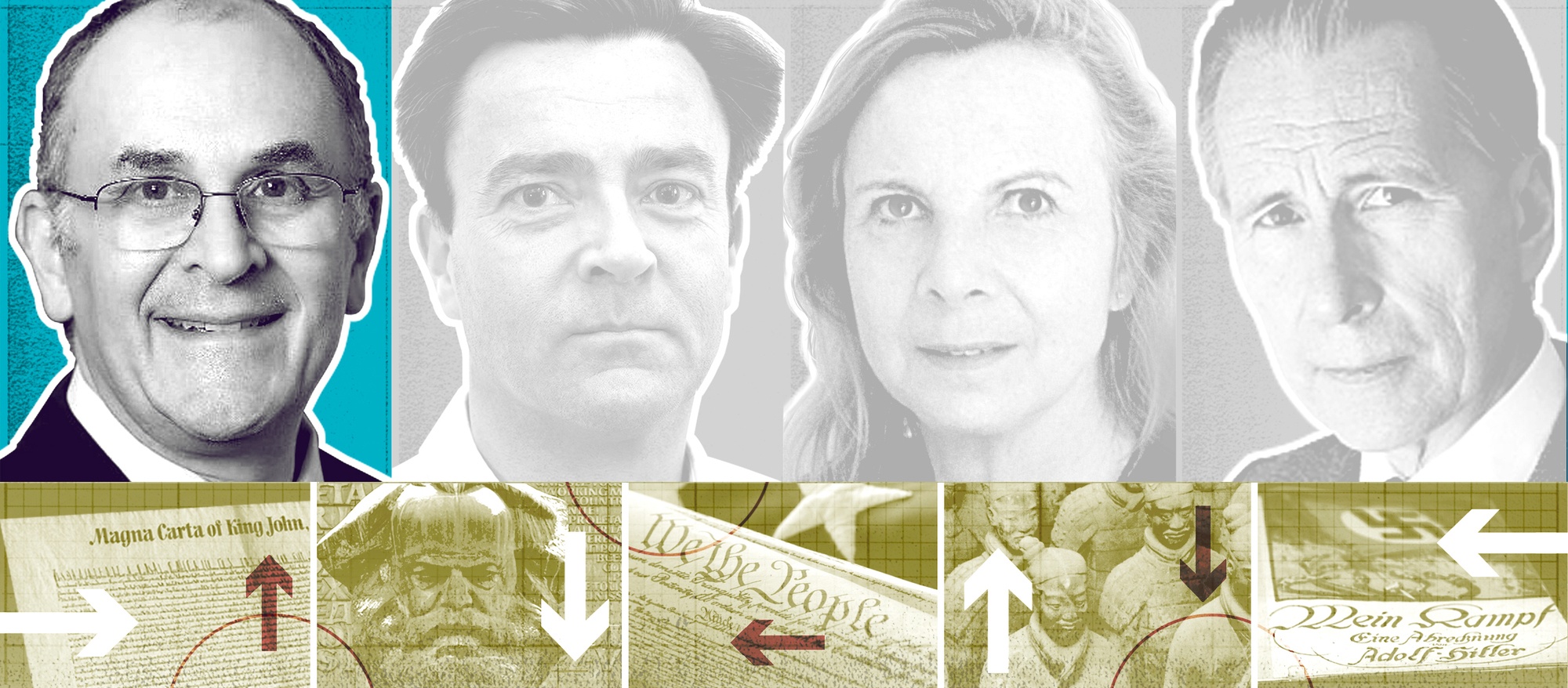

Slightly later than promised – here are the first verdicts of UnHerd’s new History Jury – as previewed last week by Allan Mallinson.

Tomorrow the jury will reassemble to answer the question, “What “event” of 2017 will in the long-run prove far MORE consequential than currently supposed; and why?” (Added: Here are their answers).

ELIOT COHEN: TRUMP’S JERUSALEM DECISION

President Trump’s decision to officially recognise Jerusalem as Israel’s capital produced the expected quotient of gasps, head-shaking, and finger-waving from the establishment. Even for those of us who loathe the man and are inclined to oppose anything he does simply because he does it, it has already turned out to be a forgettable moment. In so doing it is a reminder that is only when an absurd policy collapses that we can see just how silly it was all along.

Behind the unwillingness to officially recognise Jerusalem as Israel’s capital lay not the unresolved issues of Israeli-Palestinian peace and sovereignty over territories occupied and administered by Jordan until the Six Day War in 1967. Rather, it originated in the original, and very dead, partition plan of 1947 which proposed an international status for the Holy City. Since Israel’s parliament, foreign ministry and prime minister’s office are all in the western part of the city – which everyone assumes will stay Israeli no matter what – the policy was senseless.

Indeed, what was striking was just how indifferent Cairo, Riyadh, and Abu Dhabi (among other Arab capitals) were to what happened to Jerusalem. Perhaps what was important, though not consequential, was the manifestation of a simple reality: other conflicts and developments in the Middle East matter a lot more than whether external powers recognise a seventy year old fact.

PAUL LAY: BREXIT

PAUL LAY: BREXIT

Brexit will be of less consequence than one might expect from Britain’s obsessive media coverage, made worse by the Manichaean world of social media, where recriminatory wishful thinking marks the extremes on both sides. The UK and the 27 EU nations are friends, allies and – most importantly –trading partners, and will remain so.

The negotiations will be fraught, even unpleasant on occasion – that is democratic politics – but both sides have a fundamental interest in reaching a relatively amicable and reasonable solution. Once that is achieved, one hopes that the UK will finally address its deep-rooted problems: a poor technical education system and a crass public sphere. Similarly, the EU should concentrate on the challenges of immigration and the rise of far-right ideologies among the Vysegrad countries (and, to a lesser extent, in France, Germany, Austria and the Netherlands). Germany faces an existential challenge, too: how does it transform itself – urgently – from a manufacturing powerhouse of hardware into one fit for the Fourth Revolution? It is a long way behind Silicon Valley, Israel and the other software pioneers, and it is not helped by the instability following Merkel’s unmasking.

If anyone will be harmed by Brexit, it is most likely to be the Republic of Ireland, though even that, in the long term, may result in a united island, which will be largely welcomed in Britain, but create anxieties, not least economic ones, in Ireland. Those six counties are expensive.

VICTORIA SCHOFIELD: MUGABE’S ‘END’

The fall of President Robert Mugabe will prove less momentous for the twenty million Zimbabweans (including four million exiles living in South Africa and the UK ) than at first anticipated.

For decades Africa watchers have lamented the iron hold which the 93-year old Mugabe retained on Zimbabwe since independence in 1980; supported by the Zimbabwe National Army (ZNA), he ran the country as a one-party state. When news broke in November 2017 of his forced retirement, brokered by the same military who had sustained his authority, Zimbabwean politics appeared to be at a turning-point. There were high expectations that the people could look forward to a more democratic form of government, with checks and balances on presidential authority and a more harmonious relationship with the minority white population. The symbolic return of the Zimbabwean white farmer, Robert Smart, one of several thousand evicted from their lands during the Mugabe regime, was indicative of a more benign approach.

But it now appears that the new government of President Emmerson Mnangagwa, who also depends on the support of the ZNA, will replace one style of dictatorial rule by another (Presidential ‘elections’ next September notwithstanding). There is to be no truth and reconciliation and no accountability for Mugabe’s excesses. Instead while the former President enjoys a generous retirement package at state expense, the same autocracy, nepotism and human rights abuses will continue.

ALLAN MALLINSON: NORTH KOREA’S NUCLEAR AMBITIONS

A historian’s business is the past, not the future. That said, if journalism is the first rough draft of history, it’s perhaps legitimate to comment on how that draft is written.

“In the long-run we’re all dead” (Keynes), but let’s define the long-run as the next ten years. And in that time, despite the advances in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea’s nuclear weapons technology (specifically, miniaturisation of a nuclear detonator) this year, and testing of an “intercontinental” ballistic missile, I do not believe, as some fear, we shall see war on the Korean Peninsula. (I’d prefer to say “should not”, but the question to the jury isn’t phrased in the conditional).

Here’s why I don’t envisage a war. First, it’s not in China’s and Russia’s interests that the DPRK develops a credible capability, since that would change respective relationships with the DPRK to their disadvantage. Equally, it’s not in their interests that the US resorts to arms to prevent the DPRK developing that capability, for besides the law of unintended consequences, it would mean the ultra-long-term intrusion of the US into East Asia, and the border of an enlarged Republic of Korea on the Yalu River.

Above all, war isn’t in the DPRK’s – and specifically Kim Jong-un’s – interests. The DPRK’s forces are equipped and trained for conventional, not guerrilla, warfare, and would be as roundly defeated as were Saddam’s in the Gulf War. (And I do not think that, given the purpose for which the US would go to war, the US would shrink from using tactical nuclear weapons if necessary). Kim is not irrational. His nuclear programme is almost certainly based on the same logic as Nato’s during the Cold War: if conventional forces are too expensive, rely on nuclear. He has a growing middle class, and the universal vice – or virtue – of the middle class is materialism. Kim’s long-term aim is regime survival. He will probably not have much Latin, but he will know the import of “Sic semper tyrannis.” Certainly, friends in China will be able to tell him about the fall of the unassailable Robert Mugabe after Zimbabwe’s General Chiwenga visited Beijing for “consultations.”

I don’t rule out pre-emptive strikes, or some very nasty surrogate bloodletting, but regional war? No.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe