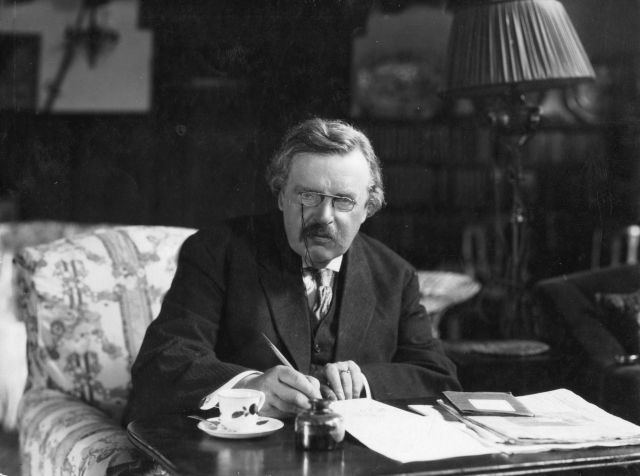

Gilbert Keith Chesterton doesn’t deserve to be canonised. Credit: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Back in the mid-1980s, when I was researching my biography of Gilbert Keith Chesterton, I interviewed an elderly man who as a youth had met the Roman Catholic author and journalist. They were both on their way to Westminster Cathedral, and as they turned onto Artillery Row, the young admirer blurted out to his hero, “Artillery Row. Perhaps they’ll canonize you.” Chesterton, apparently, was not at all amused.

That lack of amusement has extended to the man’s many admirers over the past weeks, as the Roman Catholic Church rejected the author for the canonisation process partly due to his alleged anti-Semitism. Bishop Peter Doyle, of Northampton, added that there was a lack of a “local cult” and “pattern of personal spirituality”, around the man, but it’s certainly been his writings on the Jews that have caused the greatest resistance.

Cult or otherwise, there are Chesterton societies and magazines all over the world, and since the 1970s in particular he has been regarded as one of the great Catholic apologists – a man who managed to communicate often tangled theological beliefs with clean and clear popular appeal. American conservative Catholic thinkers are especially dedicated to this English-language writer, seen as one of their own, and their influence in the Vatican under Pope John Paul II helped to further the cause.

It must all seem somewhat esoteric, even obscure, to most observers. Chesterton was who he was and will remain so, hagiographical acknowledgement or otherwise. Yet saint-making still matters, whatever the cynics may say, and to have accepted Chesterton as a saint would have been profoundly controversial. This would have been the Roman Catholic Church placing its highest seal of approval on a man who many believe disliked Jews, at a time when even the most optimistic commentator would agree that the ghoul of anti-Semitism has found new life.

Controversy wouldn’t be new, of course; the entire business of saint-making has always been touchy and messy. The process isn’t supposed to begin until a hiatus of five years after someone’s death and then there has to be evidence of “heroic virtues”, proven miracles, and so on.

The Roman Catholic Church’s official teaching is that it doesn’t make saints, it merely recognises them, but that’s a little disingenuous. Holy lobbying has become a big business, and one drenched in church politics, which is why different groups back conservative and progressive figures for the process. Whatever the Church may claim, there is a pronounced political and ideological division both in clerical and lay circles.

For example, those who worked to promote the cause of Josemaría Escrivá, founder of the traditionalist Catholic group Opus Dei, came from the opposite side of church politics to those behind the campaign for Óscar Romero, the bishop in El Salvador murdered by a fascist gang for his support of the poor and opposition to the government. But both groups have to be accommodated in a game of ecclesiastical balance.

It’s also why Mother Teresa and Pope John Paul II were rushed to the front of the queue – with insufficient consideration of the former’s links to repugnant despots, and the latter’s – whatever his undoubted strengths – alarmingly flaccid response to sexual abuse within the clergy.

Then there are the legions of saints with dubious records, such as local hero Thomas More. He was a martyr for the cause, he was brilliant, but he also personally ordered and supervised the gruesome torture of those who questioned Catholic beliefs. That somewhat inconsistent element to his moral character was conveniently ignored, partly because when he was canonized in 1935, the Papacy was eager to emphasize its status and honour those who agreed with it, and because England was in dire need of some new compatriots confirmed to be in heaven.

Chesterton is equally problematic, if less tangibly so, and the reason why his treatment has upset many of his devotees is not, for the most part, because they defend anti-Semitism, but because they deny the author of the Father Brown stories, The Man Who Was Thursday, The Napoleon of Notting Hill and volumes of compelling journalism was an anti-Semite in the first place.

Indeed his popularity among Catholic thinkers, and secular conservatives, has grown rather than diminished since his death in 1936, due to his undoubted wit as a writer, and his genuine cleverness and ability to charge through clutter and hypocrisy, like some grand knight of paradox and traditional values. His observations still seem highly relevant: “The Christian ideal has not been tried and found wanting. It has been found difficult; and left untried” he wrote in ‘The Unfinished Temple’, in (What’s Wrong with the World, Collected Works, 1910) “A dead thing can go with the stream, but only a living thing can go against it” (The Everlasting Man, 1925) and “My attitude toward progress has passed from antagonism to boredom. I have long ceased to argue with people who prefer Thursday to Wednesday because it is Thursday.” (New York Magazine, 1923)

Chesterton’s gift, his charisma if you like, was the ability to be a middleman of intellectual ideas and popular curiosity. He could explain philosophy to the masses, and mass to the educated atheist, could write weekly and sometimes daily newspaper columns that roared with cleverness, and then produce a biography of St. Francis or Charles Dickens that impressed life-long devotees. When he published his life of Thomas Aquinas, the world-renowned Thomist scholar Étienne Gilson was distraught. “For many years I have studied St. Thomas and written on him and now a journalist writes a better book about him than I have!”

Yet within Chesterton, within the style and the brilliance and the originality, there was something darker. Richard Ingrams, an admirer, put it well when he wrote that he, “shut his eyes to a great deal of the unpleasantness and cruelty in the world, including his own circle.” He was likely referring to his brother Cecil, and to the author and polemicist Hilaire Belloc, who undoubtedly had a major influence on the much gentler and kinder Gilbert Keith.

Cecil Chesterton was a journalist and editor of limited talent, but was revered by his younger sibling. Cecil was obsessed with what he saw as the negative Jewish influence in media and finance; led a vitriolic campaign against the handful of Jewish figures who were involved in the 1912 Marconi Scandal – an early form of insider trading, mostly involving non-Jews – and, with the far more talented Belloc, developed a virtual ideology based on the belief that Jews were alien to British society and a direct threat to its future.

Cecil died at the end of the First World War, through illness rather than combat, and shortly afterwards Chesterton wrote an open letter to the Lord Reading (Rufus Isaacs, the first Jewish Lord Chief Justice of England), as the politician was about to travel to Versailles as part of the British delegation to the peace conference. It’s drenched in anti-Semitism, with references to “the Jewish international”, “alien psychology”, and “Daniel, son of Isaac, Go in peace, but go.”

But there is much more than letters written in grief, perhaps under the influence of friends. Chesterton may have been led further along a dark path by those around him, but his mingling of misplaced medievalism, English insularity, and instinctive distrust of what he always offensively assumed to be Jewish characteristics, led to his own brand of error and cruelty. Many, though far from all, of his contemporaries may have had prejudices about Jews, and sometimes expressed them, but it was Chesterton’s frequent comments, his attacks and then defence of his position or attempted justification, that singles him out.

In his book A Short History of England, for example, Chesterton praised the expulsion of the Jews by Edward I as the actions of a “tender father of his people”; in his journalism he condemned the British press for opposing the French military and establishment’s anti-Semitism during the Dreyfus affair; and even called for Jews to be forced to wear a form of public identification.

Then there were the clawing vulgarities. In On Lying in Bed and Other Essays: “I am fond of Jews/Jews are fond of money/Never mind of whose. I am fond of Jews/Oh, but when they lose/Damn in all, it’s funny.” And this from The Flying Inn: “Oh I knew a Doctor Gluck/And his nose it had a hook/And his attitudes were anything but Aryan/ So I gave him all the pork that I had, upon a fork/Because I am myself a Vegetarian.”

His defenders argue that he was a Zionist, but that’s far too facile an analysis. While many at the time who supported the creation of a Jewish state did so because they thought it would lead to Jewish security and dignity, Chesterton was more concerned with what he was convinced was the foreign, un-English nature of the Jewish people. In other words: find them somewhere else to live. This was a natural – an inevitable – consequence of his obsession with what he referred to as “the Jewish question”, and incessant references to “plutocrats” and “financiers” – a vocabulary that would soon become part of the litany of genocide.

The other common defence is that he – and Hilaire Belloc for that matter – were vehemently anti-Nazi. That’s certainly true, though they also cheered for fascism elsewhere, especially when it was wrapped in Catholic nationalism. Chesterton wrote of thousands of Jews being “rabbled or ruined or driven from their homes” by the Nazis, who “beat and bully poor Jews in concentration camps”, and how, “I do indeed despise the Hitlerites.”

He died before the Holocaust was fully implemented, and with his authentic opposition to eugenics and his hatred of what he saw as “Prussian barbarity”, he would likely have been disgusted. But opposition to mass murder and ethnic cleansing doesn’t forgive someone of anti-Semitism, and those who help to create a climate where racist atrocity is permissible share a certain responsibility for its reality.

While the claim might groan in its banality, he certainly did have Jewish friends who he sincerely liked, he was appalled by the idea of Jews being harmed because of who they were, but he also played a game of grimy hide-and-seek around the issue, popping up to provoke and condemn, and then claiming innocence or, as his partisans would claim today, purity of intent. That just won’t do.

I once thought, perhaps with far more sanguinity than was deserved, that when weighed in the balance, GK Chesterton may not have been completely on the wrong side of history – that at least he wasn’t part of the problem, and that when the testing-time came he saw the threat before others were aware. No longer. He may not have been the worst, he may well have changed his mind if he had lived longer, but the damage was done.

As Jew-hatred gains a shockingly new prominence, its proponents look to anybody who offers an intellectual underpinning to their venom. Chesterton, tragically, is one of theirs. No saint he.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe