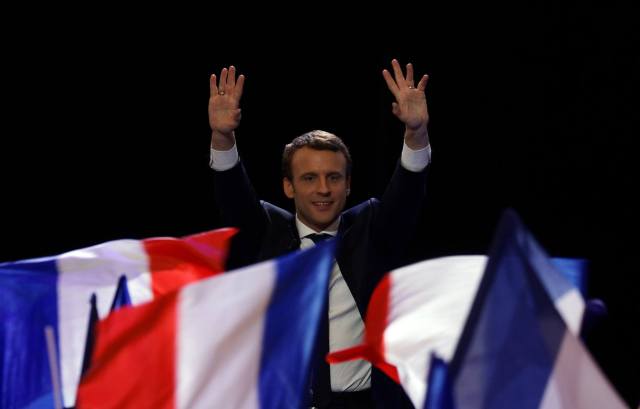

Credit: Sylvain Lefevre / Getty

All nations are exceptional but some are more exceptional than others.

The British, the Americans – and no doubt the Luxembourgers – are led to believe that they are blessed and distinct among the peoples of the world. And then there is France. French exceptionalism is exceptional.

The French are taught, like Americans, to believe that their nation represents, and even invented, universal values. Like the British, they are steeped from an early age in historic achievement and national entitlement. They acquire effortlessly an Italian sense of cultural superiority.

When President Emmanuel Macron said recently that it was time for France to “recreate the art of being French”, there was merriment abroad and puzzlement at home. When did the French ever stop being French? Why is being French an “art”? Is Frenchness not also an infinite capacity for protest, division and complaint?

After living in France for 22 years, and bringing up three children in the French school system, I have come to adore France and also to despair of France. I believe that there is a distinct quality of Frenchness – a way of dressing, an aggressively teasing sense of humour, a commitment to good food and pleasure but above all a particular French way of thinking.

France is a country which has many successes – from cars, to planes, to trains, to wine, to cheese, to health care, to clothes, to luxury goods, to perfume, to football – but loves to dwell on its failures.

France is not one place but many places, some hugely successful, others struggling. France sometimes confuses myths about itself with reality and often seeks to reform the myth instead of the truth. The Gilets Jaunes are guilty of that; so are many French politicians.

France is a country which is, en masse, prone to anger, pessimism and self-destruction but individually devoted to the pursuit of happiness. France is a country which is (mostly) proud of its past but often distrustful of the future.

So what did Macron mean?

Context is everything. He was talking 10 days after the calamitous fire which disfigured Notre Dame cathedral in Paris. He was announcing adjustments to his reform programme which he labelled “Act Two” of his presidency. He announced, in sum, that he planned to contain the five months old Gilets Jaunes rebellion by adopting a more “human” approach to doing what he planned to do anyway.

Here is a full passage from his comments during a two and half hour Elysée press conference:

“We must reconstruct together very profoundly what I would like to call the art of being French, which is a very specific way of being what we are. The art of being French is both deeply rooted and universal, to be attached to our history and our roots but able to embrace the future.”

“It’s an ability to argue about everything endlessly and it is, very profoundly, an ability to refuse to adapt to a world which escapes us, to refuse to yield to the law of the survival of the strongest and to pursue a policy of resistance and ambition, for today and tomorrow.”

Some French commentators said that this was not about the art of being French so much as the “art of being Macron” – a delight in spinning verbal webs which dissolve on contact. Maybe. But the abstraction of such comments is also quintessentially French.

Abstraction – love of the theoretical, the sweeping and the ideal – is hard-wired into the French language and the French character and therefore into French politics. It is a vital component in the “art of being French” and also a part, I will argue, of the “problem of being French”.

What Macron was attempting to achieve with these comments was three-fold. He was using the Notre Dame calamity to wrap himself in the cloak of France’s long history. He was implying that the restoration of French self-confidence and creativity was a sacred duty, like the restoration of Notre Dame. And he was trying to counter the impression – once encouraged by himself but now caricatured by the Far Right, the Far Left and the Gilets Jaunes – that he is a globalist who regards French national traditions and habits of mind as handicap and a misfortune.

In another part of his press conference, Macron called on the French to “work harder”. He suggested that part of France’s problem was that, on average, the French put in less time creating wealth than other countries.

With impeccable timing, a story emerged to backed this up. Australian engineers sent to France to work on a submarine programme for the their navy have been astonished by the long lunch breaks and extended holidays of their French counterparts. The Australians are used to taking a sandwich at their desks or drawing boards. The French insist on 90 minutes or two hours in a local brasserie.

An OECD survey last year showed – unsurprisingly – that the French spent more time eating and drinking in an average day, 2 hours and 13 minutes, than any other nation. The average is one hour and 30 minutes; Americans take one hour and two minutes.

And yet, the view that the French are somehow lazy or unproductive is wrong, as Macron himself has admitted. In terms of individual productivity, according to the OECD, French workers create more wealth per hour or per day than the Germans.

France’s real problem is that it has a smaller proportion of its adult population in productive work than other developed nations. Early retirement, high youth unemployment and interminable studies mean that France has barely 70% of its 16 to 65 population in work – compared to almost 80% in, say, Britain and Germany.

Macron said that he was not expecting individual French workers to put in longer hours by abandoning the official 35 hour week or to retire later than the present target age of 62. But he did not grapple with the core problem of how to enlarge France’s narrow, productive work force. Either suggestion would have produced an angry reaction from the moderate trades unions whose cooperation Macron needs to counter Gilet Jaune anger and boost economic recovery in the next three years.

This is a perfect example of how France finds its problems difficult to name or define, and therefore to solve. The country prefers to argue about myths than to confront reality. And the Gilets Jaunes are as guilty as anyone. They have some legitimate grievances but one of their principal complaints – that the rich don’t pay their way in France – is absurd.

Over 56% of French GDP is claimed by the state. The greatest tax burden falls on the rich. France has more “social transfers” from rich to poor, and rich areas to poor areas, than any other EU country. How efficiently such transfers are spent is another question.

Other countries elude problems. France mistakes what its true problems are. The French – and not just the intellectual French – like to construct a theory and then use it to explain the facts. Other nations like to examine the facts and then construct theories.

Sudir Hazareesingh, in his book “How the French think”, traces the phenomenon to 17th-century philosopher-mathematican Descartes and the 18th-century idealist Jean-Jacques Rousseau. British 17th and 18th-century thinkers believed in starting with observable facts. Descartes trusted only the deduction capacity of the mind. Rousseau believed in a perfectible ideal.

In France, Hazareesingh suggests, the theoretical construct is all. This explains, he says, why French of both Right and Left become so angry about something so seemingly unthreatening (to British eyes) as a muslim headscarf. The concept of the secular French state and the separation of state and religion is inviolable. Thus, a muslim girl wearing a headscarf in a state school or a muslim woman wearing a ‘running hijab’ to go jogging becomes an existential threat to the Republic.

There are, of course, exceptions to French abstraction and idealism. The French are great engineers and you don’t solve engineering problems by theories alone. The French commitment to l’art de vivre is far from abstract. It is physical and immediate – a quite separate strand of Frenchness which goes far beyond the wealthy and leisured classes.

My neighbours in Normandy, a retired car-worker and a retired cleaner, drive 40 kilometres to buy the right kind of mussels, or eggs, or piece of charcuterie. The early Gilets Jaunes roundabout protests turned into festivals of sausage grilling, with sheafs of fresh baguettes and a multiple choice of sauces.

But the abstract French cast of mind is also something which can be found across all classes and all regions. It suffuses the French education system, where kids are taught how to deconstruct sentences from the age of eight.

In all opinion surveys across France, the nation en masse is more pessimistic and dissatisfied than its individuals. Asked if their own lives are going well, French people are likely to say “oui”. Asked if the country is going well, they are almost certain to say “non”.

Personal life is about the immediate and tangible. Politics is about the theoretical and the ideal, which can never be attained. I am not sure that the French habit of mind can be blamed on Descartes and Rousseau alone. Why did French philosophers think the way that way in the first place?

The best explanation that I have heard came in an interview that I conducted a few years ago with Professor Michael Edwards, the only Englishman ever elected to the Académie Française. Professor Edwards is an acclaimed poet in both languages.

He says that he thinks differently – that he becomes a different person – when he is thinking or speaking in French.

English, he said, is a language which “grips reality”, which follows the contours of events just as an “English country lane follows the contours of the landscape”. France is a language, which “hovers over events like a hot-air balloon” – a more passive language, a more abstract language.

Let me push the argument further, at risk of becoming dangerously abstract myself. I believe the French language and French cast of mind create a predisposition for the ideal and the categorical. This feeds – and maybe partly explains – the French attraction to political violence and social anger.

In France, there is always a principle which has been betrayed; an ideal which has been trampled; an injustice to be fought; a heresy to be exorcised.

Charles de Gaulle famously said that it was impossible to govern a country which had 248 types of cheese. He underestimated the problem. There are over 500 types of French cheese – some people insist that there are over 1,000. What De Gaulle perhaps meant to say is that it is impossible to govern a country which is perpetually, perversely disappointed, a country which constantly demands change and rejects all changes.

If you look again at the passage from Macron on “recreating the art of being French”, he is wrestling with precisely these problems. How can you persuade such a quarrelsome, demanding nation to square globalism and Frenchness, tradition and modernity, protection and enrepreneurship, risk and continued social guarantees?

In the 50 years since De Gaulle disappeared from French political life, the French have voted for change, one way or another, in every national election but one. Their distrust of all politicians and all reforms has now been magnified by on-line halls of mirrors in the form of ‘anger sites’ on the internet.

But the problem is not new. The ‘art of being French’ and the ‘problem of being French’ were always facing mirrors. Rather than “reconstruct” the art of being French, Macron needs to find a way of deconstructing France’s myths about France, convincing France of its own achievements and reconciling France’s political pessimism with its everyday joie de vivre. Good luck with that.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe