Credit: georgeclerk / Getty Images

With ministers finally contemplating bold action to tackle the UK’s dysfunctional housing market, the “iron triangle of vested interests” – large developers, leading UK banks and millions of property-owning voters – are becoming increasingly concerned that their cosy status quo could soon be disrupted.

Senior housing industry executives have tried to downplay the link between historically low “completion” rates and sharply rising unaffordability. In 2016, for instance, the Redfern Review highlighted that increasing the supply of housing “does not directly improve the home ownership rate”.[1. ‘The Redfern Review into the decline of home ownership’, 16 November 2016. Peter Redfern is Chief Executive of Taylor Wimpey, one of the UK’s largest house-builders.]

Some economists, such as Ian Mulheirn, have gone further , suggesting “there is no housing shortage” and “the obsession with supply is a red herring”.[2. Ian Mulheirn, ‘Building more homes won’t solve the housing crisis’, CapX, 6 February 2018] These claims are now being repeated by prominent political commentators.[3. Matthew Parris, ‘There is no housing crisis – it would be easier if there were’, The Spectator, 10 February 2018 ]

Crisis? What Crisis?

The central plank of Mulheirn’s argument is that Whitehall has been producing “repeatedly exaggerated” official forecasts of household growth. Since 2008, UK household formation has averaged only 152,000 per year, he points out, far below the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) estimate of 235,000. The implication is that because around 80,000 fewer households were formed each year than policymakers expected, the housing supply shortfall is being overstated.

Yet the reason fewer households are being formed than officially predicted is because, for many people, the necessary physical home to create that household is unaffordable – either to rent or buy. Such people still exist, though, and often end up either living with their parents as adults, or as part of a “concealed household” not counted in official numbers.

From 2006 to 2017, the number of 20-34 year olds living with their parents increased 28%, from 2.65 million to 3.4 million people – including 20% of women in that age range and an astonishing 32% of men.[4. The raw numbers can be accessed at ONS Table ‘Young adults living with their parents’] Some adults in this age range may willingly choose to stay with their parents. But, as housing has become less affordable, the share doing so has risen from a fifth in the mid-2000s to a quarter in 2016. It can surely be assumed that a significant number of the 750,000 rise in 20-34 year olds living in their parental home over the last decade are doing so because they are unable to rent or buy.

The rise in “concealed households” (where at least two adults live within another household) during the ten years to 2016 has also been very significant, rising 50% to 2.5 million. In London alone, concealed households rose from 400,000 to 720,000.[5. These numbers, also 2006-2016, are based on the Labour Force Survey, and quoted in an unpublished MHCLG memo obtained by the author] Again, while some couples may choose to live within another household, it seems reasonable to assume the vast majority are doing so as they lack the means to buy or rent to form a household of their own.

Given that each concealed household comprises at least two adults and some couples will have children, well over some 2.5 million people under these two headings are currently living in the UK who – in many cases against their wishes – have over the last ten years not formed the “households” that officials previously predicted they would form. They are unlikely to agree with Mulheirn’s conclusion that “UK housing needs look to be far below [official] forecasts”.[6. In 2015, evidence submitted to the House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee inquiry ‘The Economics of the UK Housing Market’, highlighted the danger of under-estimating the ‘concealed households’ levels, whereby “young adults, couples and mothers with children {are} continuing to live with parents, young adults {are} trapped in sharing and mature adults {are} obliged to share”. See House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee, ‘Martin Grubb: Written Evidence (EHM0066)’, p 558. See also Daniel Bentley, ‘Housing Supply and Household Growth, National and Local’, Civitas Briefing, December 2016: “An under-supply of homes is likely to curtail the number of households actually formed … This may take the form of young adults not moving out of their parents’ home when they previously would have done, or people joining house-shares, or people becoming homeless. Even if those households are not actually formed, however, the pressure for housing will remain]

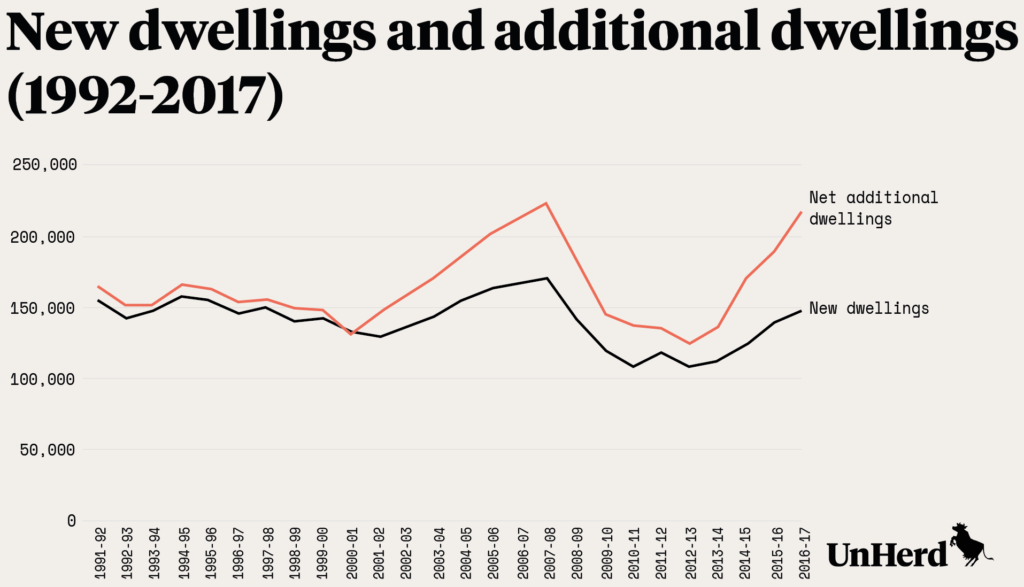

The second main pillar of the “no shortage” argument highlights that the number of homes being built is lower than “net additional dwellings” – which includes conversions of houses into flats, and shops and offices into homes. As such, while housing “demand” is over-stated, “supply” is under-stated because there are more new homes once conversions are included. Once you combine these two effects, Mulheirn argues, “there is no shortage of homes”.

It is certainly true, as shown in the graph above, that the number of “net additional dwellings” has recently pulled significantly ahead of “new dwellings” – that is, the number of newly built homes. A major reason is that in 2014, “automatic permitted development rights” were granted to convert offices into residential properties – and since then “change of use” additions to the housing stock have nearly doubled, from around 20,000 in 2006/07 to 37,000 in 2016/17. While there were 147,930 new homes completed in England in 2016/17, then, there were 217,350 net additional dwellings.[7. MHCLG Table 209 ‘Permanent New Dwellings Completed’ and MHCLG Table 120 ‘Net Additional Dwellings’]

Sometimes, converted shops or office buildings can indeed make suitable, even attractive, additions to the UK housing stock. There is certainly merit in encouraging “change of use” as the government has done, not least in city centres where demand can be acute. Some schemes may end up revitalising certain neighbourhoods.

But that does not mean that “net additional dwellings” are, as Mulheirn argues, “the bigger picture”. Yes, we are in the midst of a conversion boom, but that does not amount to a permanent upward shift in the long-term rate of UK house building. For one thing, the sharp rise in conversions over recent years is largely due to the one-off 2014 legislative change.

As the Nationwide Building Society has pointed out, the current high conversion rate is likely soon to fall away as the availability of commercially attractive sites reduces. Changes of use from existing premises are, by definition, finite. “While this is an encouraging development, we shouldn’t overstate its significance,” says Nationwide. “The growth in ‘change of use’ may well slow in future years, as developers have probably converted the easiest sites and the stock of suitable commercial property will reduce … the quality and long-term suitability of some of these changes of use remains to be seen”.[8. ‘Is this the answer to the UK’s housing problem?’, Nationwide Blog, 6 December 2017]

On top of all this, the “no shortage” argument is based entirely on national numbers, ignoring that many homes, new and existing, are in the wrong place, a long way from where people work. Aggregate housing data takes no account of the local bottlenecks – either in planning or “build-out” once permission has been given – that create supply imbalances in areas where homes are needed most.

Those asserting “no shortage” sometimes point to the number of empty homes as evidence for their case. Yet, again, many empty homes are a long way from where people live and work. And while there were around 300,000 homes in England standing empty for over six months in May 2010, there are now around 200,000 – a decline of a third. This represents just 0.8% of the total housing stock, the lowest since records began.[9. This is an area of relative housing policy success, with local authorities having been given powers and incentives to tackle empty homes. As part of the “New Homes Bonus” introduced by the Coalition government, councils earn the same financial reward for bringing an empty home back into use as building a new one. They also have flexibility to impose a council tax premium of up to 50% (on top of the council tax bill) on properties empty for over two years. Powers to raise that premium to 100% of council tax were announced in November 2017] Of course, more should be done to bring empty homes back into use. But the number of empty homes has fallen sharply over the last decade, as affordability has become worse – suggesting the reason that millions of young adults are “priced-out” of UK property lies elsewhere.

A convenient narrative

There is clearly a willing and receptive audience, a market in fact, for the “no shortage” argument. For those opposed to a significant rise in UK house building, including powerful developers and some environmental campaigners, it provides a convenient narrative. These lobby groups can then claim nothing needs to be done to address unaffordability – or, at least, nothing that involves building more homes. It is wrong, though, to interpret lower than expected household formation rates as evidence of less demand and need for housing. And a one-off “change of use” conversion boom by no means amounts to a structural increase in the output of an industry dominated by a few powerful developers who benefit massively from “contrived scarcity”.

Another debate that has recently flared up is the impact of immigration on house prices, with Housing Minister Dominic Raab arguing that immigration has pushed up property prices by 20% over the past 25 years.[10. ‘Minister Dominic Raab told to publish proof that immigration raises house prices’, The Times, 9 April 2018 ] Pro-immigration commentators have countered with reference to an authoritative 2011 investigation that found: “The impact on house prices of the accumulated increase in Tier 2 type (skilled) immigrants over a five-year period is likely to be well below one per cent”.[11. Christine Whitehead et al., ‘The impact of migration on access to housing and the housing market’, LSE/Migration Advisory Committee, December 2011] Another study concluded that, at the local level, immigration may reduce house prices slightly – as the arrival of relatively less affluent immigrants in an area lowers prices buyers are willing to pay.[12. Filipa Sá, ‘Immigration and House Prices in the UK’, IZA DP No. 5893, July 2011]

While Raab is a long-standing advocate of the merits of immigration, he appeared to be arguing that significantly lower net immigration after the UK left the EU would ease the housing crisis. “You’ve got to deal with demand as well as supply,” he said. “If we delivered on the government’s target of reducing immigration to the tens of thousands every year, that would have a material impact on the number of homes we need to build”.

The large number of new arrivals in recent years has certainly added to the pressure on the UK’s woefully inadequate housing supply. But immigration, while impacting poorer local communities disproportionately, has been of overwhelming net benefit to the UK economy, in terms of both fiscal balances and broader growth.

Britain has a housing supply problem, and a related affordability crisis, not because of immigration but because, over several decades, the UK housing industry, housing associations and local authorities between them have failed to build enough homes. The UK is now building at a rate each year equivalent to just 0.49% of the existing housing stock, down from 0.7% in 2000. That places Britain 27th out of 31 industrialised nations, according to the OECD. The UK is behind Lithuania, Estonia and Cyprus when it comes to house building, ahead of only Latvia, Portugal, Bulgaria and Hungary. [11. ‘Housing Stock and Construction’ Social Policy Division – Directorate of Employment, Labour and Social Affairs, Organisationfor Economic Cooperation and Development: Paris, August 2017]

Net migration into the UK has clearly soared over the last 20 years. From 50,000 in 1997, net inflows rose to over 330,000 in 2016, at the height of the EU migrant crisis, before falling to 244,000 during the year to September 2017. There has been a failure to put in place adequate provision in terms of schools, hospitals and housing – leading to understandable discontent among some communities particularly reliant on scarce public services, even those with a history of relatively successful immigration absorption over previous generations.

Even if net immigration were to fall below 100,000 in the coming years, as Raab says it should, that would do almost nothing to address the chronic shortage of homes that has built up since the mid-1980s. Net migration could fall to zero, but there would still be millions of concealed households, serious over-crowding and a nationwide lack of affordability. Too tight or too rapid a restriction on immigration could in fact do harm when it comes to building the homes needed to ease the shortage, given the significant role previous waves of semi-skilled immigrants have played in earlier UK house-building booms.

The government cannot use the excuse of lower immigration to dodge the bold and, to some interest groups, possibly uncomfortable action needed to revitalise the supply side of the UK housing market.

It is clear to the vast majority of analysts working in this area that the UK is suffering from a chronic shortage of homes. There are many vocal interest groups that want to prevent an increase in UK house building – and they are no doubt a willing audience for, and will vigorously promote, “no shortage” claims. But such arguments – whether they result from genuine and well-meant research, or as part of a lobbying effort by large developers – are disproved by a cool analysis of the facts.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe