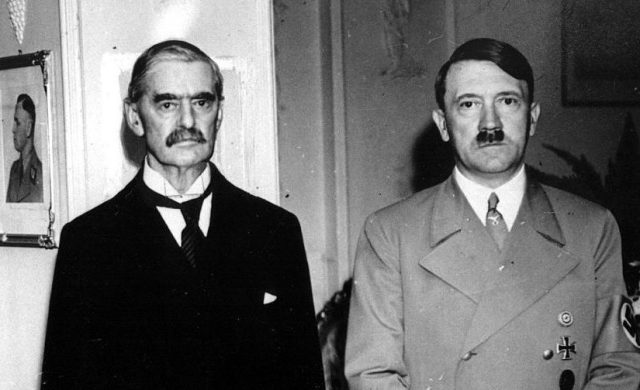

Never the twain: Chamberlain and Hitler. Credit: ullstein bild via Getty Images

On 8 May 1945 – Victory in Europe Day – Harold Nicolson went to a party. Nicolson was a very famous man, one of the first BBC radio personalities, a successful author, an MP and, briefly, a junior minister.

Writing in his diary that night, he asked: “Why did I go to that party?… I went and I loathed it… There… were gathered the Nurembergers and the Munichois celebrating our victory over their friend Herr von Ribbentrop. I left early and in haste, leaving my coat behind me.”

The party had been given by a Conservative MP, Henry “Chips” Channon, who was born in Chicago in 1897 and became ostentatiously and snobbishly more British than the British. Channon, along with many others at the party, had been enthusiastically pro-Nazi and anti-Churchill until deep into 1939 — hence Nicolson’s description of the “Nurembergers” and the “Munichois”.

The VE Day party is interesting for more than its startling hypocrisy. It is one of scores of occasions in which Channon and Nicolson – two of the three great British diarists of the 20th century — wander into one another’s pages.

For many years, I’ve been a great admirer and frequent re-reader of the diaries that Nicolson kept from 1930 to 1962. A writer, broadcaster, diplomat, politician, gardener and closet homosexual, he is, in my opinion, one of the greatest diarists of any century. Henry Channon’s diaries were first published in heavily expurgated form in 1967, and a first volume of the more complete diaries (covering 1918-1938) was published last month, brilliantly and painstakingly edited by Simon Heffer.

The enlarged Channon diaries have rightly attracted a great deal of attention. They do not have the breadth, wit or literary quality of the Nicolson diaries but they are more detailed and more frank, and maybe more honest, about the opinions and sexual escapades of some of the leading figures in British politics and high society in the years between the world wars. And reading the two diaries side by side is illuminating.

The two men were important, secondary figures in the opposing political tribes, the appeasers and anti-appeasers, in the pivotal years from 1935 to 1939. They represented not just ephemeral political viewpoints but opposing philosophies of Britishness which survive, in somewhat different form, to this day.

Both Nicolson and Channon married wealthy, aristocratic women. Both were bisexual and had frequent homosexual affairs while other men, less powerful and less protected, were prosecuted for gross indecency.

They knew each other well, although not as lovers. Both were elected to parliament in 1935 — Channon as a Conservative, Nicolson as a follower of Ramsay McDonald’s National Labour, which supported the Tory-led government.

Nicolson’s diaries introduce you to an extraordinary cast of 1930s and 40s characters, from Winston Churchill to Charlie Chaplin, James Joyce to Virginia Woolf, Charles Lindbergh and Charles de Gaulle. Channon’s are acute, sometimes funny and startlingly frank but frequently tedious, snobbish and self-regarding. You meet Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, before she married the future King George VI. You meet the future Duke and Duchess of Windsor. You meet the leading politicians of the 1930s and hordes of uninteresting aristocrats and junior royals.

The early part of the Channon diaries read like an interminable Daily Mail gossip column, with a new name dropped every sentence and a price-tag for everything. The later part — when Channon becomes a Parliamentary Private Secretary in the Foreign Office — give a compelling, and pro-Nazi, insider’s view of one of the most controversial periods in British politics, leading to the Munich crisis of 1938.

As political thinkers, there is no comparison between the two men. Nicolson (although close to Sir Oswald Mosley before he became a full-on fascist) understood clearly what was happening in Berlin and wrote and spoke and conspired against it. Channon’s diaries, in contrast, leave him very much marooned on the wrong side of history. Adolf Hitler, he writes in September 1938, is “always right, the greatest diplomat of modern times”. Winston Churchill, he writes in May that year, is a “fat, brilliant, unbalanced, illogical, porcine orator… All his life he has preached against (the Germans) and thus done much to poison our relations with Germany.”

The extent of Nazi fellow-travelling among a part of the British upper and governing classes in the 1930s has been well-documented but is seldom mentioned these days. A new biography of the novelist Barbara Pym reveals that she — the archetype of a certain kind of British decency and good sense — was also an enthusiast for the Nazis and had an affair with an SS officer.

The excuse usually given — and a reasonable one up to a point — is that we have the leisure of reading history from back to front. We know how the story ended. For many upper-class Britons in the 1930s, the Soviet Union appeared a greater threat than the Nazis, who might be a bulwark against Communism and its threatened destruction of wealth and tradition.

But Channon goes even further, praising the “virile” ideology of Mussolini, Franco and Hitler compared to a “tired” and “declining” Britain. “Germany and Italy are seething with vigour and life,” he writes: “Democracy is absurd.”

On 20 September 1936, Channon and Harold Nicolson were at the same house — or more strictly “castle” — party at Schloss St Martin in Austria. Their respective diary entries for that day are telling.

Channon and his wife Honor Guinness, daughter of the Guinness family grand patriarch, Lord Iveagh, had been to the Olympic Games in Berlin. They had been invited as personal guests of Joachim von Ribbentrop, former champagne salesman and Hitler’s ambassador in Britain from 1936 to 1938, and later the German foreign minister.

Nicolson wrote in his diary that night: “The Channons have fallen under the champagne-like influence of Ribbentrop… They think… that we should let gallant little Germany glut her fill of the reds in the East and keep decadent France quiet while she does so.”

“I say that this may be expedient but it is wrong… We stand for tolerance, truth, liberty and good humour… [The Nazis] stand for violence, oppression, untruthfulness and bitterness.”

Channon’s diary entry that day is both generous and patronising. “Harold Nicolson arrived, dear sentimental, hard-working, gentle Harold, who is always a victim of his loyalties. He refused to go through Germany because of Nazi rule… I am worn out with Nazi discussions.”

While in London, Von Ribbentrop (and through him Adolf Hitler) was originally courted by a wide section of British high society and the Conservative Party. But he made himself a laughing stock with a series of gaffes, including giving the Hitler salute to King George VI, earning the nickname “brickendrop”.

Channon was among the few who defended him to the end (while also mocking him). He describes Von Ribbentrop’s eighteen months in London as a “missed opportunity” for an Anglo-German alliance (implicitly against France). In 1946, Joachim Von Ribbentrop was convicted of crimes against humanity at the Nuremberg trials, and became the first Nazi leader to be hanged.

In the period from 1936 to the Munich crisis in 1938, Nicolson was a frequent parliamentary speaker and a member of a group of dissident, strongly anti-Nazi MPs surrounding Anthony Eden. Meanwhile Channon became parliamentary private secretary to the junior foreign office minister Rab Butler (a keen appeaser).

The two diarists evidently fell out. Channon says of Nicolson in March 1938 that he is “a bit mad, but all old women have a change of life.” He uses the word “wet” or “wets” or “moist” to describe Nicolson and all supposedly pro-government MP’s who were anti-Hitler.

The situation deteriorated and on 28 September a war over Czechoslovakia appeared imminent. Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain (“the greatest ever Englishman” to Channon; a man with “no conception of world politics” to Nicolson) addressed the House of Commons. In mid-speech, however, a message arrived from Hitler inviting Chamberlain to further peace talks in Munich. Tory MPs stood on their seats and waved their order papers.

Both men recorded the event in their diaries. Channon wrote: “There was born in many, in me at least, a gratitude, an admiration, for the PM, which will be eternal. I felt sick with enthusiasm, longed to clutch him.”

“I remained seated,” Nicolson recorded: “Liddall (the Conservative Member for Lincoln) behind me, hisses out: ‘Stand up. You brute.’”

Of the “peace for our time” surrender to Nazi demands two days later, Channon wrote: “The whole world rejoices while a few malcontents jeer… Chamberlain gave in on a few minor points but he saved the world which does not want to go to war over a timetable.”

In his diary, Nicolson described the Chamberlain government’s position: “This is the greatest diplomatic achievement in our history: therefore we must redouble our armaments in order never again to be exposed to such a humiliation.”

Two further volumes of Channon’s diaries are to be published. He appears seldom in the two later volumes of the Nicolson diaries but the two men seemed to have become friends again — of a kind — hence the brief visit to the VE Day party. But Nicolson does mock the grandiosity of Channon’s post-war lifestyle. When he receives pocket handkerchiefs for his birthday one year he writes: “(They) will be preserved for those occasions when I dine with Emperors and Princes or Queen Mothers or Mr Henry Channon.”

For all his political views, Channon comes across as a self-absorbed, shallow but in many ways likeable man. He was a contradictory figure, American-born but detesting the United States (while living partly off American money). Living in an aristocratic world which no longer exists, he thought the rise of American power was a threat to the royalist-aristocratic-high Christian-traditional values that he professed to cherish (while living a somewhat untraditional private life of brothels and bisexual affairs).

All the same, his voice is recognisable 80 years on. He represents a kind of inward-looking glorification of Britishness which can still be heard today. Paradoxically his successors often dwell simplistically on Britain’s part in the defeat of the Nazis whom Channon so admired.

Nicolson – the idealistic “wet” — had simplifications and contradictions of his own. He was a devotee of the League of Nations and international cooperation; he believed in Britain’s vocation as a model for decency, law, freedom and truth-telling. And yet, by contemporary terms, he is certainly racist and at least mildly anti-Semitic.

Eight decades on, the two have almost switched positions in popular memory. To be anti-Hitler is to be “wet” no longer. Nicolson, the “sentimental old woman”, represents with Churchill and Eden the far-sighted defence of Britain’s freedom and values against violent, bullying dictators. Channon, in contrast, the supposed champion of “virility”, now embodies a failed policy of short-sighted vacillation and appeasement.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe