Long Bets calls itself ‘The Arena for Accountable Predictions’. It’s a website that lets soothsayers and prognosticators test themselves by trying to predict the future, gambling for real stakes.

The featured bet that currently leads the website is between the Astronomer Royal Martin Rees and cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker. Given the events of the last 18 months, this has arguably become the most significant wager of the century so far — even if the stake is a relatively piddling $400.

Rees will win that sum if the following prediction is substantiated:

“A bioterror or bioerror will lead to one million casualties in a single event within a six-month period starting no later than Dec 31 2020.”

The bet’s timeframe — 2017 to 2020 — has expired, but it is not yet settled. As Ross Douthat points out, the bet will only be resolved when it is possible to answer this question: Was Covid-19 an escapee from the Wuhan Institute of Virology, or did it jump from a bat cave to its first human patient? Wet markets or lab-leak?

A real answer to that question will have profound implications: for much of the media, for the standing of the scientific community, and for the Chinese Communist Party, which would look as if it had not only “done a Chernobyl”, but failed to stop this bioerror’s effects from locking down much of the world. All would face a renewed crisis of legitimacy.

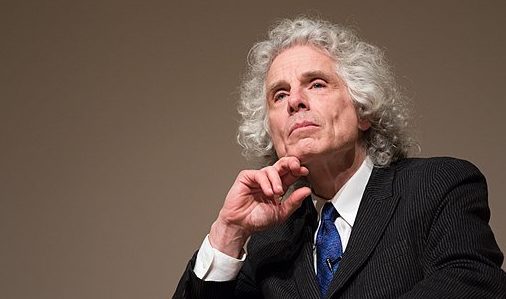

It would also be a blow to Steven Pinker. One of the most prominent intellectuals anywhere, boyish and (somewhat) charming, equipped with unmissable hair, Pinker has spent much of the previous decade patiently outlining all the reasons why the world is getting… better.

Sprawling across a range of topics, from pollution to homicide, war to poverty, Pinker jetted around in the 2010s, armed with slides, graphs, and numbers that, to him at least, proved everything was on the right track. Everything was OK. He was like all those poor Edwardian thinkers who believed world war was imaginable but not at all possible. Pinker’s lovely graphs pointed in one direction: progress. The better angels of our nature were winning out.

When Pinker gave his TED talks, they always reminded me of some eccentric, colourfully dressed professor, explaining the inner workings of his magical chocolate factory to a group of curious school children. Look at the marshmallow fountain my dears! World War Three is impossible! But Pinker had persuasive critics, who accused him of over-interpreting his data.

Martin Rees, on the other hand, has always played on the black keys. ‘Apocalyptic’ undersells the way he thinks about reality. The possibility of existential risk is more important to Rees than how many people are in or out of poverty at any time. Our Final Century? asks the title of one of his books. That’s not a Pinker question.

If a “bioerror” turns out to be responsible for unleashing Covid-19, then it would be wise to pay more attention to those like Martin Rees who treat existential risks seriously, rather than Steven Pinker, who tells a fabulous story about progress, without ever taking a downward glance at reality.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe