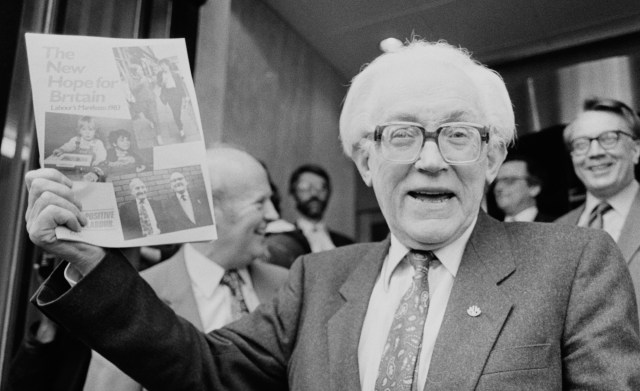

Michael Foot brandishes Labour’s manifesto at a meeting ahead of the general election in May 1983 (Photo by Hilaria McCarthy/Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

June and July were supposed to be quiet months for the Labour Party: the Conservatives would be busy electing a party leader, so it could sit back and let Brexit grind on, hoping no one would pay it undue attention until the party conference in September. The lessons of last summer, when the political agenda was swamped by the repeated accusations of Jeremy Corbyn’s anti-Semitism, were supposed to have been learned. This summer would be characterised by restraint and calm.

It was never to be. There have been repeated lurches into the political mire, characterised best by Len McCluskey on the Andrew Marr Show defending the Labour leadership’s then position on Brexit by morphing into Corporal Jones. His desperate pleas of “Don’t Panic” to Labour MPs sounded a lot like a Dad’s Army rerun on BBC2. He conjured the unfortunate image of Jeremy Corbyn as Captain Mainwaring, John McDonnell as Sergeant Wilson and Tom Watson as private Frazer – muttering “we’re doomed, doomed”.

This wasn’t the only recent echo from the 1970s. Corbyn, apparently, is reading up on Harold Wilson for inspiration over Brexit.Which is remarkable because Wilson was the subject of constant attack from the Left during his time as Labour Party leader and prime minister. He was party leader for 13 years (1963-76), fought five general elections (defeating the Conservatives in four) and held the party together in a time of huge and competing political egos on both the Left and the Right.

For the centre-Right of the Party, Europe was the issue – crystallised by Roy Jenkins leading 69 Labour MPs to vote for entry into the EEC against the Party whip in 1971 and the creation of the breakaway Social Democratic Party ten years later. For the Left, led by Tony Benn, it was the fight for a radical economic agenda and departure from Europe.

Wilson was accused by both sides of lacking ideology and being merely a “master tactician”. He held both wings together by leadership skills that are not recognised in today’s Labour Party: compromise, non-ideological responses to problems (often characterised as mere opportunism), and the ability to read the electorate and exploit the weakness of Labour’s opponents.

It’s hard to see Corbyn acting in the same ways. In the past two years his leadership has been dominated by rigidity over both Brexit and antisemitism that has turned both into full blown crises. It is the opposite of the way Wilson addressed the issues of his day. It is also reflective of the lessons learned by the Left that have been carried from 1979 into today’s politics of the Labour Party.

The generation of young activists of the 1970s and 1980s – Corbyn, McDonnell, McCluskey and Jon Lansman – all earned their political stripes fighting the Right of the party. Lansman had been in the Campaign for Labour Party Democracy and the campaign to elect Tony Benn deputy leader in 1981; Corbyn had been a trade union official in London during the winter of discontent in 1978-9. McDonnell had been deputy leader and Finance Chair of the Great London Council from 1981. McCluskey had been in Liverpool associated with the Militant Tendency that ran the Labour Party and council in the early 1980s.

From 1978-1982 the young activists were dominant within the Labour Party. They depended on influencing supporters in constituencies, trade union branches and the National Executive to fight the power of the Parliamentary party. It was not to last. Mere Influence was not enough. In 1983 Labour under Michael Foot went down to its worst election result since 1918. It’s still the worst result in modern times and caused by the combination of the turmoil within the party, the split away from Labour by the Social Democratic Party and the Falklands war, which made Margaret Thatcher hugely popular. It was followed by Neil Kinnock of the centre-Left being elected leader. The Left was now destined for the political wilderness until 2015.

By then the young activists were the grizzled veterans who against all expectations fashioned the victory of the Left by using social media to attract new young supporters and by creating a political campaign based on repudiation of the Conservative’s austerity programme. The Left’s leadership plan in 2015, as in 1978, was to combine radical economic policy with a different form of politics based on listening to the membership. The veterans knew they could leave very little to chance.

When, in 2018, I interviewed McDonnell, he described how he felt about Corbyn winning the leadership, the lessons of the past and the urgency of taking power quickly and effectively:

“Get ready, start preparing now because what happens then is you realise after all those years in opposition on the Left, all those years of defeat and failure, the responsibility is on your shoulders, absolutely on your shoulders. And if you don’t get this right, the Left will be out for another generation. For God’s sake, we’ve got to get ready.”

And they have.

In 2015 McDonnell and Lansman created Momentum to have a permanent force of activists who could reinforce the leadership in both policy debates and in internal elections. By 2017 nine of the 39 places on the National Executive would be elected by the membership and the Left won all of them. This allowed them to take over the machinery of the Party such as the General Secretaryship and the committees running the disciplinary processes. In the clearest lesson learned from the days of New Labour, when parliamentary selections were rigidly controlled, the selection of Labour candidates in winnable seats is becoming the prime target of the Left.

The Left has succeeded beyond its wildest dreams in securing its dominance. It has the power and control over policy that it has always sought. It is creating economic policy that it believes will attract wide support from the electorate. It controls the machine. It has never had an opportunity like this.

So why the nervousness? Why does the fear of history repeating itself hang over it?

Despite three years of successes, the leader’s office have been faced with two issues it thought and hoped would either go away or be blamed on someone else. Anti-Semitism has become a deeper and deeper stain that isn’t being erased. Brexit has demonstrated the failure to demonstrate even a glimmer of Harold Wilson’s masterful tactics. The idea that Labour could push the blame onto the Conservatives and somehow appeal to both leavers and remainers has failed. The party has appeared weak, vacillating and confused. As the criticism has grown so the leadership’s position has hardened. The Left finds itself holding the levers of power but beginning to lose control of the internal authority it needs.

Everything will depend on a good result when the general election takes place, and the real fear is what happens if the Left is not up to the job of winning that election. If Labour cannot lead in the polls when Theresa May is Prime Minister and if in a European election it comes fifth in Scotland and third in Wales, then the prospects against a Conservative party with a new leader getting a “Boris bounce” do not look good.

If Labour loses, the Left has a huge problem. The veterans will be facing a leadership election in which Corbyn has gone and it has no winnable candidate to replace him. There is a generational gap between the sixtysomethings running the party and the new members of the shadow cabinet who are three decades younger. Rebecca Long Bailey, a protégé of McDonnell, would be the political heir but she would also face competition from candidates who would be much more in the tradition of the centre-Left.

Emily Thornberry, Angela Rayner, Keir Starmer or even Tom Watson could win the leadership as Labour faced five more years of opposition. The greatest fear of the Left is that one of them would be the new Neil Kinnock. The leadership would return to the centre. The Left would lose its influence, power and support. It would be 1983 again and the wilderness would beckon.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe