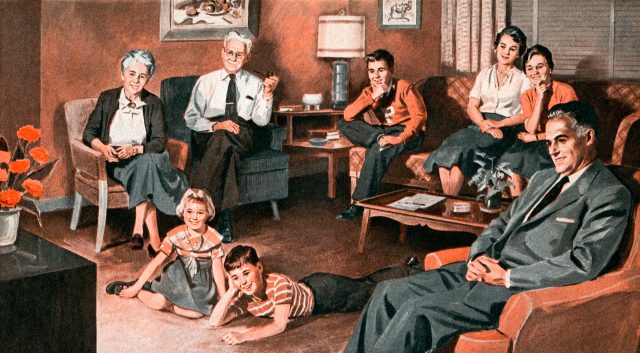

This way madness lies. Credit: GraphicaArtis/Getty Images

In the last year and a half, many in the West have learnt that being locked up for long enough can make you nuts. A related but more venerable truth is that being nuts for long enough can get you locked up. In 1968, Frederick Exley, a 39-year-old American no one had ever heard of, published a hilarious and disgusting autobiographical novel about this second truth. Its world of forced isolation and surveilled intimacy is recognisable as our own.

A Fan’s Notes describes Exley’s “dizzying descent into bumhood”. Witty, handsome, athletic, a graduate of the University of Southern California burning with ambition to write, Exley found himself unable to stop drinking, unable to hold down lucrative public-relations jobs at railroads and missile manufacturers, and unable to rouse himself from his mother’s “davenport” (a quaint American term for a sofa bed) where he sat watching soap operas and eating Oreos by the box. As a result he spent two stints in a mental institution he calls “Avalon Valley”, where he was subjected to insulin shock and electroshock treatments.

Exley’s book is partly a metaphysical conceit of the United States as a giant loony bin. “I believed I could live out my life at Avalon Valley,” he wrote, “live it there as well as live it in any America I had yet discovered.” With a common American provincialism, he often uses “America” to mean “the human condition” or “my state of mind.” Unable to connect with a girl he loves, he decides that “my inability to couple had not been with her but with some aspect of America with which I could not have lived successfully.”

Exley is ambitious to the point of megalomania. “Knowing nothing about writing,” he recalls, “I had no trouble seeing myself famous.” But he is lazy — and, when he conquers his laziness, perverse. He redeems himself by writing a vast and ambitious work over an obsessive year, and then, in a moment of drunken frustration, throws it into a furnace.

While his USC contemporary, the football star Frank Gifford, became a model of manliness to his fellow countrymen, Exley came to think he was destined merely “to sit in the stands with most men and acclaim others. It was my fate, my destiny, my end, to be a fan”. Exley would wind up more than that, and partly out of luck. He was a misfit oppressed by the America of Hiroshima and McCarthy, but his book was published in the America of Haight-Ashbury and Woodstock. It wound up beloved of William Styron, John Cheever, Nick Hornby and pretty much any male writer born before the year 1980.

In light of present-day medical knowledge, A Fan’s Notes can be seen as a book about alcoholism. Everything in it derives from booze: the metaphysics, the moods, the hallucinations, the ambitions, the scrapes. Exley does not reflect on the ethics of the arms trade, say, and then leave his cushy PR job. No: He gets fired from his job for drinking and then lashes out — always saving his worst cruelty for those he resents having to accept charity from. When his mother expresses horror that a family acquaintance has been arrested for the statutory rape of a fourteen-year-old girl, he replies: “Lovely age, fourteen.” His fantasies are violent, sometimes even murderous, and frequently pornographic.

Exley is a broken and occasionally misogynistic man. “The world of the soap opera,” he reflects, after months of watching them on his mother’s TV, “is the world of the Emancipated American Woman, a creature whose idleness is employed to no other purpose than creating mischief.” But it would be a mistake to ascribe Exley’s misogyny only to his brokenness. The book’s political incorrectness is more in what he observes than in what he believes. It was written in the Age of Freud, with its dogma that bringing everything to the surface is best, embarrassing though it may be.

Exley introduces us to Mr. Blue, a mythomaniac aluminium-siding salesman obsessed with calisthenics and cunnilingus. “I was immensely fond of the pussy-bedazzled old bastard,” the author recalls, “biases, bullshit, and all…” His own rich and sadistic brother-in-law Bunny, who probably possesses the first television-equipped “man cave” in Western literature, speeds along the roads of northern Westchester County with a car full of shotguns, drinking beer out of a cardboard cup and looking for stray cats to blast, his conversation a “tornado of monstrous smut”.

Exley’s society has a texture that will call to mind the society of the Covid lockdown: there are certainly interesting characters in it, like Mr. Blue, Bunny, and Exley himself, but they are never really “out in the world”, making commitments and forging relationships. They are sidelined solipsists, perhaps exposed to the same events and stimuli, but each living them in isolation, not as part of a community — and this is as true in bar rooms as it is in insane asylums: “The patrons of Louis’ did not like each other very much,” Exley recalls of one literary haunt. “It is only now that I can see that we represented to one another wasted time and crippling dreams.”

Post-lockdown may recognise the truth in another insight of Exley’s: because time moves, and because we are mortal, it is never really the case that “nothing is happening”, or that we are “doing nothing”. There is almost no place in the United States more remote (“steppelike” is Exley’s word) than Watertown, New York, where Exley idled away the last years of the Eisenhower administration on his mother’s davenport. Yet this was somehow an active idling. The time was needed so that “one man might make his peace with a new and different man… I then believed that nothing whatever was at work, that I was drifting quite aimlessly on a davenport, when in fact that davenport was taking me on an unwavering, rousing, and often melancholy journey.”

Television looms over Exley’s life with a force analogous to that of alcohol. He recognises “its deceit, its outright lies, its spinelessness, its weak-mindedness, its pointless violence,” yet he needs it for sleep. Exley was ahead of his time. Today everyone has some kind of love-hate relationship with TV, and one of the West’s great cultural contradictions involves mediation. Media, in the Burkean sense of small institutions, make possible a democratic society by buffering controversies.

But media, in the McLuhanesque sense of opinion-organisers, undermine that democracy by grooming citizens ideologically and then isolating them from one another. The star-fan relationship and the commissar-subject relationship replace the mentor-student relationship and the friend-friend relationship. In the 1950s, the United States was the only country where television had developed this way, and only a minority of adults had developed the pathological relationship to it that Exley had. Over time, the rest of the world has grown more American, more Exleyesque, and Covid has given this world another fillip.

Exley built an extraordinary set of virtues appropriate to his hard-luck state. Those virtues often saw him through, even if — rather like The Band, or the Republic of Ireland — he was unable to maintain them in the face of success and relative enrichment. He wrote two more books that sold poorly and failed to excite critics. Still, A Fan’s Notes remains a brilliant reminder, in a trapped and desperate time, that life goes on, even when it appears to have stopped. “That the fear of death still owns me,” Exley writes, “is, in its way, a beginning.”

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe