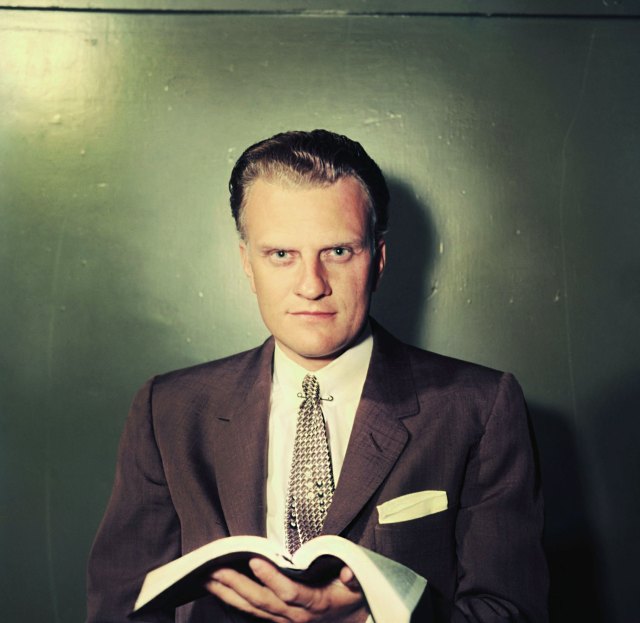

His vision remains a fantasy (Getty)

There was a time when evangelical Christians were peace-making unifiers in American politics: an era that produced the closest thing to a Protestant saint the nation has ever seen. Billy Graham’s mass appeal stemmed in part from his aversion to partisan politics. The Southern Baptist minister is estimated to have preached to over 215 million people, and enjoyed personal audiences with 12 consecutive US presidents, from Harry Truman to Barack Obama, advising them on religious matters regardless of which party they represented.

During that span, Billy’s interventions in politics were purposely few (although he did openly support Richard Nixon over Roman Catholic John Kennedy). Above all, his priority was to remain neutral, so as to alienate none and reach many. His biographer Grant Wacker described him as the “Great Legitimator”, noting that Billy’s mere “presence conferred status on presidents, acceptability on wars, shame on racial prejudice, desirability on decency, dishonour on indecency”.

Billy died, at the age of 99, in February 2018, but he lived long enough to see his good work vanish. His ministry, the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA), is now ruled by his Trump-supporting, loud-mouthed, rabidly partisan son, Franklin Graham, whose name is synonymous with controversy in the United States — and, more recently, in the UK. The difference between these two men reflects how American evangelical Christianity has, like American politics, evolved — becoming more fractured and polarised.

Billy was the product of the consensus-building Fifties, when church attendance in the United States was actually rising and the battle for souls and donations, like the struggle against international Communism, was waged across party lines. An heir to the rambunctious, revivalist free-market tradition in American religion (the country has never had an established church, and the last state to financially support the Episcopalian church ceased funding it in 1833), Graham followed the example of the great 19th century evangelists, Charles Grandison Finney and Dwight Moody. Both leapt on the technologies of their time — handbills and large outdoor revivals — to draw large followings; Billy had radio and television at his disposal.

Franklin, by contrast, is a child of the late Seventies, when church attendance had begun to dip, and evangelicals became more radical. Young ministers such as Moral Majority leader Jerry Falwell and televangelist Oral Roberts had begun to organise fierce opposition to the 1973 Supreme Court decision that women had a fundamental right to choose. It was opposition that increasingly aligned them — and their small but politically active congregations — with the interests of the Republican Party.

It’s not that Billy was uncontroversial. But his most talked-about interventions were always for the sake of unity, rather than division. Although a moderate in most respects, Billy, a native of largely conservative North Carolina, made waves during the late Fifties for welcoming black and white people alike to his revival events, at a time when many public venues in the American South were legally segregated. He also encouraged mainstream Protestants — Methodists, Episcopalians, Presbyterians — to remain within their churches even after they absorbed his message of “accepting Jesus Christ as your personal saviour”. Knowing that curious “inquirers” would return to their churches with renewed enthusiasm, the leaders of these denominations were always happy to partner with Graham’s “crusade counsellors”, to promote his events and boost his attendance figures. Graham wanted to reach listeners, not sow discord within American Protestantism.

Most tellingly of all, Billy refused to join with ultra-conservative religious figures such as Falwell. He had no wish to tie BGEA to the culture wars of the Religious Right. If he ever lapsed into expressing the kind of social conservatism that the Christian Broadcasting Network might champion, he hurriedly recanted. After commenting in 1993 at a religious event in Ohio that AIDS might be a “judgment of God”, Billy retracted his words, stating a few days later that “to say God has judged people with AIDS would be very wrong and very cruel”. One of the myths about tolerance in America, tied to the myth of moral progress so popular here, is that the past is always benighted and bigoted compared to today. The story of evangelicalism in the United States, which played a key part in the abolition of slavery in the 19th century and women’s suffrage in the early 20th, proves otherwise. Billy Graham, in fact, represents the high-water mark for evangelical tolerance. His intolerant son has made sure of it.

Unlike Billy, who graduated from Wheaton College in Illinois — considered the “Harvard of American evangelicalism” — and proceeded almost immediately into a star-studded career in preaching, Franklin took a more circuitous path to success. He dropped out of a Christian private school, and was later expelled from a small Christian college for staying out past curfew with a female classmate. After he finally graduated, instead of immediately working for BGEA, he became the president of Samaritan’s Purse, an evangelical Christian aid organisation. There, he came into his own as a prolific fundraiser.

A morally unimpeachable, thoughtful theologian he was not. But Franklin was representative of a new kind of Christian leader: the born-again crusader who could galvanise his own flock without building bridges outside of it. The parallels with politics are uncanny: where once Democrats and Republicans had fought for the voters in the centre, the stars of both parties have become more ideological and less accommodating since the turn of the millennium. Elections have increasingly favoured hardliners and zealots over bipartisan cooperators.

When, in 2000, Franklin was finally appointed CEO of BGEA, he wasted little time moving the organisation in a direction more consistent with the work of his contemporaries on the Religious Right. Billy Graham could win souls by the millions, but he could not secure Congressional votes by the dozens; younger evangelical leaders such as Jerry Falwell and Ralph Reed could, thanks to their hand-in-glove relationship with the Republican Party. As political science professor John Hicks wrote in 1996, this was a strategic decision with profound consequences: it gave evangelicals access to a network of support to influence elections and public policy decisions.

Franklin, however, thrived by continually provoking clickbait headlines. Following the 9/11 attacks, he declared that Islam was “a very evil and wicked religion”, and supported the resulting war in Iraq. Where his father might have recanted, Franklin doubled down in the face of criticism from more mainstream religious leaders, who pressured the Army into disinviting him from its National Day of Prayer at the Pentagon in 2010. “True Islam can’t be practiced [in the United States],” he told CNN in 2009, “because you can’t beat your wife or murder your children.” When asked by CNN in 2010 about Barack Obama’s religious background, he replied that “the president’s problem is that he was a born a Muslim”.

In a 2005 interview about his son’s provocative comments, Billy made it clear that he didn’t approve: “Let’s say, I didn’t say it.” But he didn’t face the same challenges as his son. It is growing secularism that explains Franklin Graham’s shift away from his father’s nonpartisan approach. Like any actor in the marketplace of ideas, Franklin is keenly aware that his market, unlike his father’s, is shrinking. The religiously unaffiliated, or the “unchurched”, now account for a quarter of all Americans — a trend noted in Robert Putnam’s seminal work Bowling Alone, and which has only intensified in the past half-decade. Nowadays, 27% of Americans describe themselves as “spiritual but not religious”, and another 18% as “neither religious nor spiritual”. Aware of the partisan nature of his support and increasingly unable to grow the size of his flock, Franklin needed to motivate those who remained to donate, advocate, and vote on his behalf.

And so, he leaned into his divisiveness. In 2014, he — like Pat Buchanan, Rod Dreher, and a number of other American conservative leaders — praised Russian President Vladimir Putin for passing tough anti-gay legislation. More recently, he publicly chastised openly gay Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg during his 2020 presidential campaign. The same year, despite growing racial diversity among American evangelical Christians, he denounced Black Lives Matter and posted on Facebook that police shootings could be avoided through “respect for obedience and authority”. His followers, who back most of the same policies he does to a greater or lesser degree, recognise that Franklin speaks for them. If anyone doesn’t, Franklin told The Atlantic in 2017, they can “talk to God about it”.

His rhetoric, and appeal, is Trumpian. So it’s hardly surprising that Franklin explains in the same interview why he chose to hitch BGEA’s fortunes to those of Trump: “He did everything wrong… and he became president of the United States.” There’s “no question,” for Franklin, that God must therefore have been supporting Trump, a much-needed “Christian voice in office”. Throughout the ex-President’s two campaigns for office, Franklin included a few minutes of political material in each of his sermons, often opening by discussing how abortion is murder, how same-sex marriage is a sin, and, most importantly, how the increase in secularism will result in godless Communism.

Recent research has found that the increasing percentage of Americans who identify as atheist or agnostic do indeed have a clear political affiliation: they make up 20.6% of Democrats, up from 11.8% in 2008. (In Republican ranks they constitute a mere 4% now, up slightly from 3.3% in 2008.) Not only that, but these atheists and agnostics are more likely than evangelicals to donate to political campaigns, attend political meetings, put up political signs, and attend political protests. Billy Graham devoted his entire career to pulling such people back into the fold. Franklin, by contrast, has focused on maximising the value of the devout audience he has left — even as Republican politicians focus on preaching to the converted rather than reaching across the aisle.

On Saturday, Franklin tweeted: “I loved this country, and I cannot vote for candidates or the party that supports abortion, defunding our police, or open borders.” In today’s midterms, many “too-close-to-call-elections” could turn on votes from either the Religious Right, who would agree whole-heartedly with this sentiment, or the growing minority of unchurched, who are likely to be disgusted by it. The irreconcilability of these two groups warns of further polarisation downstream. But some thinkers, such as Harvard Law Professor Adrian Vermeule, have argued that religion could again have a unifying role in the future of the American polity. It would take a great unifier like Billy Graham, not a sectarian divider, to achieve such a lofty goal. For now, American Protestantism, once considered the ecumenical moral bedrock of the nation, is diminished and enmeshed in party politics — and the America bound together by “common things”, for which Billy Graham so earnestly preached, remains an unrealisable fantasy.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe