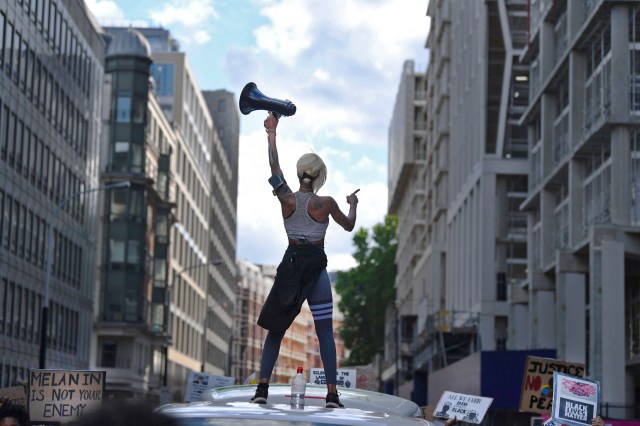

When is solidarity phoney? Credit: Kerem Yucel/AFP/Getty

Fin de siècle Europe was big on human zoos. From the 1870s to the 1920s, Antwerp, Paris, Barcelona, London and Milan all featured at least one. In 1900, the Austrian poet and heartthrob Rainer Maria Rilke visited a human zoo in Zürich and was sorely disappointed. The West Africans trafficked and put on exhibition were not savage enough for his taste.

Rilke’s poem “Die Aschanti,” about his visit to the exhibition, is characterised by sadness. In the exhibition, he writes, there are “no brown girls who stretched out / velvety in tropical exhaustion,” “no eyes which blaze like weapons” and no mouths “broad with laughter”. What a bummer. Rilke has to settle for ordinary, human and fundamentally inauthentic Africans: “O how much truer are the animals / that pace up and down in steel grids”.

The Nigerian-American novelist Teju Cole studies Rilke’s attitude to human zoos in his essay “The Blackness of Panther.” Its title is partly annexed from a more famous Rilke poem, “The Panther”, about big cats behind bars in Paris. Cole draws a parallel between the panther, or the captured African in a human zoo, and the way the African is perceived more generally amongst a segment of Western society. Like the new collection it is part of, Black Paper (released last week), it examines what it means to be an African person in a world shaped by white people’s cultural norms.

Cole finds the codes associated with it to be restrictive. “Was I African?” he asks in one passage, about growing up in Nigeria, because “I didn’t feel it. What I felt was that I was a Lagos boy, a speaker of Yoruba, a citizen of Nigeria”.

“The Africans were those other people,” he writes, “some of whom I read about in books, or had seen wearing tribal costumes in magazines, or encountered in weird fictional form in movies”. He does not see his reflection in them. The label, then, is a fiction imposed on him by western culture.

Cole is more sympathetic to the general term “Black”, but even here he acknowledges how rooted it is in one singular definition. The label “Black” was not “about every Black person in the world”, he writes, but “it was localized to the American situation. To be Black in America, that localized tenor of ‘Black’ had to be learned”. Having a “Black skin (sometimes just a shade or two off-white) was the admission to the classroom, but Black American cultural codes were the lesson”. Cole writes that he has learned to love the codes, since moving to America over twenty years ago, while acknowledging that “it wasn’t the only Black” that he knew.

These are quandaries that have recently been explored by another, perhaps less well-known, novelist who grew up in Nigeria and later studied in America. Timothy Ogene’s new novel Seesaw (out next week), set in the very recent past, is a playful and lacerating satire on the codes the black immigrant needs to satisfy in order to curry favour with a self-styled progressive institution in America.

Frank Jasper, the protagonist and narrator, is a failed novelist from the fictional southern Nigerian city of Port Jumbo, based on Ogene’s home town Port Harcourt. Ogene’s first novel, The Day Ends Like Any Day, has a similar title with Jasper’s first novel The Day They Came for Dan. But unlike Ogene’s novel, which won the Book of the Year award with the African Literary Association, Jasper’s novel does so badly that he decides to write a review of it under a pseudonym for an obscure website entitled The Ganges Review of Books. Very soon after this appreciative review goes up, the website completely disappears in favour of a screen selling viagra.

Jasper’s big break comes in the form of the William Blake Program for Emerging Writers, which allows him to travel to a New England college town and get mentored by other writers. When he arrives, he is bemused by protests he encounters on campus. They don’t fit with his conception of American radicalism. “My idea of an American radical protest,” he writes, “was ossified and romantic, involving pictures of people in long hair smoking marijuanna, playing drums and banjos”. What he witnesses instead are protestors that “might as well have been business executives, clear-eyed with state-of-the-art digital equipment”. In other words, the self-styled revolutionary vanguard of progressive institutions have become much like the old-school establishment of old.

On campus, Jasper also meets a fellow African writer Barongo Akello Kabumba, who is from Uganda. And a British-Indian academic called Sara Chakraborty, who grew “up in Surrey as the grandchild of Afro-Asian immigrants”. He takes a strong dislike to the pair:

“partly because I didn’t understand the depth of their moral authority, the immutable authority with which they said things about the world and people and identity and the ‘post-colonial world’ in a few days than in all the years I lived in it”.

Their conception of the “post-colonial” world, and the position of Africans within it, is sterile and monolithic: Jasper’s post-colonial world “was nothing like the fully formed and footnoted gunfire sentences I heard from Sara Chakraborty, nothing like the costumed performers of the Ugandan writer”. Instead, it “was just another tired world of complicated people trudging along, like anywhere else, mostly oblivious of life beyond their neighbourhood, full of pain or courting happiness, vile or honest”.

Underpinning that passage is a plea for moral universalism: for seeing that, despite their differences, the post-colonial world is fundamentally as emotionally rich and also as boring as the Western world. And Ogene demonstrates this very combination in the novel itself. Apart from the zestful humour in the narrative, there is also tedium. In the passages set in Nigeria, for instance, Jasper is a slacker par excellence, who spends much of his recreational time taking drugs and watching pornography. The novel reminds me not only of post-colonial novels, or campus novels, but also of the decadent novels of Michel Houellebecq, in which a buoyantly satirical attitude to twentieth-century Western society is combined with hardened cynicism.

And Jasper is a thoroughly cynical character. While acknowledging the silliness of race experts, those who tell guilt-ridden white people what they want to hear, he occupies the position of black expert to his advantage. He was “still in the US when” his agent

“sold me to the Montana-based group as an ‘understanding expert on all matters black and ethnic’. He had played up my background as a ‘son of the black Atlantic whose maternal ancestors were descendants of slaves who came back to West Africa’”.

He adds with acidic scorn: “if Americans were going to devour themselves, he said to me afterwards, someone might as well hide under the table for crumbs”. This cheerfully parasitic attitude is not one that Cole explicitly argues for in his essays, which are scrupulously analytical. But it does demonstrate that the analogy of the human zoo, while powerful, fails to capture the symbiotic relationship between the patronising white person and the African. To put it bluntly: it’s a grift that seems to satisfy both parties. The Africans at the zoo were forcibly captured; the African novelist freely moves to the West.

Jasper’s relationship to his status as a race expert is, however, ambivalent: while it materially enriches him, it also deforms his humanity. “I wasn’t advancing any single ideology,” he considers, “or worldview or notion of progress, and wasn’t trying to attack anyone”. Rather,

“I just wanted to exist and cry and laugh and fuck and live and die without prefixing or suffixing my actions with any universal idea of blackness or Africaness or whatever thing out there I was supposedly tied to as a POC or BAME or warped extension of someone else’s imagination”.

This warped tendency doesn’t just apply to black people. Other ethnicities feel it too. In an interview with Lauren Oyler, the Argentinian novelist Pola Oloixarac talks about the inspiration for her latest novel, Mona, which is out in the UK next year. “I was a person of colour when I was in the US,” she says, but “if I took a plane and went anywhere else, or if I crossed the border I wasn’t a person of colour anymore. So it wasn’t an essential trait. It was more of a particular fiction that was imposed on me”.

The titular protagonist of the novel is Peruvian and, like Jasper, is already the author of one novel and living in an American college campus:

“Mona had arrived at Stanford not long after the waves she made with her debut novel tossed her onto the beach of a certain impetuous prestige — and at a time when being a ‘woman of colour’” began to “confer a chic sort of cultural capital”.

The narrator of Oloixarac’s deliciously acerbic novel adds that, again invoking our opening analogy, “American universities shared certain essential values with historic zoos, where diversity was a mark of attraction and distinction”.

When Mona is nominated for a prestigious literary prize in Europe, she travels to Sweden, where she meets a diverse range of writers, whose background she anatomises like a modern-day Carl Linnaeus (the pioneering Swedish taxonomist). There is the obnoxious French male writer, the pious Israeli female author, the sexy Scandinavian writers. There is a sense that she is trapped by the instinct to perceive these characters solely through the prism of their identity. And a part of the narrative tension is this tendency against a countervailing emphasis on a person’s particular experiences. She chafes at being seen as the “Latin writer”: “The phony solidarity of having a ‘Latin’ culture in common with other writers was something that always repulsed her”.

She recognises, like Jasper and Cole, that such labels do not reflect the humanity of an individual. While they can breed important forms of solidarity, and can be useful in analysing prejudice and discrimination, we shouldn’t cling to them too tightly. It is ironic that many self-styled progressives, many of them well-intentioned, do so. It illustrates the comfort, under a progressive guise, that comes with being attached to racial essentialism: the comfort of expecting people from other racial or ethnic backgrounds to fulfil a role.

Labels should be used, if they are to be used, as the start of someone’s identity, not the full definition of it. They should be used to open the doors to a deeper understanding of who that person is, rather than perceived as the only thing that matters. The alternative is race representatives, people who are exhibited, or exhibit themselves, to a white audience, to be gawked at and cuddled, and are expected to possess a morality befitting a child.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe