Credit: Jonathan Herbert I JH Images

“Look through history. Where the gospel is preached, other freedoms follow. The abolition of slavery led by evangelical Christians, most notably Wilberforce, the laws to prevent industrial exploitation led by committed Christian Lord Shaftesbury…”

So claimed Tim Farron MP, the former Liberal Democrat leader, at the Theos Annual Lecture last week (28 November).1 Writing for UnHerd, Danny Kruger described it as one of the bravest speeches he’s heard from an MP.

Farron’s lecture was essentially a defence of Christianity within the liberal tradition, his argument being that not only has “good” sprung from the Faith, but also that to say there is no place for Christianity within liberalism – because Christianity requires belief in the transcendent rather than the relative – is itself inherently illiberal.

There are problems with this, of course – at what point, for example, are less than wholly liberal views to be denounced? – but Douglas Murray praises Farron for understanding the difference between what he calls convening liberalism (where all reasonable voices are at least respected) and a campaigning liberalism that, more rights-based, secular and left-leaning, allegedly wants to be very dominant top dog at the expense of other ideas.

Farron believes, no doubt correctly, that he was invited to speak because of his defenestration as party leader, though in fact he jumped before he was pushed. He jumped, he said, because the LibDems were no longer the second party of Opposition (the Scottish National Party having greatly more MPs) and he therefore struggled for media time, and that the focus on his Christian beliefs prevented him from making the important political points required of a leader of a political party.

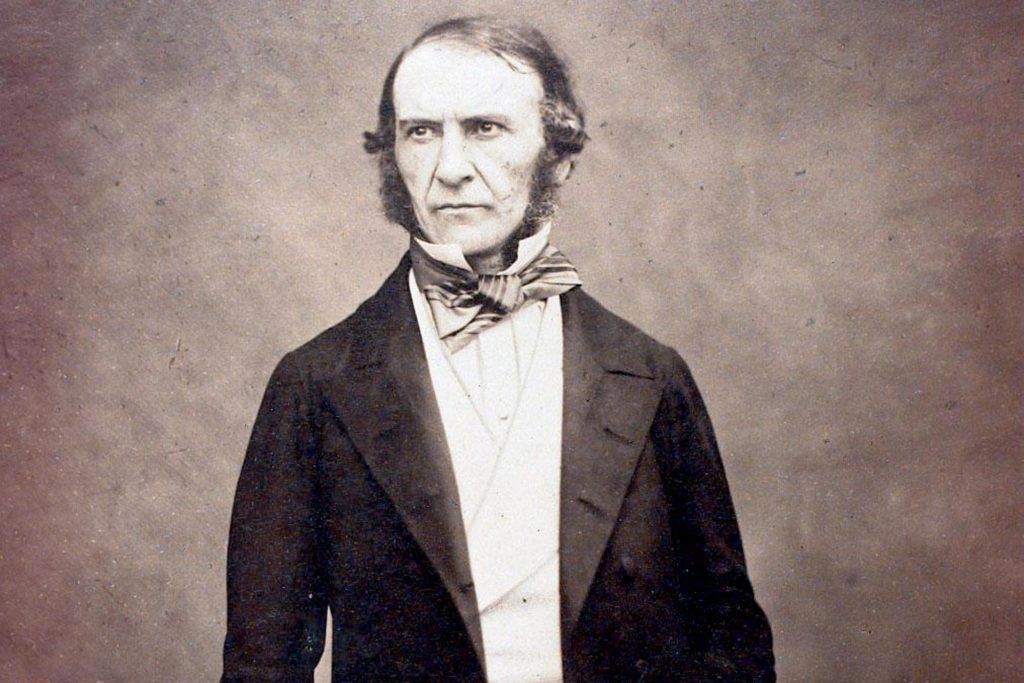

Being suspicious of political leaders who take orders from God is not a new thing for the British, however – and especially the English. Even the saintly William Wilberforce, an (independent) MP from 1780 to 1825, who declared that “God Almighty has set before me two great objects, the suppression of the Slave Trade and the Reformation of Manners [moral values]”, was subject to the ridicule that befell members of the aristocracy and gentry who proclaimed their evangelical principles.

With just cause?

Yet England had a right to be suspicious of leaders who believed they were ordained by God (Cavaliers) or compelled by Him (Roundheads). Some 200,000 men, women and children out of a population of 3.75m had perished during the English Civil War (1642-51), a conflict with, at its heart, the question of Divine authority exacerbated by sectarianism. Little wonder that at the Restoration in 1660, Charles II was keen to see an inclusive Church of England and latitude towards Catholics and protestant dissenters. He distanced himself from the doctrine of the Divine Right of Kings, and consequently the rhetoric of Divine guidance was generally much diminished in public life.

Through most of the 18th Century, indeed, the Church of England languished as “the Tory Party at prayer”, the one not troubling the other’s conscience much in matters of faith, morals or social responsibility, while the Catholics on the whole lived quietly and apart, no longer persecuted but still regarded with suspicion. It was Wesleyan Methodism, with its emphasis on moral regeneration and good works, that troubled the waters. Originally a movement within Anglicanism, after John Wesley’s death in 1791 it split from the C of E to become yet another dissenting church, its adherents thereafter excluded from public office.2 However, the split gave a boost to non-conformism, not least because many Methodists were men of standing.

Despite the Methodists’ defection, though, evangelical concern for the moral reform of society had entered the mainstream of public life, most notably and perhaps most importantly in the movement to abolish slavery. Wilberforce himself remained in the C of E and became a prominent figure in the network of Anglican evangelicals called the “Clapham Sect.” The Claphamites were heartily disliked by many a churchgoing Tory (and Whig, for that matter), uncomfortable with evangelical fervour in worship and mistrustful of radical social reform (In 1831 virtually the entire bench of bishops opposed the parliamentary Reform Bill). Since the Civil War, political leaders had kept their piety under strict regulation. Indeed, it had become somehow un-English to do otherwise.

A Christmas Carol (and other stories)

Things began to change in Victoria’s reign with increasing urbanisation, a growing middle class (and middle class franchise), and a press which began taking an interest in the condition of the poor (Dickens was first a journalist). But social concern stemming from religion was boosted mid-Century by the “Oxford Movement”, which in trying to recall the Anglican Church to its Catholic roots emphasized the pre-Reformation doctrine of “Justification by Good Works” rather than simply by “Faith.” Anglo-Catholic clergy became prominent in the poorer city and industrial parishes, and the movement as a whole – not least because its clergy were often from influential families, the great schools and Oxford – began to “make converts” in public life. Most notable of these was Gladstone, four-times prime minister.3

But Gladstone’s troubled public conscience also troubled others, who disliked his “preachiness.” Queen Victoria was irritated by the way he “addresses me as if I were a public meeting.” In 1838 he had nearly ruined his career by trying to force a religious mission on the Conservative Party. Disraeli made capital of Gladstone’s Anglo-Catholicism, suggesting that he was in fact a crypto-Papist – or, at least, a supporter of diabolical papist activities such as ritualism. The Third Marquess of Salisbury, a devout and thoughtful Anglo-Catholic (he helped found Pusey House in Oxford) who succeeded Gladstone as prime minister in 1885, was not slow to draw the conclusion that public piety could be misconstrued. His public utterances were duly guarded.

Twentieth-Century Foxes

Certainly David Lloyd George, Liberal chancellor of the exchequer 1908-15 (and then prime minister – and known occasionally as “the fox of London”), did not hide his non-conformism during his reforming budgets, but neither did he proclaim it. He had enemies enough without making more. When he did “preach” it was always in his native Wales, and, sensibly, in Welsh.

The First World War generated a certain “muscular Christianity”, and out of respect for the dead there emerged for a time a greater respect for the established church, which had somehow to represent the nation in its obsequies and memorializing, but between the wars the C of E, with a few notable exceptions, lapsed once more into comfortable Erastianism. Politicians seemed disinclined to bring God into the debate, although there were men of considerable personal piety. Lord Halifax, foreign secretary just before the Second World War, was dubbed by Churchill the “Holy Fox”.

Stanley Baldwin, three-times prime minister between 1923 and 1937, was personally devout – convinced, indeed, that he was an instrument of the Almighty, though as several writers have remarked, what the Almighty used him for was not so evident to others.

In July 1940, while still foreign secretary, Halifax gave a powerful radio address extolling the power of prayer:

“We may take heart from the certain knowledge that that great people [America] pray for our victory over this wicked man and his ways as fervently as any of his present victims. The foundations of their country, as of ours [emphasis added], have been Christian teaching and belief in God.”

Afterwards, Baldwin sent him a long and appreciative letter in which he wrote how for “prayer to be effective [it] must be in accordance with God’s will, and that by far the hardest thing to say from the heart and indeed the last lesson we learn (if we ever do) is to say and mean it, ‘Thy will be done.’’4

Post-war Reconstruction

After the war, politicians just “got on with it”, for there was undeniably much to do. Clement Attlee, Britain’s first post-war prime minister, was not a practising Christian, although one of brothers had been ordained, and one of his sisters was a missionary. When asked once whether he was an agnostic, he replied, with characteristic dry wit, “I don’t know.”

Harold Macmillan (prime minister 1957-63) was an Anglo-Catholic who might have crossed the Tiber had it not been for his mother, but he rarely invoked God in his speeches. They were on the whole well enough received without risking it. Margaret Thatcher (1979-90) was far less circumspect. Her strong religious background and faith was central her personality, thinking and politics, and she had no qualms about drawing on the Bible in her speeches (in more biblically literate days). Famously, outside No 10 on the day she became prime minister, she said:

“I would just like to remember some words of St. Francis of Assisi which I think are really just particularly apt at the moment: ‘Where there is discord, may we bring harmony. Where there is error, may we bring truth. Where there is doubt, may we bring faith. And where there is despair, may we bring hope.’ ”

The words were not welcomed by all, however, because Thatcher herself wasn’t. It was probably one of the reasons why Alistair Campbell, Tony Blair’s director of strategy and communications, who was unable to separate the man from the message, told an interviewer in 2003 who asked Blair about his Christian faith, “We don’t do God.”

In fact, in telling Blair not to “do God”, Campbell probably did a great deal more to propagate the Faith than the answer the journalist would otherwise have received.

Yesterday on UnHerd, Elaina Plott looked at how the politics of the Bible Belt still appear to rule in Alabama. Some things just don’t seem to cross the Atlantic well, one of which is God in politics.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe