A new report from Onward provides fresh insight into a disturbing trend: the decline in support for democracy. Entitled The Kids Aren’t Alright, this isn’t the first study to raise the alarm (for earlier examples, see here and here). However, it does confirm that the slide towards authoritarianism is especially pronounced among young people.

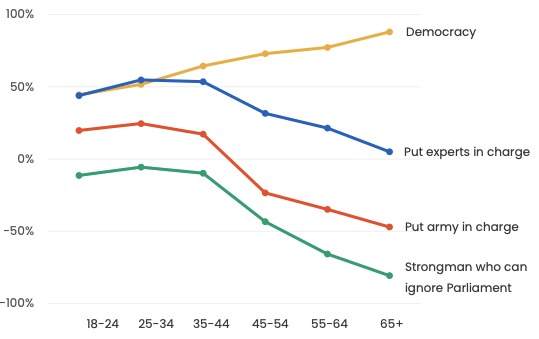

For instance, the following chart shows that the net level of support for democracy is much lower among 18-to-44 year olds than it is among the over-65s:

Support for alternative ways of running the country — i.e. putting experts in charge, or the army, or a “strongman” leader — is correspondingly higher among the younger age groups.

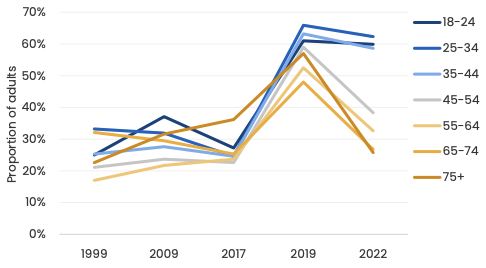

In a 2019 report, also from Onward, people were asked about “having a strong leader who does not have to bother about parliament”. The results revealed a spike in support for this option among all age groups. However, this was at a time when the Government was paralysed by the Brexit deadlock in the House of Commons. So perhaps the authoritarian surge was just a temporary reaction to the parliamentary chaos.

Thanks to the new study, we can see what has happened since. Though support for the “strongman” solution has indeed subsided among the older age groups, it remains disturbingly high among the young and young-ish:

Is this a response to the 2019 general election? After all, older voters (who skew Conservative) got the result they wanted, while younger voters (who skew Labour) did not. On the other hand, we’re talking about a rally in support for “putting the army in charge”. I somehow doubt that a bunch of disappointed Corbyn-supporters were responsible for that.

The new report also shows that the anti-democratic trend is strongest among non-university educated young people and those with the most socially conservative views. Though there may be a fashion for finger-wagging wokery among some students, it is not this that’s driving the authoritarian drift.

For liberals of all kinds, there’s a lot to worry about here. There’s clearly a growing demand for radical change, one that could be exploited by anti-liberals of the Right or Left. For an example of what might happen, just look to France where politicians like Marine Le Pen and Jean-Luc Mélenchon owe their success to the votes of the young.

However, populism in British politics has so far been shaped by politicians of a rather different sort. The likes of Nigel Farage, Richard Tice and Laurence Fox are libertarians by instinct. During the pandemic they stood in opposition to lockdown — even though the weight of public opinion was for much stricter measures than those imposed by the government.

Furthermore, British populism has appealed much more to grumpy old men than to angry young men — as can be seen by the breakdown in support for UKIP at its 2015 electoral zenith. As UKIP leader, Farage’s saloon bar persona was ideally suited to these demographic contours.

Much the same could be said of the parties, personalities and media outlets that constitute British populism in 2022. As a package it’s not compelling. Therefore, even if they wanted to mobilise the UK’s young authoritarians, our populist leaders are facing in entirely the wrong direction. And for that, British liberals should be truly grateful.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeNigel Farage will never get the credit he deserves for saving British democracy. For those of you who voted Leave, you will likely remember the dark days of early 2019 when Theresa May delayed Brexit and it looked like anti-Brexit MP’s could form a majority to reverse it through a parliamentary coup. I can’t speak for others but I was seething at these MP’s and privately thought them traitors to their country and fellow citizens. If they got their way, I was prepared to vote for the most hardline, extreme right wing party I could find on the ballot paper. They could have had a manifesto commitment to line these MP’s up against a wall and have them shot and I would have voted for them.

Fortunately, Nigel Farage stepped in with his Brexit Party and provided us with a moderate alternative in the nick of time. I and millions of others voted for that wonderful party resulting in May being removed from office and more hesitant MP’s to line up behind their manifesto commitment to take us out of the EU. Democracy worked and was saved in this country by Farage. His critics owe him a huge debt.

I couldn’t watch the news for 6 months during that period – it was just too difficult seeing anti-democratic forces taking over parliament.

Looks to me like the anti-democratic sentiment drops off pretty sharpish once people get past 40 (the grey 45-54 line pretty much follows the yellow 55+ lines). Isn’t this just a rehash of those who aren’t socialists at 20 have no heart, those that are at 50 have no brain?

I imagine people are also more likely to vote when they get older so become more invested in the democratic process. Young people has this bad habit of not voting.

I was struck by the difference between Nigel Farage and XR. Nigel Farage had an agenda. He formed a party, made speeches, got votes and made a difference, democratically. XR by contrast are an anti-democratic group of bullies.

There was a photo of XR protesters in the house of commons glued to speaker’s chair. They had a poster which said “Citizens Assembly Now”. Isn’t that what we call Parliament?

Nigel Farage is a hero. They ought to give him a knighthood or peerage.

So the generation that came of age around the time of the credit crunch, who have endured stagnant wages, insecure gig economy employment, large student debts, rocketing rents and falling home ownership rates due to soaring prices are most likely to favour a change to the system. Whereas the older cohort who enjoyed high home ownership rates, much more secure employment and more generous pension schemes and who have seen their pension and wealth protected via the triple lock are much more likely to favour the status quo?

Who’d have thunk it!

Bull… those us who are now in the older categories grew up in an era of massive unemployment & inflation. We endured the fuel crisis which is remarkably similar to the current gas crisis

don’t tell me we had it easy and the youth of today is hard done by

And they want to give sixteen year olds the vote.

We don’t support democracy because it is effective. It is rarely a good form of government and will rarely be as ‘good’ as a good dictator. The problem with ‘good’ dictators is getting enough support to get power and that they very rarely stay good for long.

Democracy is an acceptance that it will likely be rubbish but nothing like as bad as a dictator will probably be.

As Churchill said ‘democracy is the worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.…’

I’m quite disturbed by the twenty five percent in my age bracket who favour a strong leader over Parliament. No fool like an old fool.

I see no problem with the politics of Jean-Luc Melenchon. I would certainly vote for his party if I lived in France.

Put the monarchy back in charge.

Yes indeed Prince Charles would be an ideal dictator! Er…you were joking weren’t you?

No. The system we have now does not work. At all.