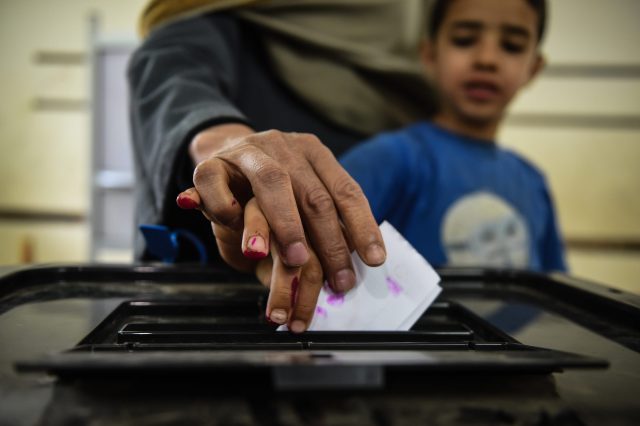

Credit: MOHAMED EL-SHAHED/AFP via Getty Images

The coming election could shape Britain’s future for generations to come. And yet 11 million of our fellow citizens will be denied a vote on December 12th — and no one seems to care. Children are barred from participating in our democracy by a system of ageist prejudice; nothing magical happens when you turn 18 — or 16 for that matter. All citizens should have a voice. All children should have a vote.

“Will you let them drink and smoke, too?”

This is usually the first response I get when I propose enfranchising all citizens under the age of 18. The answer is, obviously, no. We have laws that prevent young people from drinking and smoking because these things are harmful. Voting, by contrast, is not harmful; drawing an X on a ballot paper is substantially less dangerous than inhaling toxic smoke into your lungs.

Before you start freaking out, let’s be clear: this wouldn’t mean the sudden election of a government that promised free ponies and paintball instead of the NHS. At the last count, 17% of the population were under the age of 18, and I am not proposing that only children should vote — simply that they deserve to have a voice in shaping our shared future.

Still, there are two significant arguments for continuing to deny children the vote. Firstly, that they are too young to understand politics, or the consequences of their decisions; secondly, that they are vulnerable to outside influence, and will just vote the way their parents do — or against their parents to spite them.

The first is a reasonable concern. But we have already set, as a nation, an age threshold at which we expect children to understand the law sufficiently to be able to abide by it. It’s the age of 10: the age of criminal responsibility in England. From 10, a child is required to follow the law, and if they do not, they can be punished by the state.

How can we argue that a 10-year-old has the judgement required to understand the law and the consequences of breaking it — and then argue that a 10-year-old doesn’t have the judgement required to understand democracy or the consequences of voting? If you have to follow the law, you should have a role in making it.

And until you reach that age of 10, your parents should be able to cast your vote as your proxy. Clearly, a small baby would struggle to exercise their vote directly, given their basic inability to control a pencil. But a parent with a second vote, to cast in their child’s name, could be expected to consider that child’s interests, and talk to them about their choices and ideas from an early age.

Of course, this brings us to the argument of undue influence. Whether the parent is directly casting their child’s vote or not, we can expect the family environment to shape a child’s choices. But then, you could say the same thing about any one of us. None of our votes really make sense, from first principles. We all have stories and experiences that shape our political identities — and the votes we cast from election to election. If some children vote the way their parents do, that makes them no different from millions of adults. If some children vote to spite their parents, the same is true of some adults.

If some children vote without really understanding the facts; if some spoil their ballot paper with a drawing of a penis; if some vote for the candidate whose surname starts with A simply because they’re at the top of the list; if some vote for the party with the prettiest logo: they are simply following in the footsteps of generations of voters before them.

There is no test of wisdom or thoughtfulness for over-18s. A distant relation of mine voted Leave in the referendum convinced that Turkey had already joined the EU. She was wrong. But she still had the right to vote: the right to be wrong, and the right to be heard anyway. We shouldn’t use age as a proxy for seriousness: we should enfranchise every citizen, wise or foolish, young or old. The right to vote should be inalienable.

Now, there is a toxic movement, in particular on the Remain side of the Brexit debate, to celebrate the idea that Leave voters — and social conservatives more broadly — are dying off. That’s evolved in some places to proposals to strip the vote of the over-70s, arguing that they don’t have a stake in the future, in the way young people do. These arguments are repugnant. Every citizen has a right to their vote, no matter their age.

But we do have a problem when the electoral system is inherently biased towards the 83% of the population who are over 18. By granting the vote to all children — exercised by proxy until they reach 10 — we would simply rebalance the system to recognise that all citizens are equal.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe