figured out a way to ensure they are run by the enlightened. Democracy has value in and of itself. Yes, this does not mean that democracy alone is all that matters. Order, liberty, peace, security all matter too. But politics cannot be reduced solely to dry Benthamite measurement. Life itself should not be defined in this way.

Blair’s argument is revealing, nevertheless. He has long defined politics in terms of pragmatism: what matters is what works. But in his early years he wrapped such ideas in distinctly populist language. New Labour was the “political wing of the British people”, he liked to claim. Blair seemed to be able to convene directly with the British public for a while and would often declare this or that policy had more support in the country than in Parliament: from ID cards, to anti-social behaviour, law and order, and “reform” more generally.

In his pomp, Blair claimed to know both what “the people” wanted and how to deliver it. What mattered was what worked. Immigration increased because the really smart people running the system had looked at the numbers and concluded that it was good for the economy. Devolution was smart because it would kill Scottish nationalism stone dead. Open, liberal, global markets were smart because they worked.

Blairism in essence, then, was technocratic populism. Since leaving office, however, Blair seems to have largely forgotten the populism bit, retaining only the technocracy. In one sense, this is understandable, given the failures of the old political consensus which he came to embody. Iraq, after all, did not work, nor did Afghanistan. But more importantly, nor had the global financial system which underpinned the entire New Labour settlement. Smart people created a system which failed.

Today, Blair almost seems to see the need to retain popular support as a barrier to good government. “Democracy can deliver,” he insisted in his interview with the Sunday Times, “but it’s got a problem today because it is an old-fashioned politics trying to deal with a very new-fashioned world.” Putting aside the awfulness of this particular soundbite, what does he see as “old-fashioned”? On the one hand, it is “nationalism” and on the other “identity politics”.

Another way of looking at this, though, is that identity politics is the result of a breakdown in nationalism, at least of the sort needed to bind people together. Historically speaking, nationalism has been a necessary condition for democracy to flourish: for the demos to rule, there has to be a demos to begin with.

But the thing about nationalism is that it cannot be proved by clever people. It is all made up. What are nations but “imagined communities” as Benedict Anderson once put it? Technocracy, which sees the people as barriers to sensible reform, cannot inspire the sense of collective loyalty necessary for good policies and institutions to flourish. The Labour government of 1945 was nationalist to its core — as was its National Health Service.

The thing with Blair is that I also do not believe, at heart, he is a mere Benthamite either. In his Sunday Times interview, he complained that people always wanted to ascribe “some sort of malign, or let’s say benign but psychological motive” to his actions. Perhaps this is my ego speaking, but I felt this was an answer to my profile of him last year, in which I concluded that what mattered for him was power: “The power is the point.” Blair’s own account of this is that he came into politics “to make a difference”, and merely still wants to.

But this doesn’t answer the why. Why does he want to make a difference? In the end, Blair, like all of us, is a complicated man driven by many things: ego, money, status, mortality. In Blair’s case he is also a man of deep religious conviction. And he is not a Catholic because Catholicism works but because he thinks it is true.

Democracy too matters beyond its mere utility, much like many of the things ordinary people place value upon. Democratic politics is the peaceful resolution of the competing values, interests and ideas within a given group of people. Blair was once the master of this populist game and should remember the value in it, because the greatest irony of all is that if there’s one thing that doesn’t work, it’s not democracy, but technocracy.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe