Young people have suffered immensely during the pandemic. A 70% spike in demand for mental health services, a rise in financial insecurity and accounting for over 80% of the jobs lost in the past year have all contributed to feelings of isolation, alienation and despair. Now, as double vaccinated adults book their summer holidays, the young must again wait.

Small wonder, then, that the pandemic has accelerated a collapse of social trust among young people. According to a new report by Onward, the proportion of under-35s saying they have just one or no close friends has trebled in 10 years, from 7% to 22% while the share with four or more has fallen from 64% to 40%. Compared to just 20 years ago, under-35s are half as likely to say they regularly speak to neighbours and a third less likely to borrow and exchange favours with them.

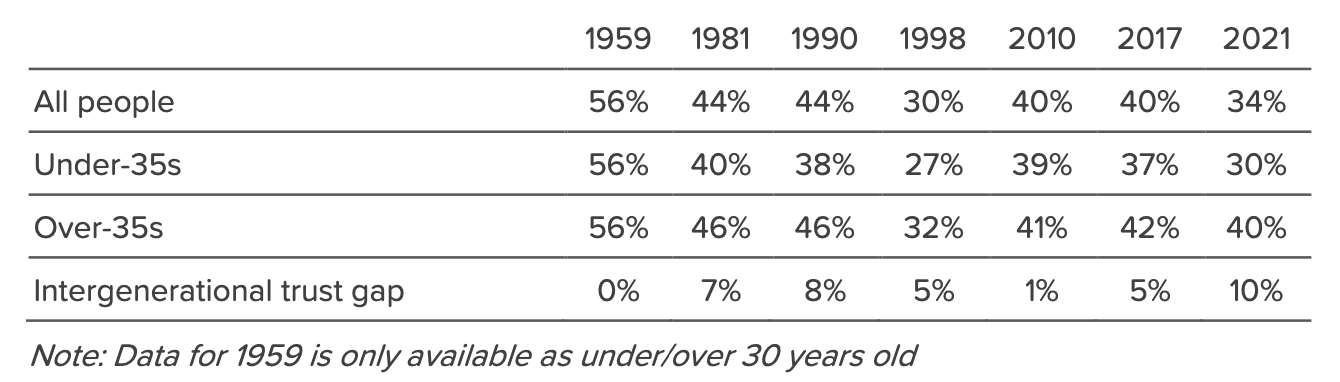

The authors of the report state that the pandemic has contributed to an ‘epidemic of loneliness’ among young people, which chimes with an ONS report earlier this year that found those areas with greater concentrations of young people to have higher rates of loneliness. It is a bleak picture and one that long predates lockdown:

According to the authors, these figures reveal a “paradox of virtue” where:

There are, of course, familiar culprits: social media, a lack of job opportunities, rising housing costs and student fees. These are problems that have existed for a better part of a decade and the frustration for young people is that no one seems to be listening. This is perhaps best captured by the boomer-led “Great Reset” movement and its attendant slogan “you will own nothing and you will be happy”.

Implicit in this slogan is the idea that if we could just rewind the clock 16 months, all will be well again. But there are serious, structural disadvantages facing young people that have not been adequately addressed — if at all — by this Government or any before them. Until they do, the young will start to become more politically unpredictable, the signs of which are already emerging: millennials and Gen Z are the most authoritarian out of any generation and, as a report from the IEA found this week, over two-thirds prefer socialism over capitalism.

Onward’s authors do make some proposals, ranging from the introduction of a national civic service — in which every young person undertakes 10 days of voluntary activity each year — to building half a million new homes for young people. But these are only small steps in the right direction. For bold, systemic change to take place, it will have to occur at a Government level. If only there was a Prime Minister with an 81-seat majority and a level-up programme who could do something about it…

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeIf there is a real increase in depression among our youth (as opposed to an increase in the tendency to claim that you are depressed to pollsters) maybe the monumental increase in divorce and separation is the real culprit. 50% of marriages now end in divorce (that’s without counting the parents that split up without marrying). I have never met a child whose parents got divorced who wasn’t traumatised by the experience and i expect that trauma lasts far into adulthood. I would think this is far more likely an explanation for “feelings of alienation, isolation and despair” than housing costs, the job market, social media or vaccine disparities. I suspect it is not discussed because divorce is now so common that society can’t face up to the pain we have caused our kids. Far easier to blame “structural disadvantages”.

I’m not sure that there is something cumulative going on too. When I worked as a Street Pastor 8-10 years ago we would regularly encounter groups of up to 20 teenagers hanging out in parks. Over the following few years these groups just dissipated. I concluded that it was the rise of social media – Instagram, Snapchat, FaceTime, etc. Instead of having to travel somewhere especially in inclement weather they stayed home and ‘conversed’. Social media is NOT human interaction and cannot create close friendships. Although this may have had some possible benefits (such as falling teenage pregnancy and drinking) the downside will be human loneliness: the lack of interaction in the flesh.

Balance is required – such an obvious thing. The internet is an amazing tool and over the years I have met amazing people via the Internet, including my husband almost 20 years ago – it was the power of the written word.

Nothing though can ultimately replace face to face relationships and friendships and society is doomed if one simply lives online.

Best comment of the day

MY Post disappeared, but it likely was good to kill it as I am prone to say exceedingly critical things of young people (deserved, but then not everyone needs to have their faults publicly pointed out, as it can be harmful rather than constructive,)

anyway, “This is perhaps best captured by the boomer-led “Great Reset” “you will own nothing and you will be happy””.

Not Boomer led! Claus Schwab, Davos, Sun Vally, Donor Class, Soros, Social Media/Tech Billionaire, and the rest of The Global Elites led. It is the cold words that we all will become property of the state. It is the warning call to a New Feudalism, where all live on basic UBI, housing given as assistance, likely based on ones ‘Social Credit Score’, holidays will mass attended resort complexes with stays earned by points and include drugs, sun, water, food, and possibility of rutting (travel unethical if done unneeded otherwise). Work will be 90% useless work as some pointless gov functionary 15 hours a week – as the automation makes everything, the software does the office work, and retail is automated and done by driver-less robots and vehicles/drones and private business have been absorbed by Government. Entertainment will be at home streaming virtual reality, ‘Better than Real Life’ with drugs to enhance the artificial pleasure, and your sex/companion robot to act as a simulacrum of fellowship.

The young will love it! It will be like if the phone they clutch 24 hours a day opened up and let them inside, to be in forever, endless, distraction, and banishment of tedium. It will be hell if you are not conditioned to like it though, but the conditioning is going better than planned, the making people solitary, just as project fear is from the covid response. (I have never owned a cell phone, nor used a smart phone, nor will, nor wore a mask, nor will vaxx)

The ‘Great Reset’ is supposedly all about Renewable Energy, that is its basis excuse, how Carbon neutral is going to take change to the very core of society. It is in fact Feudalism. It is The Norman Conquest.

I will explain next if this gets past the mods.

“LESSON SEVEN – NORMAN ENGLAND AFTER THE CONQUEST The reason why the Norman Conquest was so significant is that it changed the entire way England was run. It introduced a new set of rulers, a new ruling system, a new language and a new culture. FEUDALISM One of the most important changes was to do with the ownership of land. William introduced a system of land ownership that was called feudalism.”

William seized all the land

“So he gave land to important people who had helped him to conquer England. These people were called lords or barons. However, they didn’t truly ‘own’ the land.”

The small landowners and freemen under the Saxons ended as land was ‘Nationalized’

“The peasants were not quite slaves. Their barons didn’t own them in the way that Roman slave owners owned slaves. They couldn’t buy and sell the peasants, and they couldn’t kill them. But they could, and did, forbid the peasants to leave the land. In effect, these peasants were ‘tied’ to the land. If their lord of the manor changed, they stayed on the land. These sorts of peasants were called serfs,”

Because the deflationary effect of Tech, automation and software taking physical jobs, and office jobs, everything becomes very cheap, but as so few will have proper jobs a vast number will have no income. This means UBI, and if you know history you know when you take the King’s Shilling you re his man.

Every Central Bank is now developing a Digital Currency (The Chinese digital Yuan now real). This means your Digital Wallet (your phone) is not an account at the Private bank – It is a account with the CENTRAL BANK. Every penny you take in, and goes out, is accounted to and from you, and from and to the other side of every transaction! For ever. UBI will go in, as much as the system thinks you deserve, and you will be theirs for ever. In China there is no street cash use, you must use your phone to buy a snack, or a taxi or bus ride. Your ‘Credit Score’ will be your social credit score. You will borrow from the Central bank, they will give you money, loan you money, based on how you fit the algorithm.

This is ‘The Great Reset’. You may own the clothes you wear, the chair you sit on, but you bought it by digital tokens through the Central Bank, it is not really ownership anymore – your digital wallet may stop working if they wish, money may ‘Time Out’ as they wish to direct your spending patterns, The Great Reset is ‘you will own nothing and you will be happy’, it is serfdom, but a very comfortable one, but very controlled – do not live the way they wish? Your Central Bank Digital Wallet will be adjusted, and you will do as they wish.

The Young people will like it.

i am starting to think that the problem might be partially biological-most people dont seem to have the ‘need to know about’ gene. My wife gets anxious if i do why,why,why too much-as if there is a scary void if one asks too many questions (and often there is…). I think people intuitively know that once you start asking questions you will be led to places that will cause you anxiety and challenge – and people shy away without really understanding why. And yet others of us cant NOT ask why – because I think our sense of security lies in knowing vs unknowing. All the males in my family line seem to have been born with the ‘need to know’ gene and our experience is that we tend to be surrounded by many people with a clear ‘I dont want to know’ gene . So hard to have meaningful conversations about anything and we tend to be looked upon as negative, grumpy blokes. Reading history seems to endorse this-most people are quite sheep like in the face of glaringly clear unpleasantness unfolding etc. As an evolutionary psychologist might say – the sheep gene did allow a high level of genetic transmission whereas the need to know gene tended to cause strife and maybe less successful reproductive success due earlier death etc. Most thinkers i have read tended to be less interested in personal procreation as a survival strategy……………in fact my son had a vascectomy at age 18.

“This is perhaps best captured by the boomer-led “Great Reset” movement and its attendant slogan “you will own nothing and you will be happy”. Implicit in this slogan is the idea that if we could just rewind the clock 16 months, all will be well again.”

No, the Great Reset is the OPPOSITE of rewinding 16 months. It’s about resetting our social and economic systems on a global scale. It’s basically a Marxist egalitarian utopia where the State provides you with your life essentials and own everything – but you rent everything – property, cars, appliances. This apparently will reduce or remove inequality, save the environment and make us all happier. The only part of the Great Reset I think could be of interest is the idea of Stakeholder capitalism rather than Shareholder capitalism, but beyond that I think it’s just another Marxist/Communist fantasy which will result in nothing but misery. Unfortunately according to this article young people are growing ‘more authoritarian’ and have a desire to impose their utopian communist ideals on the world by force (it is already happening and I don’t think it is altogether ‘Boomer led’). Every dictatorship starts with the schools for a reason and decades of indoctrination are now coming to fruition – the West let this happen in plain sight to its eternal shame and damnation.