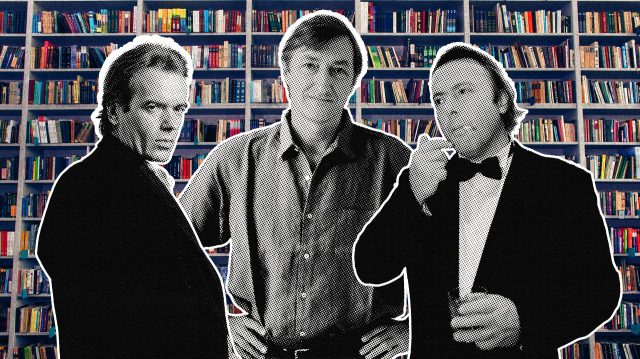

No generation of novelists and essayists before or since has so managed to combine aesthetic and intellectual ambition with outright commercial success. (Credit: Getty Images)

One of the key literary friendships of the past half-century was that shared by Martin Amis and Christopher Hitchens. As Amis himself once put it: “My friendship with the Hitch has always been perfectly cloudless. It is a love whose month is ever May.” But even they had their troubles, not least after Hitchens’s negative review of Saul Bellow’s final novel, Ravelstein, published in 2000. What Hitchens thought of as a “disobliging” piece was, to Amis, “raucously hostile” and “coldly unfilial”: Ravelstein was, after all, Bellow’s “exquisite swansong, full of integrity, beauty, and dignity”. Reading Hitchens’s review, Amis found himself “muttering the piece of schoolmarm advice” he had already given his friend “in person, more than once: Don’t cheek your elders.”

Easier said than done, perhaps. In his book-length essay Changing my Mind, published last year, the éminence grise of the British novel Julian Barnes (and erstwhile friend of both Amis and Hitchens) recounted how he had once looked down on the elder E.M. Forster for the “feeble” arguments of his Aspects of the Novel. Forster’s masterly short novel A Room With a View (1908) was, to Barnes, “a fusty, musty, dusty read, with rather antique prose”. But even worse was the fact that “Forster had stopped writing fiction at forty-five, then lived on for another forty-six years, in the process becoming a grander and grander (if still modest) old man”. But while the younger Barnes had been “less forgiving” about Forster’s literary retirement, he later came to realize that there was something honorable about packing it in: “Nowadays, I would admire a writer who falls silent because he or she has nothing more to say.”

Now, less than a year later, Barnes himself has called it a day. In his new novel, Departure(s), the narrator (also named Julian Barnes) declares: “This will be my last book.” Written with the wry intelligence and quiet irony we have come to associate with Barnes’s work, Departure(s) also displays the formal hybridity of his earlier not-quite-novels, like Flaubert’s Parrot (1984) or A History of the World in 10½ Chapters (1989). The fictional Barnes broadly corresponds with the factual one: he is a widower in his late seventies, his debut novel was called Metroland, his partner is named Rachel (Barnes married former publisher Rachel Cugnoni at a small ceremony in August last year) and he has just been diagnosed with myeloproliferative neoplasm, a “manageable” form of bone-marrow cancer. But this sounds worse than it is: “my life is not seriously compromised,” the fictional Barnes reassures us. “Unless, of course, I get bum cancer etc etc as well.”

You can tell from the phrase “bum cancer” that the fictional Barnes is hardly po-faced about his diagnosis. He keeps a contemporaneous diary throughout his time in hospital, which displays the kind of avuncular comedy we have come to associate with all of Barnes’s work (one never laughs at Barnes; at best he might persuade you to nod with a wry smile). When an A&E doctor says they “can’t say if it is or isn’t leukemia”, the narrator supposes this “sounds slightly cavalier”; when the phlebotomists draw yet more blood, he refers to it as “pints of Barnes’s Best”. But there is plenty that gets on his nerves: not just the NHS jargon (one poor soul is told that she’s on the “palliative pathway”), but also the broader “attitudes” towards cancer that “make no difference” to one’s outcome: “‘Being brave,’ or being shit-scared, or occupying a midpoint of stubborn self-deception, doesn’t alter anything.” Hitchens made a similar point in Mortality, the posthumous collection of Vanity Fair pieces about his own esophageal cancer, published in 2012: “People don’t have cancer: They are reported to be battling cancer. No well-wisher omits the combative image: You can beat this.” It’s hard to imagine Hitchens using the voguish language of “pathways”; he preferred a pithy one-liner, like “the thing about Stage Four is that there is no such thing as Stage Five”.

The cancer diagnosis leads the fictional Barnes to ruminate on death, memory, time, love and literature: all his usual themes. Indeed the claim that Departure(s) will be his “last book” is undermined by the fact that it is also all of his previous ones. Much of the material on death and memory is practically lifted from Changing My Mind, as well as the Booker-winning The Sense of an Ending (2011) and his sardonically titled memoir on mortality, Nothing to Be Frightened Of (2008). In this latest novel, whole lines are lifted or rehashed from the earlier work. The sub-plot about Stephen and Jean, two of the narrator’s university friends who attempt to rekindle their student love at retirement age, seems original enough until Barnes reheats the line “Once bitten, twice bitten” from The Sense of an Ending and 2018’s The Only Story. Is this repetitiousness a sign of fading powers? Perhaps. But as the fictional Barnes says to a friend who chides him for all the “hybrid stuff” in his writing: “I don’t mind you not liking my books, but you are mistaken if you think I don’t know exactly what I’m up to when I write them.”

The habit of thinking and writing about death has left Barnes admirably stoical: “it is now my generation’s turn to die off,” he states matter-of-factly. That generation included Amis and Hitchens as well as Clive James, who died in 2019, and Barnes’s late first wife, the literary agent Pat Kavanagh, who died in 2008. They met in the early Seventies at The New Statesman: Hitchens worked there as a staff writer, Amis was literary editor, and Barnes his deputy. When he wasn’t on television, James contributed book reviews. From the mid-Seventies to the early Eighties, the four of them met weekly in Soho for the now-legendary “Friday lunch”.

As Hitchens wrote in his memoir, Hitch-22 (2010), the Friday lunch was never planned, but “began to simply ‘occur’ … as a sort of end-of-the-week clearing house for gossip and jokes”. Other attendees included the up-and-coming novelist Ian McEwan, the poet James Fenton, the Observer literary editor Terry Kilmartin, the critic Russell Davies, and the elder statesmen Kingsley Amis and Robert Conquest (known affectionately as “Kingers” and “Conkers”). Much was made of this at the time, as Hitchens recounted: “we were believed to ‘control’ a lot of the reviewing space in London, and much envious and paranoid comment was made then, and has been made since, to the effect that we vindicated or confirmed F.R. Leavis’s nightmare of a conspiratorial London literary establishment.” Taking a line from Flaubert, who wrote after the deaths of his friends Louis Bouilhet and Sainte-Beuve that his “little band is diminishing”, Barnes writes in Departure(s): “the ‘little band’ to which I belonged when I came to literary London half a century ago has been thinned over the decades” and is “now beginning to die out”.

There is in this more than one ending: not just the death of each individual writer in turn, but the end of a whole era. Barnes, Amis and Hitchens were part of a new cohort of writers who brought British fiction and criticism out from the tearooms of the Fifties and Sixties and onto the world stage. No generation of novelists and essayists before or since has managed to combine aesthetic and intellectual ambition with outright commercial success in such a way — even the legends of modernism like Joyce and Woolf endured periods of relative obscurity. The vitality and interest of this new cohort’s work was made clear enough in spring 1983, when the literary magazine Granta published a special issue on the “Best of Young British Novelists”, with new fiction from 20 writers, including Amis, Barnes, McEwan, Kazuo Ishiguro, and Salman Rushdie. An accompanying group portrait was taken by Lord Snowdon and published in the Sunday Times Magazine. The photograph is striking: Adam Mars-Jones looking annoyed, Graham Swift impatient to leave, Amis in his school shirt, McEwan dressed like he has already reached retirement age.

As well as their obvious talent and ingenuity, the emergence of the Granta generation was due, in part, to chance: the rapid expansion of the news media throughout the Seventies and Eighties left plenty of space for commissioning young writers and reviewing their newest releases; the growth (in size and esteem) of British universities in general and English departments in particular established a climate of taste for intelligent fiction and criticism; and, fueling both, the 1944 Butler Education Act made state secondary schools free and increased the number of grammar school places. History was on their side: as the former Sunday Times journalist John Walsh describes in his memoir, Circus of Dreams, these were “the baby-boomer generation”, who came of age “in the wild Sixties and felt empowered to do something more creative than join the professions or the financial world”.

Walsh calls this generation “the 1980s literary renaissance” and that phrase is more accurate than you might think. Just as the daubers of Florence in the 14th century were supported and encouraged by the patronage of the Church and wealthy families like the Medici, the literary baby boomers began their careers when Britain’s cultural institutions had clout, energy and money. Newspapers had cash, universities had cash, the Arts Council had cash, so writers had cash. But now we feel some sense of an ending: the money has dried up, the courses have closed and the epochal young writers of the future are too busy working nine to five. All we can hope is that they take early retirement.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe