In April, French voters gave Emmanuel Macron a second term as president. Yesterday, they voted in the first round of elections to the National Assembly — i.e. the French Parliament.

According to Le Monde, the centrist “Together” block headed up by Macron’s LREM party, which came a clear first in 2017, has been narrowly beaten into second place. Just ahead of them in votes (but not seats) is NUPES — a broad-based coalition of Left-wing parties. By far the biggest component of this grouping is Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s anti-establishment LFI party — the other members are the Socialists, the Greens and the Communists.

Expect the success of this “progressive alliance” to be held up as an example for the British Left to follow.

However, it’s worth pointing out that with about a quarter of the vote, the combined share for the French Left is not significantly greater than it was in 2017 when the parties ran separately. It’s mainly because the Macronistes did significantly worse than five years ago that the two blocks have drawn level.

In terms of votes, the biggest winner last night was the far-Right. In 2017, Marine Le Pen’s National Rally got just 13% in the first round and Éric Zemmour’s Reconquest party didn’t even exist. In 2022, the two parties combined got close to a quarter share of the vote — so not far behind the Left-wingers and the centrists.

The biggest losers, meanwhile, were the parties of the centre-Right, led by the Republicans. In another terrible result for French conservatives, they sunk well below the 15% level.

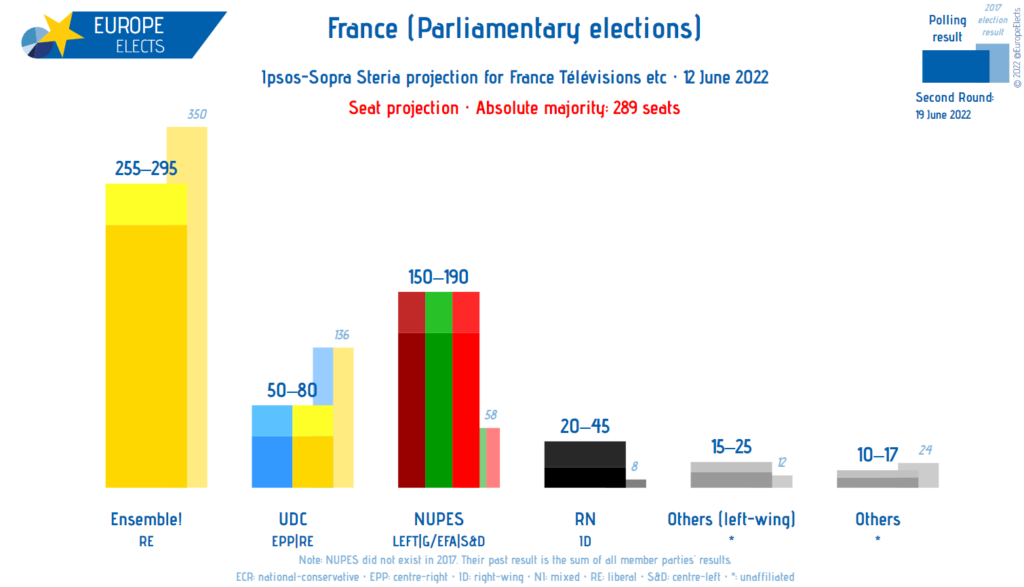

So how might these various vote shares translate into seats? Initial projections have been made (see chart above), but these are uncertain until after the second round in a week’s time. What we can be sure about is that the results will be far from proportional. The two round system favours the centre over the extremes. The far-Right does especially badly because, even if a candidate makes it through to the second round, there’s an anti-populist majority in most constituencies.

By not cooperating in the first round, the two populist parties have also reduced their chances of getting through to the second round contests. Most notably, Zemmour has fallen at the first hurdle — and thus won’t be elected to the National Assembly. In contrast, by standing aside for one another, the Left-wing parties will be represented in the great majority of second round contests, which will boost their seat tally at the expense of Macron’s allies.

It is possible that Macron will not have a majority in National Assembly — and with Mélenchon leading the opposition that would prove disruptive. The president may find himself relying on the goodwill of the conservative deputies because, though much reduced in number, they could end up holding the balance of power.

The lines of a new French political system are beginning to emerge. On the Left, a barely coherent — yet strengthened — opposition. In the centre, and on the moderate Right, a liberal president and his erstwhile conservative opponents who increasingly need one another. And, finally, on the far-Right, a populist movement capable of gaining votes but not power.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeEmmanuel Macron should work with Marine Le Pen to establish an alliance between the “Together” block (lead by LREM) and National Rally in the parliament. He should appoint her as Minister of the Interior and give her free reign on matters of immigration. She will improve the quality of life in France by deporting illegal aliens and halting further immigration from the Middle East and Africa.

Supported by MPs from Natonal Rally, Macron can continue his economic reforms and military reforms. The latter is an ongoing project to establish a European military structure that is independent of NATO. Such independence will be vital for the security of the European Union after the United States, due to open borders, ceases to be a Western nation by 2040. It will be a Hispanic nation (i.e., a nation in which Hispanic culture is dominant).

Get more info about the immigrant problem in France.

M.M

You obviously know very little about France’s political landscape.

Macron started what is now called “ Ensemble” poaching members from the left and from the right…..call the latter, republican conservative if you will and forget the GOP meaning. No way in the universe any “ republican” parties, aka, attached to values on which the French Republic was founded, no party would touch Le Pen with a pole to have her in a coalition. Sending people on flights to Rwanda would send the country in flame…..except for the far right who sees this as jolly good idea. In my view, ideas are neither good or bad…..they either work or don’t and this one, sure as egg, wouldn’t.

The vast majority of who you call migrants are…..French citizens. Tell me how to kick them out even if a lot of them would deserve to be. Secondly…..we do the job of stopping the others for you. Personally, I would be happy to see all these coppers stationed in Calais be re dispatched where they are needed….that is in French suburbs where law and order has just about disappeared. You could then show us how you deal with this influx.

Melenchon may be trumpeting his victory…….and now accusing the government of cooking the figures…..both parties are on absolute equality today and the fact remains that :

1/ He is a clown about whom even Alexis Tsipras says that he doesn’t really want to rule….now talk of someone who knows a thing or 2 about radical speech. He is just having a lot of fun pretending and bellowing speeches that make Fidel Castro look like a ball of fun. It is always the same grandiloquent blabla.

2/ He will never get the majority in Parliament and his partners in crime, the old socialists will find it very very hard to vote against European values they’ve always believed in. Even the communist Fabien Roussel, who I rather like, not so much his ideas is already saying he was to keep is freedom of speech. Because, make no mistake, Melenchon is not some who lets one poppy rise above him. You should have seen these guys and girls last night when he made his…..lol….victory speech. Like little school boys and girls all lined up behind him.

3/ Macron will get his majority, maybe not absolute, but by all means relative, meaning he will have to deal with the republicans ……and personally I think it is a good thing. The French parliament will start like looking like a parliament again.

President Mitterand on his second term didn’t get the full majority and said it wasn’t good that one single party should get the majority.

The French constitution was written in 1958, very tough times for the country on the brink of civil war, the army rebelling, numerous attempts on de Gaulle life. 64 years later, it is a different country. However, retooling the constitution is something o one really dares or wants to do in the fear to open a can of worms.

Media love drama……they’ve had Covid to scare us s…….s, presidential vote heralding the return of Hitler s daughter, the war in Ukraine…..and now the parliamentary vote. Keep cool and carry on, France will always be the mess it always was which never kept Brits, Dutch etc to buy a home there and enjoy the cheap wine.

The outcome for France of an anti-President movement is worrying – new political paradigms often get off to a shaky start.

In the UK I fear that Boris Johnson and the Conservatives could be replaced by a Blue/Green coalition of Labour, the Lib Dems, the SNP and the Greens. My expectation is that ‘the coalition’ would rapidly descend into disunity as their internal differences pulled parties apart.

Red-green? Red-orange-yellow-green?