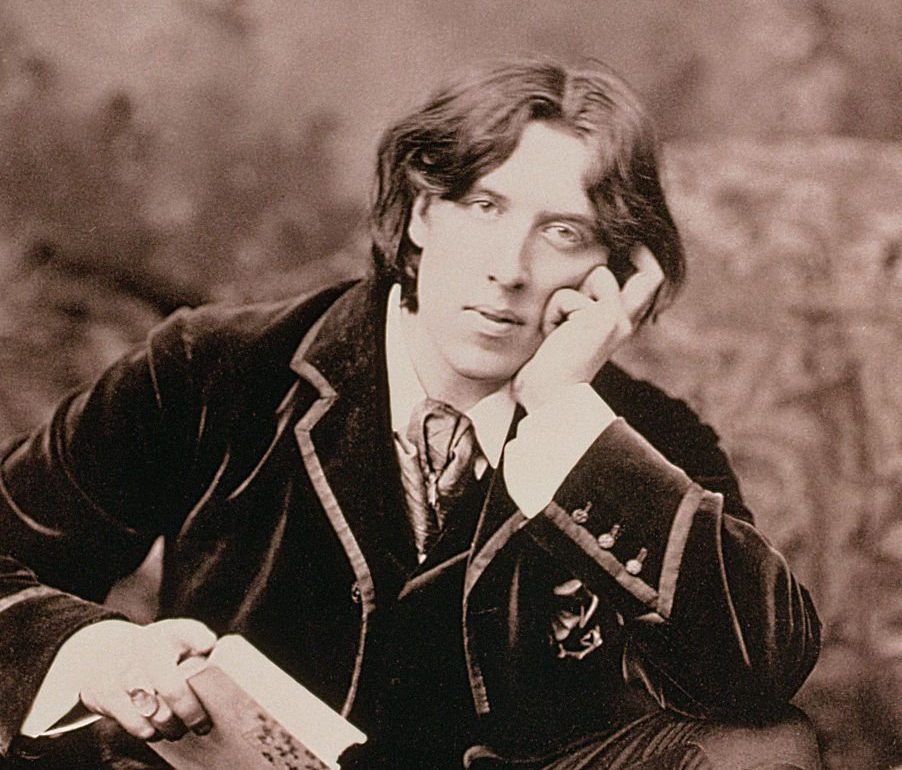

Doom is the 'purple thread' that 'runs through the gold cloth' of this Gothic novel.(Credit: Napoleon Sarony / Bettman / Getty)

In the darkest scene of Oscar Wilde’s shimmering crime novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), Basil Hallward — who made the picture — urges his muse: “Pray, Dorian, pray.” The artist then haltingly recites a couple of lines from the Lord’s Prayer. “Lead us not into temptation,” he says, “Forgive us our sins.” Finally, he pleads with London’s most beautiful man: “Let us kneel down and try if we can remember a prayer.” Instead, Dorian stands up and sticks a knife into his friend’s neck, “stabbing again and again.”

Some years before he turned to killing, Dorian had a church-going phase. “He loved to kneel down on the cold marble pavement”, Wilde tells us. He was fascinated by the “fuming censers” that London’s altar boys, dressed in “lace and scarlet, tossed into the air like great gilt flowers”. Confessionals amazed him. Could it really be that modern men and women would pause and whisper “the true story of their lives” to a consecrated stranger? Dorian might have hated the melancholy theatrics of Ash Wednesday, where the living take a mark of death — ashes and dust — on their faces. He had a horror of death. But church was just a phase for him – and having seen it, he changes.

One of the most interesting things about Basil’s death scene is that it never changes, though Wilde wrote The Picture of Dorian Gray more than once. First, a 13-chapter version of the novel appeared in an avant-garde American magazine in the summer of 1890. The following year, a 20-chapter version, the one we now read, came out with a London publisher. Recently, much has been made of the fact that Dorian Gray was edited — in part, by Wilde — to keep it out of the Victorian courts. During his calamitous trial in 1895, Wilde’s adversaries called the second version a “purged edition”. That is a hostile description. But it is still fascinating to read The Uncensored Picture of Dorian Gray, based on Wilde’s 13-chapter typescript and handwritten corrections. (He was an early fan of typewriters.) Here, Wilde shines in an unfiltered way. And he still has Basil say, just before he is murdered: “Pray, Dorian, pray.”

What is happening here? Why is the smart gentleman who fell in love with Dorian (as we would now say), and painted him because he “worshiped” him (as Basil says), now begging him to pray? “Isn’t there a verse somewhere”, Dorian’s portraitist wonders: “Though your sins be as scarlet, yet I will make them white as snow?” There is, in fact, such a verse. You can find it in the first chapter of the Book of Isaiah. But again, we might ask, what is Wilde’s uncensored aesthete doing quoting a biblical prophet just seconds before Dorian slaughters him?

The answer is that Wilde’s splendidly decadent novel is essentially Christian.

Now, this is not how most Victorian critics read The Picture of Dorian Gray. The St James’s Gazette attacked the novel for its “esoteric prurience”. A similar tone is taken by the Scots Observer. There, Dorian Gray is called “false art”. It “deals with matters only fitted for the Criminal Investigation Department”. Meaning? It is not so much a crime novel as a criminal one. And that does seem to be the insinuation. “Mr Oscar Wilde has again been writing stuff that were better unwritten.” We might call this the normal Victorian reading of Dorian Gray.

But some Victorian Christians read Wilde’s “remarkable novelette” differently. A critic writing for the Christian Leader sees Dorian Gray as a work of “subtle power”. The “gilded paganism” it depicts “has been staining the later years of the Victorian epoch”. But Wilde doesn’t whitewash Victorian hedonism. On the contrary: “In the tragic picture of Dorian Gray’s life, given up to sensuous pleasure, with its mingled culture and corruption, Mr Wilde has performed a service to his age.” Dorian’s fate is a warning, and the Christian Leader’s critic feels that “the motive dominating the writer” is redemptive. Already in the summer of 1890, then, Christians were able to read Dorian Gray as a deliciously atmospheric morality play.

Wilde himself officially denies that his novel is immoral or moral. Irritated by Dorian Gray’s detractors, he wrote a preface to the book in 1891 — a sort of manifesto — in which he famously states that there is “no such thing as a moral or an immoral book”. Whatever wickedness Dorian Gray’s haters might impute to it, the novel contains no “ugly meanings”. It is a “beautiful thing”, and beautiful things are perfectly useless. L’Art is strictly pour l’art. To even ask what a novel does is the mark of a philistine.

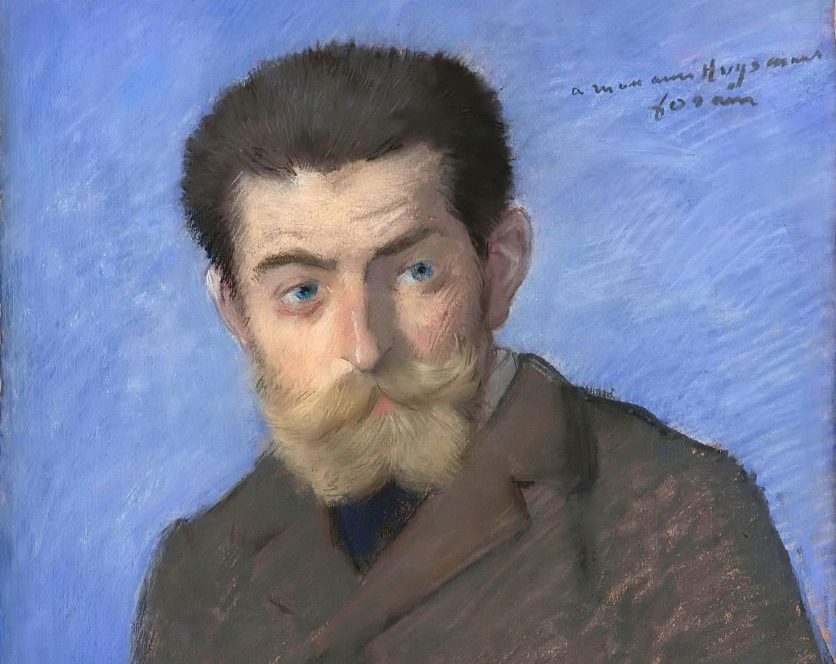

Wilde’s manifesto is charming, but not convincing. First, because he confided to friends that Dorian Gray would be “ultimately recognized as a real work of art with a strong ethical lesson inherent in it”. And second, because Dorian Gray is structured by its antihero’s obsession with a “dangerous novel” (in the uncensored version: it later becomes a “poisonous book”). Stereotypically, it is French: Joris-Karl Huysmans’s 1884 novel, Against Nature, is clearly what Wilde has in mind.

If a novel can reorient your soul and subvert your life, as Huysmans’s does Dorian’s, then novels are not useless. Whatever Wilde may say in his Dandyist manifesto, it is not out of place for us to ask: Is The Picture of Dorian Gray a “dangerous novel”? And to my mind, it is. Dangerous, and decadent, and Christian.

The figure of Dorian, a name that hints at “Greek love”, is immensely complex: because Wilde himself is. Dorian is a modern Narcissus; a pathological love of his own youth and beauty, which he senses for the first time in Basil’s painting, binds him “like a revelation”. He is also a Victorian Antinoüs. Dorian’s face, like that of Antinoüs — the Emperor Hadrian’s dashing young lover who drowned in Egypt in the year 130, and was then worshipped throughout the Empire — embodies a cultural epoch. And he is a Decadent icon: Husymans’s sickly French antihero, Des Esseintes, is outshone by his sleek English imitator, Dorian Gray.

Ultimately, though, Dorian is a symbol of doom. Of damnation, we might even say. Or that is what Wilde seems to conclude in his prison cell, half a decade after writing The Picture of Dorian Gray. As he puts it in his tremendous prison-house letter, De Profundis, doom is the “purple thread” that “runs through the gold cloth” of his Gothic novel. And this doom has a specific shape — the shape of two prayers. One that is made, and the other that is not.

There is nothing pious about Dorian’s first prayer. When Dorian sees how attractive he is in Basil’s portrait — and more importantly, how young he is — he cries out (in the uncensored version):

“How sad it is! I shall grow old, and horrid, and dreadful. But this picture will always remain young … If it was only the other way! If it was I who were to be always young, and the picture that were to grow old! For this – for this – I would give everything! Yes: there is nothing in the whole world I would not give!”

It is not so much what is said here, as it what is unsaid, that makes Dorian’s outburst a prayer — or rather, a sort of satanic incantation. For hidden in the phrase “the whole world” is an echo of one of Jesus’s sayings that the debonair cynic, Lord Henry Wotton, calls to mind in the novel’s final pages:

The elder man lay back and looked at him with half-closed eyes. “By the way, Dorian”, he said, after a pause, “‘what does it profit a man if he gain the whole world and lose’ – how does the quotation run? – ‘his own soul’?”

That is pretty much how the quotation runs. No Victorian, however louche, could forget the stern words in which Jesus warned his own decadent age — or, as he put it, his “adulterous and sinful generation” — that everyone has, or rather is, something that can be lost but never exchanged. “For what shall it profit a man”, Jesus asks in the Gospel of Mark, “if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul? Or what shall a man give in exchange for his soul?”

Dorian’s soul is the thing — or, rather, the only thing in the world which is not a thing — that he offers up when he says: “There is nothing in the whole world I would not give!” It is Dorian’s absolute sincerity which makes his wish a sort of prayer. And Wilde signals what is happening. He does not want us to miss the scene’s occult aspect. So, he tells us that the boy flings himself on Basil’s divan and buries his face in the cushions “as if he were praying”. The nightmare begins here, with a sort of prayer.

From that moment on, Dorian’s soul somehow takes possession of Basil’s picture. The artifact ceases to be a static object and takes on a “monstrous soul-life” of its own. It ceases to radiate Dorian’s boyish innocence and becomes a deteriorating “image of his sin”. Later in the novel, a woman whose life Dorian had ruined — one of many — calls him “the devil’s bargain”. “They say”, she says, “he has sold himself to the devil for a pretty face”. With his pretty face, Dorian gains the world of his day — and in the lines and brushstrokes of a once-pretty picture, he watches himself lose his soul.

At first, this horrifies him. But the further Dorian goes into “the madness of pride”, the more pleasure he takes in his picture’s decomposition. Exactly 70 years before Gustav Metzger introduced the concept of “auto-destructive art” in London, in 1961, Wilde gave us a self-destructing portrait. (The Victorians always get there first, I find.) The occult deconstruction of Dorian’s image visualizes “the real degradation of his life”.

The Picture of Dorian Gray is a dream of what Wilde calls (in the uncensored version) “the hideousness of sin”. Sin is Dorian’s doom. And the description of his spiritual hideousness, which corrupts his virtual body, seems to have been inspired by leprosy — a real affliction which is common in the Gospels. As Wilde well knew, leprosy is the archetypal sickness that Jesus cures in the four “Gothic novels” that are enshrined in the New Testament. (Are the Gospels “Gothic”? Well, they are not lacking in a sensitive protagonist, tyrannical rulers, demonic possession, preternatural cures, and persecuted innocence — and it is not for nothing that Wilde’s lurid tragedy, Salomé, is set in Jesus’ milieu.) In Wilde’s original typescript of the novel, this is how he describes the self-destruction of Basil’s portrait: “Through some strange quickening of inner life the leprosies of sin were eating the thing away.”

Dorian is a spiritual leper. His soul is collapsing in on itself. His essence is decomposing, while his surface glows. And Basil tells him, in the scene with which we began, how his drama of undoing had started: “The prayer of your pride has been answered.” It is, perversely, out of pride that Dorian relinquished his soul. It is out of pride that he chose the “auto-destruction” of his soul over the dissolution of his body. And when the novelist tells us that the “pride of individualism” is “half the fascination of sin”, Wilde is channeling hundreds of years of Christian moral theology.

But if a “prayer of pride” sets Dorian’s doom in motion — what is the other prayer that settles his fate? What is the one he never makes? Basil tells him this, in Wilde’s original draft: “The prayer of your repentance will be answered also.” What Wilde then writes could not be simpler. It could even appear to be flat:

Dorian Gray turned slowly around, and looked at him with tear-dimmed eyes. “It is too late, Basil.”

Too late to pray? Too late to repent? Too late for a prayer of repentance to be heard? Dorian, who has just told Basil that each of us “has Heaven and Hell in him”, is no longer interested in Heaven. Hell is now his scene. A double possession seems to be at work here. Not only is Basil’s picture possessed in some way by Dorian’s sick soul, but Dorian now has “the eyes of a devil”.

Could he really regain the eyes of an angel, just through prayer? That is the idea. Whatever Wilde may have believed or half-believed or wanted to believe, that is his Christian literary conceit. And it is not original to him.

I feel sure that Dorian’s dull words — “It is too late” — are lifted from a scene in Christopher Marlowe’s Tragical History of Doctor Faustus, where the “brave doctor” asks his psychic companions — one evil, one good: “Is’t not too late?” The evil angel assures him: “Too late.” But the good angel contradicts: “Never too late, if Faustus will repent.” The good angel’s reply is the radically humanizing idea behind the Gospels and the Faust myth, and the Dorian drama. (In Dorian Gray, Basil is a good angel and Lord Henry a corrupting influence.) It is never too late, if a sinner will repent.

But that is also why Wilde’s decadent, Christian novel is dangerous. “All art is at once surface and symbol”, he writes in his Dandyist manifesto, adding: “Those who read the symbol do so at their peril.” The Picture of Dorian Gray can only be read at your peril, because it is a rich dramatization of the strange fact that life can only be lived at your immense peril.

“Art is a symbol”, Wilde somewhere reminds us, “because man is a symbol”. And Dorian is a compelling figure of the weird fact that by the time we become conscious of ourselves, some prayer of pride has already been made. Some sort of fall has already taken place. And the question facing him, and us, through the rest of the drama is just this: Is it really too late for a prayer of repentance?

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe