The founder of secularism

Perhaps the most extraordinary cultural transformation in Britain over the past half-century is the decline of Christianity. Two generations ago, two-thirds of the country identified as Christian; fewer than 40% now do. Only 12% of British people now identify as Anglican — the state religion of the country. Only 1% of 18 to 24 year olds are Anglicans.

In America, the picture seems more rosy. 65% of Americans identify as Christian. But ten years ago the figure was around 75%. And in the early 1980s it was close to 90%. The trajectory is clear.

There is, of course, a distinction between identifying as a Christian and going to church every week. On the latter front the picture in Western Europe is strikingly bleak. As Harriet Sherwood puts it in the Guardian: “In the UK, France, Belgium, Spain and the Netherlands, between 56% and 60% said they never go to church, and between 63% and 66% said they never pray”. But what interests me more is disaffiliation — the lack of willingness to espouse even a Christian identity.

This is secularisation: the transformation of religion from an integral part of civic life to a fading husk. The relationship between Christianity and secularisation, framed this way, looks antagonistic. Secularisation is Christianity’s bête noire.

David Lloyd Dusenbury’s new book, The Innocence of Pontius Pilate, investigates the relationship between Christianity and the secular. And he comes to a radically different conclusion. Rather than viewing them as conflicting poles, Dusenbury argues that the secular is a product of Christian thinking.

This viewpoint, or something very similar to it, is advanced in Larry Siedentop’s Inventing the Individual, Tom Holland’s Dominion, Nick Spencer’s The Evolution of the West, and many works by John Gray. I don’t think Sam Harris and Richard Dawkins are fans of this view.

Secularity, he writes, doesn’t come “from a priest-baiting eighteenth-century philosophe”. Rather, “it is a coinage of medieval Christian writers”.

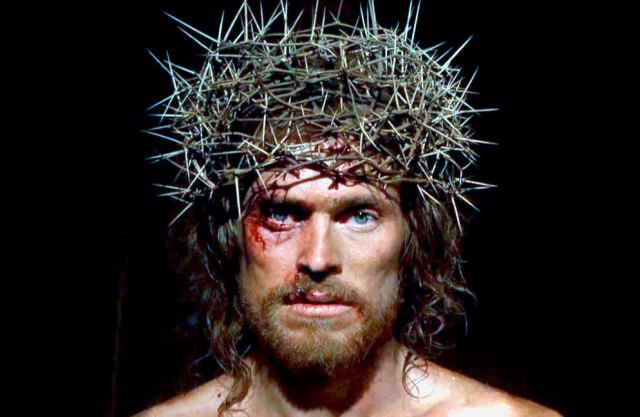

To substantiate his thesis, Dusenbury goes further back than medieval Europe to the most consequential legal judgement in the history of western civilisation: the Roman trial of Jesus.

When we think of secular, we immediately conceive it in terms of the privatisation of religious belief. Properly speaking, the secularist would say, religion does not belong in the public sphere. But a more fundamental distinction is between the temporal and the divine: what is secular is the distinction between the laws of man and the laws of God.

What constitutes the secular, in this frame, owes much to an utterance made by Jesus in the Gospel of John. As he is tried and convicted by Pontius Pilate, Jesus proclaims: “My kingdom is not of this world”.

This still seems abstract. How does that allusive proclamation lead to a greater limit of religion’s role in society? A famously doctrinaire bishop in an African port city is the first person to edge us towards our modern conception of the secular: Augustine of Hippo.

Augustine’s Homilies on the Gospel of John is crucial for understanding the secular. Augustine insists on the guilt of Pilate in the trial of Jesus. And he contrastingly affirms the innocence of Christ. Augustine, writes Dusenbury, is thus “led… to theorise the reign of God and the kingship of Jesus in a way that radically contrasts them with the ‘reign’ of any human empire and the ‘kingship’ of any human sovereign”.

When Augustine examines Jesus’s statement “my kingdom is not of this world”, according to Dusenbury, “he hears a delineation, by Jesus, of a novel form of jurisdiction that renders all other forms of jurisdiction, eo ipso, worldly — which is to say, secular”. Most human judgements are, according to Augustine, “melancholy and lamentable”.

This means “they derive not only from human laws and insights but from human ignorance and prejudice”. Human laws are provisional and subject to the failures and biases of human reasoning. By contrast, the law of the Lord is perfect.

Another Roman African, Pope Gelasius, substantiated this distinction in the late 5th century when he proclaimed in Latin duo sont. This means: “there are two”. The laws of Caesar are distinct from the laws of Christ. According to Gelasius, “no Caesar is competent to clarify the ‘venerable mysteries’ that are celebrated, and promulgated, by the church”.

Ultimately, writes Dusenbury, “it is the African prelates Augustine and Gelasius, I believe, who transmit to medieval clerics and legal theorists in Europe a lexicon of ‘secular power’, and an interpretation of the Roman trial of Jesus that will be cited and reconceived, between the fourteenth and the eighteenth centuries, in continent-shaping ways”.

How is this interpretation of what is secular seen in the early modern period? This was the time when our modern notion of toleration was first thoroughly systemised. Hobbes, according to Dusenbury, argued that the “Ecclesiastics ‘have not Regal Power in this world’, Hobbes writes, for the simple reason that ‘the Kingdom of Christ is not of this world’. It is only because of this – which is to say, because of the Roman trial of Jesus – that Hobbes can definitively state that ‘Faith hath no relation to, nor dependence at all upon Compulsion’”.

Because the law of God has no jurisdiction in the world of man, people should not be compelled to subscribe to religious doctrine. The case for identifying with Christianity thus rests on the persuasive power of Christian doctrine itself.

Dusenbury also examines Samuel von Pufendorf’s interpretation of the trial of Jesus in light of secular power. Pufendorf, little read now, is according to Dusenbury “Locke’s rival in forging the modern logic of toleration”. Jesus, according to Pufendorf, is a king but “his kingdom is not of this world. A correct reading of the Roman trial of Jesus is thus, according to Pufendorf, a sine qua non of a European political culture in which ritual and confessional differences are tolerated”.

Because the sovereignty of Jesus does not extend to the drama of human life, differences between communities need to be tolerated — as a way of managing the conflicts and imperfections that come with being human as much as anything else. To assume Christian doctrine ought to have a monopoly on human behaviour is to suggest Jesus does in fact have jurisdiction in this world. This goes against the injunction: “my Kingdom is not of this world”. The interpretation expressed from Augustine to Pufendorf, by contrast, underpins one of the distinguishing features of modernity: religious and ideological tolerance.

Tolerance also immediately evokes the Enlightenment. And one of the most striking parts of his book is Dusenbury’s comparison between two giants of the French Enlightenment: Voltaire and Rousseau. “Voltaire”, he writes, “is obsessed, in a thoroughly provincial way, with the infamies of Christian Europe”.

The Voltairian position is familiar. Christianity is a bastion of intolerance and persecution. A religion which, left unhindered by the civilising force of secular power, is a threat to universal human rights.

But Dusenbury adds that, “Rousseau, levelling his eye on further horizons, realises that it is Christianity’s critique of cultic violence, and its unease with the archaic temple-state, that must be entered into what Paul Veyne called the ‘inventory of differences’ of global history”.

The temple-state is the synthesis of religion and state. And it is an integral part of the non-Christian world. The key point, as Dusenbury puts it, is that “Pilate is a legate of the Roman temple-state in the Judaean temple-city. For Pilate, as for the Judaean Temple elites who charge Jesus with blasphemy and treason, the codes of religio and the saeculum had not been decoupled. It is in part because Jesus decouples them that he is sent to the cross”.

What are the implications of this? If Jesus died not only to redeem humanity but also to “decouple” the temple from the state, then embedded within Christianity itself is the conviction that religion should have a limited role in organising the civic life of a nation. Expressed another way, the fact that people don’t feel obliged to identify as Christian anymore, and are thus rapidly peeling away from it, is itself a consequence of Christianity.

A large part of why there are so few Christians is because many baby boomers lost interest in Christianity and raised their millennial children without any religious affiliation. The conventional explanation for this is the permissive society from the 1960s onwards, but if permissiveness — my kingdom is not of this world — is deeply woven into Christianity itself then the rapid decline of Christian affiliation is unsurprising. Some now joke, with a mixture of Wildean exuberance and smirk, that the Anglican Church is no longer a Christian institution. But it is simply following a normal path.

Which is not the same as saying it is following a necessary path. There are many strands of Christianity. During the medieval and early modern period many Christian churches did embody intolerance. Today, many Christians (and non-Christians) do intelligently argue that Christianity should play a more prominent part in public life. But religions are complex entities, entangled with deep tensions.

Dusenbury emphasises the oddity of Christianity when he mentions the Justinian law code. The central irony, as he puts it, is this: “Justinian inscribes, at the head of his foyer-text to his monumental code of Roman law (and with it, of much European law), as a sanctifying and legitimating figure, the name of a man who was crucified by a Roman judge as a Roman convict”.

Christianity is, of course, flourishing in sub-Saharan Africa. And the most Christian part of Britain is London — in part due to immigration. But is it any surprise that a religion with the Code of Justinian can also provide the context for its own material demise?

Another counterpoint is that America is officially a secular state while European countries usually have state religions — and the former country has a more vigorous religious culture than the latter countries. This is true. But I am interested in secularisation less as a description of how a country is constituted, and more as a social fact and an evolving process. And even in America the prominence of religion in civic life has been in decline.

Dusenbury’s dense, erudite book is not only a historical account and an exercise in theological exegesis; it is also a veiled commentary on our contemporary religious landscape.

Is this increasingly post-Christian landscape sunny? There was a recent report by a think tank called Onward which found that the proportion of under-35s saying they have just one or no close friends has trebled in the past 10 years: from 7% to 22%. Millennials and members of Generation Z are less likely to be members of a group or participate in group activities than previous generations were at similar ages. And people under 25 are three times more likely than people over 65 to distrust their neighbours.

Joining a Church won’t be a panacea to these issues; but it probably will encourage a wider network of friendships and a greater sense of civic belonging. Then again, as Joseph Henrich pointed out in his book The Weirdest People in the World, the move away from extended family networks to smaller-scale communities is itself a consequence of Christian marriage norms.

Christianity gives with one hand and takes away with another.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe