Armenia is one of those countries just on the edge of people’s awareness. Blighted by one of the world’s first genocides, but blessed by the wealthy and vocal diaspora it created, it was the earliest national adopter of Christianity, and is the ancestral homeland to the Kardashian clan of Los Angeles. Armenia has always enjoyed that little bit more recognition than its post-Soviet peers.

Even so, in these troubled times, news of political turmoil anywhere in the former-Soviet neighbourhood is dumbed down to a mere calculation in the geopolitical chess game of the day. The Russians grimly mutter about the malign hand of George Soros, the Westerners rub their hands at the prospect of a new ally against the men in Moscow. Armenia is no exception.

However, as this tiny country of three million drew a decisive line under two decades of authoritarian rule, it showed that the only “p” word which applies to them is populism – not Putin.

For years, Armenia had been in a rut. Since independence, the country had scraped by economically on remittances from emigre taxi drivers, builders and waiters in Moscow, and politically by basking in the glory of victory over neighbouring Azerbaijan in the Nagorno-Karabakh War.

Governed by the Republican Party, which picks its politicians from entrepreneurs who need of parliamentary immunity to facilitate their business dealings, and chooses its leadership from ageing Karabakh War military commanders, Armenian political life was at a dead-end.

The opposition was little better: parliament’s second-largest faction, Prosperous Armenia, was described to me by one local as an ‘ATM’, built around the person of Gagik Tsarukyan, a flamboyant magnate with a penchant for boastful tax evasion. He has, according to the US State Department, ‘a personal style which would make Donald Trump look like an ascetic’.

Consistently unfree elections, involving vote-buying and coercion (or, as the local euphemism has it, ‘administrative resources’) had seen anti-system radicals take to the streets. But although Armenia’s politicians were unpopular, they were unmoveable. So public protest was the opposition’s only voice, and these would spring up every so often in response to rigged elections, hikes in utility prices and urban development schemes.

The inert politics inevitably created an unjust economy. After almost 30 years of independence, Armenia remained desperately poor, even by regional standards. Its well-educated, but chronically underemployed population had to suffer the indignity and dislocation of seeking precarious, low-status work abroad, usually in Russia. Stints in Moscow, were pervasive racism and low wages had to be endured, were a rite of passage for young Armenian men.

Meanwhile, an oligarch class even more conspicuous in its spending and, it is often said, criminal in its activities, than its equivalents abroad parlayed its political connections into securing wildly lucrative import and export monopolies on basic commodities: grain, oil, metals. As one protestor at a sit-in in Yerevan, the capital, told me, “We’re just sick of a few people owning every-fucking-thing.”

Armenia, in short, was being buffeted by those same forces that drove populist uprisings in the West. Years of grinding poverty, massive economic inequality, a distant political class, even the social impact of mass (e)migration had left the regime with almost no active supporters.

Though it may have been outwardly unexpected, Armenia, as we now know, was a bomb ready to go off.

Not that Serzh Sargsyan, the uncharismatic Karabakh commander, turned defence minister, turned prime minister, turned president, realised. He was oblivious to the nearness of his political grave. As was the ruling ruling elite; they had plans to keep themselves and Serzh firmly in office. These took the form of a neat little power move that Putin would have been proud of: after some finessing of the constitution, president Sargsyan was going to assume the enhanced, more powerful, position of prime minister.

But they had reckoned without Nikol Pashinyan.

Populist uprisings tend to have suitably populist leaders, and Armenia is no exception. In 2017, Pashinyan, a former newspaper editor, just about squeaked into parliament at the head of a small coalition of liberal parties. At which point pretty much everything about him changed: out went suited and booted bourgeois intellectual chic, in came camouflage T-shirts, baseball caps, and a flyaway beard. It was as if Alan Rusbridger had become Fidel Castro.

It was in this new guise, as the dynamic, military, man of the people, that Pashinyan called for protests against Serzh’s new lease of political life.

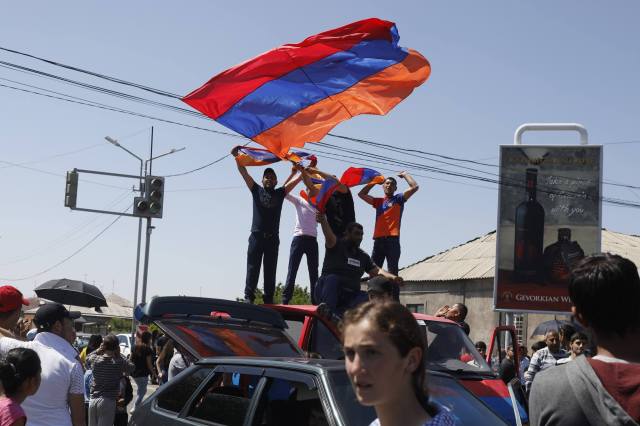

The scale of the people’s response confounded everyone’s expectation. The unexpected revolutionaries who stopped the traffic were a mixed bag: students with dyed hair, oversized glasses and fluent English, marched alongside weather-beaten, Russian-speaking pensioners. They all mingled with soldiers and once the speeches were done with, the rallies transformed into impromptu hip-hop concerts in Republic Square.

Then, when Pashinyan was briefly jailed, the sheer weight of popular pressure saw him released within a day. Soon after, unable to see a way forward, Serzh himself bowed out, heading off into comfortable retirement.

His Republican Party, described to me by one local analyst as not much more than a trade union for regime-minded bureaucrats and entrepreneurs, put up a desperate fight, playing for time, hoping the protestors might eventually give up and go home.

But they didn’t. And yesterday parliament, still dominated by the flamboyant oligarchs and grey bureaucrats of the old guard, finally appointed Nikol Pashinyan, the crusading liberal journalist, as its new leader.

But this populism is not only for liberals: Pashinyan’s movement has been careful to reach out across class, cultural and social boundaries. After his release, he spent two days touring Armenia’s small towns and cities receiving the sort of response usually reserved for an evangelical preacher. In a country like Armenia, anti-establishment populism is a uniting force.

And as with populists anywhere, the expectations are high and the odds long: Nikol, people told me, will end corruption. He’ll run the oligarchs out of town while raising wages so no one has to emigrate.

With Nikol now catapulted into the premiership, everyone, from liberals and Stalinists to feminists and theocrats, is eagerly awaiting the Armenia he will create, each sure it’s the one they’ve always wanted.

The story of crusading post-Soviet reformers taking on oligarchy and corruption is a story that has already played out in Georgia and Armenia. It’s rarely ended happily. Armenia’s road will be long, hard, and possibly without any ending, happy or otherwise.

But that hasn’t dampened spirits. As one local activist, no friend of Nikol Pashinyan, told me in the days after Serzh’s resignation, “If Nikol tries to do what Serzh did, he’ll know we can throw him out, too.”

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe