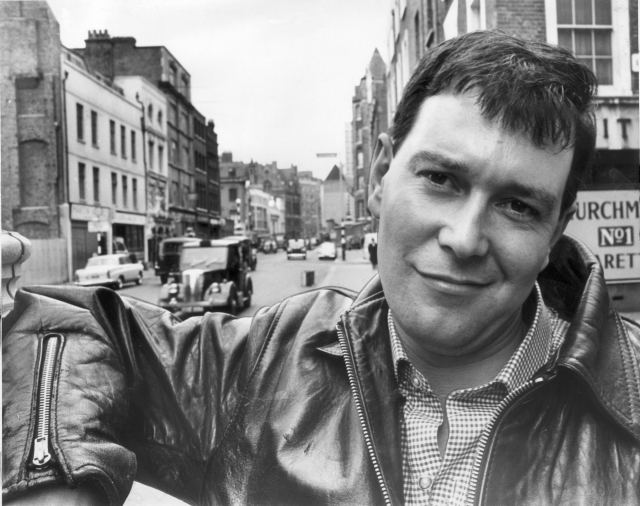

Joe Orton. Credit: Mirrorpix/Getty

They’re sticking it up. A gigantic erection in the city centre. A great whopper displayed to the public.

To make a filthy joke is the most obvious first reaction to hearing the news of the campaign to mount a statue of the playwright Joe Orton in his hometown of Leicester. The extremely rude and extremely funny playwright would surely do the same.

But then what? Would he really want such an accolade? You can understand the public interest: Orton’s sudden rise to theatrical fame in 1964 with the plays Entertaining Mr Sloane and Loot, and his sudden death at the hands of his lover, Kenneth Halliwell, just three years later, will continue to fascinate for as long as celebrity, bad taste and death continue to fascinate human beings. His diaries are a candid chronicle of that outrageous life. In fact, his true-life story and its grisly denouement have rather blotted out the plays themselves. (There are only three full-length ones – Sloane was followed by Loot in 1966 and the third, What the Butler Saw, was produced posthumously.)

More famous, arguably, is the 1987 biopic, Prick Up Your Ears, by Alan Bennett and Stephen Frears starring Gary Oldman, which cemented the public image of Orton into the cultural consciousness – a prodigiously promiscuous homosexual and brilliant writer of black comedies who came to a sad end because of jealousy both sexual and professional. So perhaps, then, since the mores of British society have shifted so much since 1967 – Orton was murdered mere days after male homosexuality was made legal – it’s appropriate he should receive this statuary immorality, as much a reminder of that precocious talent as of righted wrongs.

But I’m still not entirely convinced. I think Orton’s work, which sadly exists under the shadow of his life and death, is as much in opposition to the values of today as it was to the values of the 1960s. And we are in danger of smoothing away the jagged edges of his genius. There are broken bottles in there.

There is something admirable in campaigning for the civic commemoration of a person whose entire schtick is a condemnation of civic society, who was sent to prison for the systematic defacing of library books, and whose final play ends with the penis from an exploded statue of Churchill being held aloft. Viewed in this light it could almost be seen as what is now known as an “epic troll”. Orton the work – if not Orton the man – is all about mocking the sacred, knocking down the statues.

It’s hard to think of an institution or value that Orton doesn’t punch at in his plays. The work ethic, the war, religion in general and Roman Catholicism in particular, the police. The plays are all about the humour to be found in people hiding venal and carnal motives behind respectability – the observant Catholic nurse repeatedly marrying old men for their money following the convenient deaths of their wives, the respectable middle-aged brother and sister who are prepared to overlook the brutal murder of their father in favour of a sexual time-share of his murderer, the policeman who uses the excuse of shining British justice to rough up young men for his own gratification.

There is a still-astonishing lack of compassion and empathy in his work – in fact, that lack may be even more deeply felt by modern audiences. There is explicitly no advocacy for social change. Orton is an uproarious laugh at people and things as they are, with no plan – no hope – for what they should be. All attempts to improve humanity, from prayer to psychoanalysis, are portrayed as humbuggish fronts for people getting what they can for themselves.

In some of these areas he was not unique for his time; his work fits in with the swell of questioning authority that took place in the Sixties in the theatre and beyond. What makes Orton different from his peers, though, is that he also took shots at things that we still hold to be sacrosanct today, some perhaps even more than in his time: consent, the age of consent, sensitivities about race.

In What the Butler Saw alone, various female characters use the threat of false rape accusations; a barely legal hotel bellboy is enjoyed by the entire company and, offstage, is said to have pleasured a class of schoolgirls; “white golliwogs” are invoked to calm “colour prejudice hotspots”. This is a man who wrote in his diaries about sexual fantasies involving “mentally defective farm labourers”, and that’s one of the more palatable sexual digressions in its pages.

Perhaps the funniest clash between then and now is the claim made by some prominenti of the campaign that Orton was an ‘LGBT+ pioneer’, a ‘trailblazer’, who in that most ghastly word of our times, needs to be ‘celebrated’. Yet he is not a saintly Alan Turing, even less a cuddly cheeky Graham Norton.

It’s tempting to imagine what Orton would make of the modern LGBT movement if he were alive today. It has all the markings of an Orton target – blatant cant, automatically assumed virtue, and recourse to confected outrage when questioned. At the recent Pride event in London, there was a supportive flypast by the Red Arrows, which is possibly the most insanely, gloriously Ortonesque thing that has ever happened in the real world.

The statue campaign also states that Orton was “the first person to put gay characters on stage”, but even this claim is a bit rum. The randy young men of the plays are all gleefully, mercenarily bisexual. The only exclusively homosexual character in Orton is Ed, the marvellously repressed “uncle” to Mr Sloane, who obsesses about young lads in tight shorts “keeping themselves clean” by doing plenty of strenuous physical exercise and avoiding getting into “trouble” with girls. His sexuality and its repression is something we are encouraged to laugh at. He is certainly not what we would consider a Stonewall role model or good ‘representation’.

This attempt to sanitise and defang Orton is saddening. If he were working today, his latest play would be about randy teenage boys robbing graves while disguised as transwomen in burqas. If there is to be a statue of the great man – and he was great – let it reflect his true, sometimes truly horrible, genius. He should be portrayed with a white golliwog in one hand and a prodigiously endowed 18-year-old in the other, to remind us of how we always need to be upset, and of how funny that can be.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe