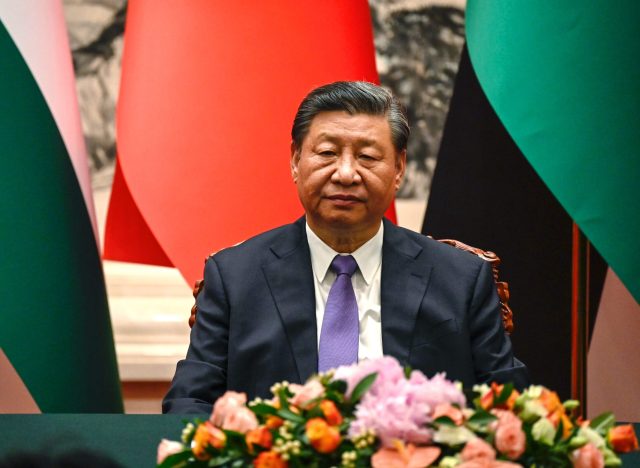

Destined to remain the Middle Kingdom (Jade Gao – Pool/Getty Images)

You wouldn’t have guessed from Narendra Modi’s beaming smile after the G20 last weekend that the global economy was running out of steam. The latest IMF forecast projects it to expand by 3% this year, down from the 3.5% anticipated earlier this year. But while this might worry leaders of the world’s richest economies, from where Modi stands, things are looking pretty rosy.

The global growth rate is being dragged down by the big beasts, namely the G7 countries and China — but elsewhere things are looking up. Modi’s India is humming along at more than 6% a year, with Indonesia close on its heels. While there are still laggards in the developing world, such as South Africa, other perpetual slow-growers including Mexico and Brazil are now coming up strong. Significantly, this growth is generally being engineered amid fairly conservative fiscal conditions, suggesting that expansions will have a better chance of becoming sustainable.

The same cannot be said of the world’s largest economies. There is much excitement in the US about Joe Biden’s green transformation programme, but it is not yet clear if this debt-fuelled boost will outlast the spending spree. In fact, once one strips new debt from new growth, the G7 economies are close to flatlining. They would have collapsed altogether during the pandemic had it not been for their governments borrowing trillions to keep them afloat — something that can’t be said of most developing countries, which weathered the storm fairly well. In this state, the ageing and debt-saddled West will struggle to restart its economic engines.

This seems to be the direction in which China is headed as well. An alleged Chinese spy at the heart of Westminster may have captured the media’s attention this week, but Beijing’s bigger story is one of diminishment. While it may sound impressive, China’s growth rate of more than 5% is significantly less than what its leadership had expected. Moreover, given China’s heavy reliance on debt to keep boosting its economy, it’s not even clear how much of China’s expansion can count as growth. With its population ageing rapidly, the Middle Kingdom’s dream of one day resuming its historic place as the world’s largest economy now looks to be in jeopardy.

If there is spirited debate among economists as to whether China will be able to escape its funk, there is broad agreement about how it sank into it. Over the last 40 years, and particularly in the two decades straddling the turn of the millennium, China built its economy by exploiting its massive labour force. By repressing wages so as to attract investment in the manufacturing of goods wanted by the rest of the world, it was able to allocate nearly half its economic output to investment. The result was an unprecedented buildup of a world-class industrial base.

There are obvious limits to this strategy. Eventually, the world gets tired of being a sink for one country’s output. Overseas markets were saturated by “Made in China” goods and recent moves in China’s trading partners have put a crimp in its ability to keep exporting its way towards growth. In the US, for instance, the Biden administration has largely continued with its predecessor’s attempt to reduce trade with China, and even though Europe won’t go so far, talk is growing of the need to “de-risk” trade. As a result, China has reached the mature phase in its development; now it has to shift from an investment-based model towards a consumption-based one — in which rising incomes enable more of the economy’s output to be consumed locally.

On the face of it, this shouldn’t be difficult to achieve. One of the reasons that China’s saving rate is so high — some 45% compared to a G7 average of half of that — is that it does not have the sort of welfare state that exists in Western countries. As a result, Chinese households build up large rainy-day funds, storing much of it in real estate, which only adds to the country’s economic woes since it further inflates the housing bubble that has so worried the government. In addition to direct transfers of money to boost consumption, such as stimulus cheques, the Chinese state could encourage its citizens to spend more by providing them with the sort of healthcare that removed the necessity to self-insure to such an extent. If Chinese families knew they could rely on state care to cover a long-term illness, they might not feel the need to squirrel away so much of their earnings.

That, however, is proving to be an obstacle for the ruling Communist Party. Part of the resistance to changing its economic strategy is ideological: Xi Jinping frequently muses that welfare will sap Chinese resilience. But part of it is practical. China has the administrative infrastructure needed for big public investment programmes, from building housing blocks to high-speed railway lines, but lacks the capacity for a similar ambition in delivering services to their citizens. When faced with an economic slowdown, the Chinese authorities keep doing what they do best — borrowing tons of money to fuel yet more big public works programmes. But the problem is that these merely add new capacity to an economy that already has too much of it, leaving the country with even heavier debts in the meantime.

China’s economic woes are part of a wider global trend. The two-track world economy, in which the big powers are slowing and the rising ones are catching up, began to take shape in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, and it seems to have ossified since the pandemic. It was only a matter of time before the consequent economic redistribution began to alter the geopolitical landscape. Although Western observers still tend to see the world through Cold War lenses, merely substituting China for the old Soviet Union as the opposite pole in the global political economy, the emerging world order is actually a lot more complicated.

Along with the recent Brics Summit in South Africa, the G20 revealed a more assertive developing world that is less willing to sing superpower tunes. If India and other developing countries — including the African Union, which secured a permanent seat at the table of what will now become the G21 — feel they got what they wanted out of the Summit, the same probably can’t be said of the US, China, or Russia. While the final declaration on the war in Ukraine didn’t deliver the condemnation that the Western allies had wanted, it didn’t exactly leave Russia off the hook, regardless of what Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov would have us believe.

The same was true at the Brics summit a few weeks ago. Widely seen as a success for its South African host, Russia tried but failed to enlist support there for its position and ended up looking somewhat isolated. Countries such as India are quite happy to buy Russia’s oil and natural gas at the knock-down prices resulting from sanctions, but they’re not going to line up in its camp. As for China, Xi sat out the G20 Summit, probably as a snub to his Indian rival, only to watch as it produced a blueprint for a trade corridor between Europe and Asia that will rival China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Xi has long wanted to position himself as the head of a rising world; Modi may have exploited his absence to take his place.

What all this reveals is a range of rising middle powers that will pick and choose from what the major powers have to offer, whether it be trade concessions or aid, without offering them blanket support. India not only won the African Union a seat at the table but also engineered language favourable to the multilateralism and World Bank reform it favours. Rather than a world which is polarising into two camps, therefore, what we are witnessing is a world in which middle powers are skillfully playing the US, China, Russia, and Europe off against each other, securing concessions from all as each of the superpowers tries to curry favour with as many of them as possible.

Meanwhile, something interesting is going on in the background. To say that big economies are floundering obscures the fact that for many people, their individual circumstances may be turning a corner. In Western countries, house and share prices have been falling in real terms, but real wages have, after decades of stagnation, recently turned positive. It will take a while before people begin to feel the cost-of-living crisis is receding, but there are reasons to believe that reversal may prove permanent. After decades of rapid expansion, the growth of the global labour supply has begun slowing. The consequent rise in labour’s bargaining power has shown up in recent pay settlements across the developed world, where competition to attract immigrant workers will get more fierce.

In short, while the world economy slows, the poor get richer and the rich stand by. Not only is the developing world’s share of global income rising, but within Western countries, the share of income that goes to labour looks set to rise too. If this is what the end of growth looks like, many could be forgiven for saying “bring it on”.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe