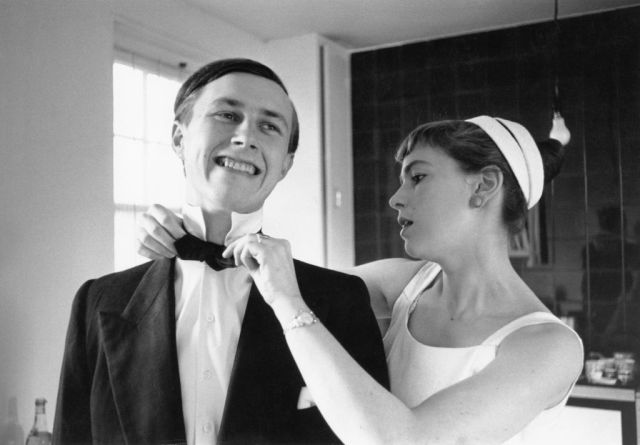

Terence Conran sold a life of tasteful hedonism. Thurston Hopkins/Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

An elegantly dressed woman is polishing her nails, looking into the camera with a kind of feline arrogance. Before her on the dressing table lies a beautiful pair of hairbrushes, while in the background a young man is making the bed, straightening the duvet with a dramatic flick. This photograph appeared in a 1973 catalogue by Habitat, the home furnishing shop founded by Terence Conran. It gives us a sense of the brand’s appeal during its heyday. The room is stylish but comfortable, the scene full of sexual energy. This is a modern couple, the man performing a domestic task while the woman prepares for work. The signature item is the duvet, a concept Habitat introduced to Britain, which stood for both convenience and cosmopolitan style (Conran discovered it in Sweden, and called it a “continental quilt”).

As we mark Habitat’s sixtieth birthday, all of this feels strangely current. Sexual liberation, women’s empowerment and the fashionable status of European culture are still with us. The duvet’s victory is complete: few of us sleep under blankets or eiderdowns. But most familiar is how the Habitat catalogue wove these products and themes into a picture of a desirable life. It turned the home into a stage, a setting for compelling and attractive characters. This is a species of fantasy we now call lifestyle marketing, and we are saturated with it. Today’s brands offer us prefabricated identities, linking together ideals, interests and aesthetic preferences to suggest the kind of person we could be. It was Habitat that taught Britain to think and dream in this way.

The first shop opened on London’s Fulham Road in 1964, a good moment to be reinventing the look and feel of domestic life. New materials and production methods were redefining furniture — that moulded plastic chair with metal legs we sat on at school, for instance, was first designed in 1963. After decades of depression, rationing and austerity, the British were enjoying the fruits of the post-war economic boom, discovering new and enlarged consumer appetites. The boundaries separating art from popular culture were becoming blurred, and Britain’s longstanding suspicion of modern design as lacking in warmth and comfort was giving way. Habitat combined all of these trends to create something new. It took objects with an elevated sense of style and brought them down to the level of consumerism, with aggressive marketing, a steady flow of new products and prices that freshly graduated professionals could afford.

But Habitat was not just selling brightly coloured bistro chairs and enamel coffee pots, paper lampshades and Afghan rugs. It was selling an attitude, a personality, a complete set of quirks and prejudices. Like the precocious young Baby Boomers he catered for, Conran scorned the old-fashioned, the small-minded and suburban. And he offered a seductive alternative: a life of tasteful hedonism, inspired by a more cultured world across the channel. Granted, you would never fully realise that vision, but you could at least buy a small piece of it.

No one has better understood that strand of middle Britain which thinks of itself as possessing a creative streak and an open mind. The Habitat recipe, in one form or another, still caters to it. Modern but classic, stylish but unpretentious, with a dash of the foreign: this basic approach underpins the popularity of brands from Zara Home to Muji. It has proved equally successful in Conran’s other major line of business, restaurants: see Côte, Gail’s Bakery or Carluccio’s (co-founded by Conran’s sister Priscilla). To one degree or another, these brands all try to balance a modicum of refinement with the reassurance that customers won’t feel humiliated when they examine the price tag.

Yet there was always something contradictory about this promise of good taste for the masses. In Britain, influential movements in design have been inspired by a disdain for vulgar, mass-produced goods since the Industrial Revolution. Conran liked to cite the great craftsman and designer William Morris — “have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful” — but Morris famously detested factory-made products. From the Thirties, proponents of modern design despaired at the twee aesthetics and parochial norms of petit-bourgeois life in the suburbs. The fashionable culture of the Swinging Sixties, Conran’s own milieu, likewise defined itself against the conventional majority. This was the era of John Lennon and the Rolling Stones after all.

In his outlook and his commercial ambitions, Conran tried to ignore such tensions: good design should be available to everyone. But they have inevitably come back to the surface. With the rise of Asian manufacturing, passable copies of classy or arty products are now as widespread as any other; think mass-produced ceramics that imitate artisanal imperfection. Similarly, successful Habitat-like brands have acquired corporate managers who force them to expand. Even an apparently exclusive institution such as Soho House, the private members’ club for wealthy creatives, is now a globe-spanning lifestyle brand with locations in dozens of cities and its own line in cosmetics, furniture and workspaces. These trends have made Conran’s vision of life appear increasingly hollow, because even in the absence of snobbery, it relied on a sense of originality, individuality and artistic inspiration. Such qualities are difficult to find when a product suddenly graces every living room and Pinterest board.

These same contradictions doomed Habitat itself. In the late-Eighties, Conran’s appetite got the better of him, and a botched effort to incorporate two other firms led to his ejection from the company. After 2000 the brand rarely made a profit, as it was passed along by a series of retail giants, including Ikea, Argos and Sainsbury’s. Like so much that was fresh and subversive in the Sixties, Habitat was absorbed by the mainstream, its lively identity reduced to a market segment and subject to the demands of accounting. Its famous shops were trimmed down to a handful of showrooms, and last year those closed as well. Today it is little more than the husk of a brand — a slightly upmarket, design-conscious Ikea — condemned to the purgatory of online retail, where every competitor has its endless thumbnail images of seemingly identical products.

A more serious problem is that, while we now have an overabundance of style, the “life” side of the equation has become increasingly sparse. The Boomers buying continental quilts were a generation on the up. They could plausibly imagine themselves moving towards the spacious and leisurely domestic life that Conran dangled before them. Most of those young professionals who entered work after 2008, by contrast, know they will never stack their French crockery in a French holiday home; they would be happy with a modestly sized apartment. So aspiration does not really capture the appeal of lifestyle consumerism for these embittered millennials. It is more a question of consolation, or escapism, or a desperate attempt to distinguish themselves from the mass market where they know they belong.

Then again, it increasingly feels like the whole notion of lifestyle was a recipe for dissatisfaction to begin with. Habitat emerged at a moment when traditional roles and social expectations were melting away; in their place, it proposed the idea of life as a work of art, an exercise in self-fashioning, with commodities and experiences guiding consumers towards a particular model of themselves. Today, with all the niches and subcultures spawned by network technology, there is no shortage of such identities on offer. If you like outdoor activities, you may find a brand community that combines this with certain political views and a style of fashion. If you like high-end cars, you might dream of occupying a branded condo in Miami or Dubai.

But these lives assembled from images remain just that: a collection of images, a fiction that can never fully be inhabited. It seems the best we can do is represent them in the same way they were presented to us, as a series of vignettes on Instagram, where the world takes on a idealised quality that is eerily reminiscent of those Habitat catalogues from decades ago. One gets the impression that we are not trying to persuade others of their reality so much as ourselves.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe