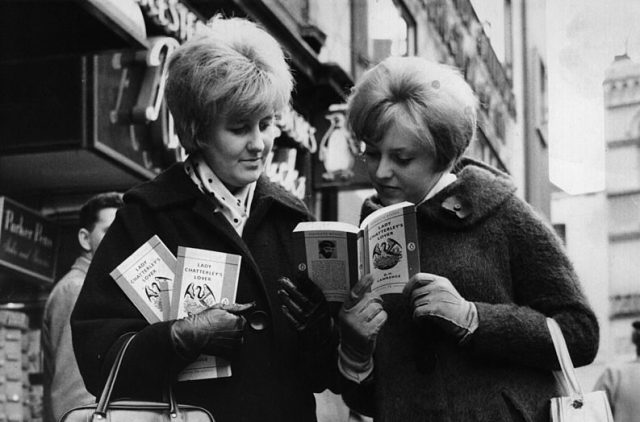

“One must retire out of the herd and then fire bombs into it” said Lawrence. Credit: Keystone/Getty

Had D.H. Lawrence still been alive when Penguin Books were prosecuted at the Old Bailey, in 1960, for their unexpurgated edition of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, he would have been 75 years old. An unlikely age, perhaps, for a mascot of the sexual revolution, but then he was always out of tune with the times. After the Chatterley trial, Lawrence blazed throughout Sixties like a torch and then spontaneously combusted.

The battle between Lawrence and the rest of the world started in 1915 with the censorship of The Rainbow. He called it his “big and beautiful book”, a biblico-mythico epic about the sexual awakening of three generations of women on the borders of Nottingham-Derbyshire. Beginning in 1840, when men were still in wordless communication with nature, it closed in 1905 when railway lines, mineshafts, and a rash of new houses were corrupting the landscape. The novel was sentenced to death before the bench at Bow Street magistrate’s court, where Dr Crippen had recently been charged with murdering his wife; the 1,011 remaining copies were removed from the offices of Methuen, Lawrence’s publisher, and burned by a hangman outside the Royal Exchange.

The Rainbow, the court concluded, was “a mass of obscenity of thought, idea and action” although the prosecutor had difficulty specifying precisely what it was he had found so obscene. Lady Chatterley’s Lover, written 12 years later when Lawrence had nothing left to lose (he died in 1930) contained words like fuck and balls and arse, but The Rainbow was about as offensive as Thomas Hardy.

The real problem with the novel was the author himself, a working-class upstart with a German wife whose own morals were debatable. Frieda Lawrence, it was rumoured, had left her middle-class husband and three children in order to run away with this sex-obsessed miner’s son. Added to which Frieda’s cousin, Baron von Richthofen, AKA the Red Baron, was the only German fighter pilot whose name was known to every Englishman.

After The Rainbow fiasco, Lawrence began a new life as an outlaw. “One must retire out of the herd and then fire bombs into it” he announced, and as soon as the war was over he exiled himself to Europe and then America, firing bombs all the way.

Like Blake, D.H. Lawrence spoke in prophecies, many of which have been proved — not least his anticipation of his own afterlife. This is dramatised for us in a remarkable scene in The Rainbow’s sequel, Women in Love, published 100 years ago this May. Birkin, Lawrence’s alter-ego, is reading quietly in the drawing room when his girlfriend, Hermione Roddice, approaches him from behind with a lapis lazuli paperweight which she brings down with full force on his head. When she sees he is still breathing, she brings it down again but Birkin takes cover beneath his book. It is curious that Hermione Roddice did not become a cult heroine, because women have been bashing Lawrence on the head ever since.

The most lethal blow was delivered by Kate Millett in Sexual Politics (1970), which was effectively the first list of “Shitty Men” in Literature. Millett argued that Lawrence, Henry Miller and Norman Mailer were guilty of misogyny and while Miller and Mailer rode the storm, Lawrence did not. He became, and remains, one of those writers whose name triggers a mental lockdown; in the Seventies and Eighties, for a woman to reveal that she liked D.H. Lawrence was akin to saying that she liked being roughed-up by her boyfriend. Until Burning Man, I kept my own interest in him quiet.

Kate Millett’s bludgeoning of Lawrence was based on her reading of a short story called The Woman Who Rode Away. Written in 1924, when Lawrence was living — or rather dying — in New Mexico, the tale is a dreamlike parable about a bored American housewife who rides off into the desert in order to offer the Chilchui people her heart. Her death, an offering to the Gods, will save the tribe. She is taken by them on a long climb to a cave behind a frozen waterfall where she is laid out for her sacrifice. Lying on the rock slab, she watches for the sun to hit a column of ice, at which point the blade of the knife will be struck into her. It is here that the story ends.

Unlike the prosecutor of The Rainbow, Millett was able to say what she found obscene in The Woman Who Rode Away. It was, she argued, “sadistic pornography”, a snuff movie in “MGM technicolour”. She is right that the story is sick but then, as Lawrence said, “we shed our sicknesses in books”. But should it be read as a story? Lawrence also said that if we read his stories “simply as stories we should not get much satisfaction from them”. This is because he thought in symbols. His own symbol was the phoenix and The Woman Who Rode Away is another allegory of regeneration: modern America sacrifices itself for the cosmic world it has lost. The woman’s death ensures the movements of the planets; the movements of the planets ensure the life of the tribe, and the tribe connects capitalist America to its roots.

The savagery of the tale was its purpose. Lawrence argued in Studies in Classic American Literature, the most dazzling experiment in literary criticism ever written, that the distinguishing feature of American literature was “unconscious duplicity”. In each case a nice-as-pie upper-consciousness disguised a turbulent under-consciousness: “Destroy! destroy! destroy! hums the under-consciousness,” Lawrence wrote, “Love and produce! Love and produce! cackles the upper-consciousness. and the world hears only the Love-and-produce cackle. Refuses to hear the hum of destruction underneath. Until such time as it will have to hear.” In The Woman Who Rode Away his quintessentially American tale, Lawrence makes us hear the destruction underneath. It is Uncle Sam’s ego, and not the woman’s heart, that is being knifed out.

In another of the insights of Studies of Classic American Literature, Lawrence counselled critics “to save the tale from the artist who created it”. And ye gods, does his own writing need saving.

Lawrence had the same concerns as we do today: democracy, free speech, sexuality, the sickness of the modern world, the decay of civilisation, how to be alone. But the voice in which he expressed himself was more startling and original than that of any of his peers. Take the opening sentence of his essay on free verse: “It seems when we hear a skylark singing as if sound were running forward into the future, running so fast and utterly without consideration, straight on into futurity.” Lawrence, too, is breaking into song here. A lifelong claustrophobic, forward movement was his great subject: “Comes over one an absolute necessity to move”, begins his travelogue Sea and Sardinia.

His oeuvre largely confounds genre, but if we have to categorise it we can say that he wrote 10 novels, three of which, Sons and Lovers, The Rainbow and Women in Love, were recognised as game-changers while two — Aaron’s Rod and Kangaroo — are, I suggest, the first examples of autofiction. He also wrote 70 short stories, four of the most innovative travel books of the century, two bonkers studies of the unconscious, thousands of poems, dozens of essays on subjects ranging from syphilis to the novel of the future, a collection of plays set in miners’ cottages that anticipate the work of the Angry Young Men, a history book for school children and, of course, the incomparable Studies in Classic American Literature.

He was less a modernist than the last of the Romantics: Byronic in his audacity, Wordsworthian in his ego, Coleridgean in his mysticism, and Blakean in his insistence that there is no progress without contraries. Contraries were what Lawrence was built upon: remove them, and you take away the structure of his being. His contradictions were numerous: he was an intellectual who valued “mindlessness”, he was a profoundly religious agnostic, he both revered and feared homosexuality. The greatest contradiction of all, however, was his belief in the wisdom of the very body that was failing him. Lawrence had consumption from his youth, and every winter was a near-death experience.

No novelist before him had considered the body as a part of consciousness, but the Lawrentian body bore little relation to the anatomy described by doctors. Lawrence believed, for example, that the solar plexus was the home of the unconscious and source of all wisdom: “I just don’t feel it here”, he said of Darwin, pointing to his stomach area. He similarly believed that we are composed of magnets which lead us hither and thither, and that tuberculosis comes from an excess of maternal love. In other words, Lawrence believed that his mother had literally crushed his lungs. Denouncing science in what his friend Aldous Huxley described as “the most fantastically unreasonable terms”, Lawrence would refuse to be vaccinated today. But at the heart of his eccentricities lay the need to hold onto the mystery and wonder that were fast disappearing from the mechanised world.

So what does the most silenced male writer of the modern age have to tell us? He wrote his own epitaph is in his late poem, ‘Phoenix’:

Are you willing to be sponged out, erased, cancelled,

made nothing?

Are you willing to be made nothing?

dipped into oblivion?

Lawrence suffered all of those things, but he will rise again.

Frances Wilson’s ‘Burning Man: The Ascent of D.H. Lawrence’ is available to pre-order.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe