Mess with Big Social at your peril. Credit: Netflix.

Let’s call her Laura. In September, Laura was out in Leeds City Centre, buying some bits, when her card was declined. Funny, she thought. She definitely wasn’t in the red. But these things happen, so she left the shop, tinting crimson, and dashed towards the nearest cashpoint.

But her card wouldn’t work at the cashpoint either. She tried another one. With the same result.

Laura opened the banking app on her phone. It said only ‘error’, then automatically closed.

She finally abandoned her shopping and went into the nearest branch of Santander. There, the counter assistant seemed just as mystified. After about an hour of waiting, though, Laura was called through into the manager’s office.

“I’m going to read a statement out for you,” the manager said. “But I’m not going to be able to answer any of your questions after that.”

He read out:

“We have locked your bank account. We can’t give you any more information. We might be in touch in future with more information. But we don’t know when that might be.”

Could she have her money? No.

But how was she supposed to get home? After all, she lived eight miles outside of Leeds, and now she had no bus fare. Apparently, this was not the bank’s business.

This low-rent version of The Trial went on for another three weeks. Frequently, Laura would phone up Santander customer services. She’d be put on hold for ages. Then the phone would just go dead. She wrote to Santander to complain. They wrote back: they weren’t interested in her complaint and wouldn’t be taking it any further. Meanwhile, her rent, standing orders and Direct Debits stacked up, the late fees and penalties mushroomed around them, as life tumbled towards chaos.

Nearly a month on, she received a letter from Santander:

Under the terms and conditions… we can withdraw banking facilities at any time, and in line with company policy we don’t give further details.

The account had been closed. Without apparent irony, the balance had been appended as a cheque.

‘Laura’ could be any of us. But she is also Laura Towler, one of the founders of Patriotic Alternative. Towler is a sort of next-gen BNP type, a net-savvy white identitarian who campaigns against mass-migration, and occasionally winks to her Telegram followers about ‘you know who’ (they know alright: The Jews). It would seem that Towler had been expelled from Santander for her views. But in line with the bank’s conditions, this has not been made clear.

By a strange coincidence, in the same month, the same thing happened to Mark Collett, her Patriotic Alternative co-founder. Only, Collett doesn’t bank with Santander — he is with HSBC. Somehow, the same thing also happened, in different countries, to Europe’s leading young white identitarians: Brittany Pettibone and Martin Sellner.

Coincidence abounds in the modern world. Last year, on the other side of the Atlantic, various alt-ish-Right figures who banked with JP Morgan Chase woke up on the same morning to find that they no longer banked with JP Morgan Chase. They included the chair of the Proud Boys Enrique Tarrio, former InfoWars staffer Joe Biggs, Project Veritas associate Laura Loomer, and Martina Markota, a Trump-supporting performance artist.

Of those four, it’s the other Laura whose case drives home the full capriciousness of corporate power in a networked age. Loomer styles herself as the “most banned woman in the world”. In addition to Chase, she is banned from PayPal, from VenMo, from The Cash App, Airbnb and Instagram, from Lyft, Uber and UberEats, from the blogging monetisation platform WordAds and the t-shirt print-to-order site TeeSpring, from Twitter and Facebook — obviously — and from any one of a half dozen other platforms for digital congress.

Some of these bans are strongly self-inflicted; controversy is her currency. She got booted from Uber in 2017 after ranting about being unable to find a taxi driver who wasn’t Muslim in Manhattan, in the hours after the NYC terror truck attack. Twitter banned her in 2018, after she laid into Ilhan Omar, the Muslim Congresswoman, claiming, scandalously, that Omar was part of a religion in which “homosexuals are oppressed”, and ”women are abused” and “forced to wear the hijab.” Later that month, wearing a gold ‘Juden’ star (Loomer is Jewish) she handcuffed herself to Twitter HQ, to protest the decision.

But many of those bans are mere cascade effects. TeeSpring works with PayPal. PayPal had already declared Loomer an unperson, and thus they informed TeeSpring that they would have to stop supplying her. Ditto Venmo and The Cash App.

You don’t want to mess with the people who make the widgets that undergird the financial system. In 2018, in response to activist pressure, MasterCard began choking off various far-Right and internet Right figures. That in turn meant their often lucrative Patreon accounts were cancelled: YouTube ‘Classical Liberal’ Carl Benjamin lost $12000 a month. Now, in a post-Covid world, where we’re often being told that cash is no longer acceptable, some are also being told that electronic banking is no longer for them. It’s an interesting crossroads.

The likes of Towler might be distasteful. But if that alone is the bar for the arbitrary exercise of power by, say, the PR department of NatWest, then all kinds of people — from Cat Bin Lady down — stand to be unpersoned.

Right of admission is always reserved — we all know this — and you might say that these examples are just the market at work. Except that some things are so fundamental to our everyday lives that they’re not so much markets as the thing that you need in order to use a market.

In the dying days of Gordon Brown, an attempt was made to guarantee every citizen’s right to a current account. It was quickly shot down by the Big Five banks (after all, it wasn’t as if they owed the government any favours). A decade on, that tide is further out than it has ever been.

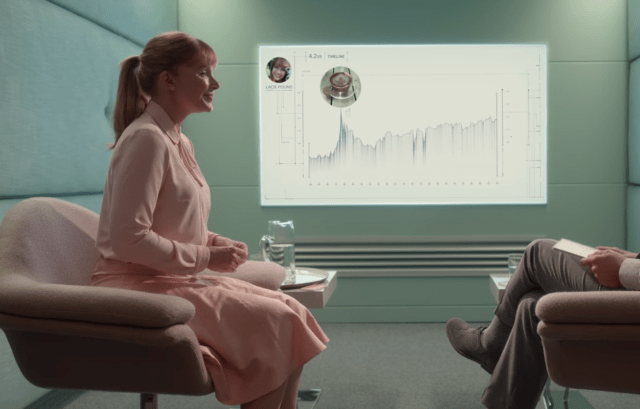

In the banking system’s capacity to disable the individual without pro-actively doing them harm, there’s an echo of the elegance of the Chinese government’s social credit. “There was no file, no police warrant, no official advance notification. They just cut me off from the things I was once entitled to. What’s really scary is there’s nothing you can do about it,” was how Liu Hu put it — a Chinese journalist, who ran afoul of social credit in 2019. But perhaps Black Mirror’s ‘Nosedive’ episode would be a more apt comparison. In our hemisphere, that kind of deletion is done more cheerily, coated in the veneer of freedom of choice and association, by PR and HR, not by the grey monolith of The Party’s star council.

Increasingly, we allow our corporations to police the soft boundaries of acceptable speech and thought, from Sainsbury’s rejection of ‘racist’ shoppers to the Yorkshire Tea wars to Tampax’s latest bloodbath.

Ironically enough, the license that companies now take as part of their remit is a perfect mirror image of the Cake Problem: the oft-rehashed libertarian thought experiment, over whether a fundamentalist Christian cake-maker should be forced to bake a cake for a gay wedding. When US Libertarian Party candidate Gary Johnson was posed the question in 2016, he said that they should — and added that he would equally require a Jewish baker to make a Nazi wedding cake. The underlying principle is one of neutrality. Where two belief systems clash, if they remain polite and cooperative, shouldn’t the public still retain an underlying right of service?

Evidently not.

Another great thought experiment dawned in August of last year, when Laura Loomer stunned the Republican establishment by winning the GOP primary for Florida’s 21st Congressional District. The 21st is West Palm Beach, where Mar-a-Lago lives. Trump himself has already cast his vote for her.

Clearly, Loomer’s campaign has been adversely affected by her various bans. At the time of her deletion, Loomer’s tweets were getting 150 million impressions a month. As she puts it: “They just assume that people can afford TV, and that they’re not going to get all their information through social media.” She might have wingnut tendencies, but Loomer is also half of the choice for voters in the 21st District.

This year, “in the interests of transparency and fairness”, Twitter has given every single candidate standing in the US election a blue-check verified account. So, when she won her primary, she applied to have her accounts reinstated.

No dice. She can’t get on Big Social, the broadcast networks are ignoring her, and her opponent, Lois Frankel, won’t even say her name, let alone debate her.

Should she win — still a long shot — Loomer has sworn to spend her time on Capitol Hill breaking up the tech giants’ monopoly. So couldn’t it be said that they’re acting to titrate their own legislative environment?

F.A. Hayek, and his prophet on earth Margaret Thatcher, saw the market as the best bulwark against tyrannical state power — that by pulling lots of little levers every day with our cash, we’d effectively be voting, in a constant dialogue of mini-democracy. It was only towards the end of their regime that the Thatcherites began to realise that some things — from trains down — remain public utilities in spirit, no matter who runs them.

As the Hunter Biden story still freezes the New York Post’s Twitter feed, it seems the power of the corporate lever-pullers to mould the outer edges of democracy is as strong as it has ever been. We can vote with our wallets, sure. But what if the scope extends way beyond a single product line, into an entire kind of product, or the social architecture that makes products possible? What if the lever-pullers are our wallets?

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe