It’s cold outside. In the 10 years that I have lived here, I do not think I remember seeing so much snow coverage in London. The markets are feeling the cold too: over the weekend the energy markets recorded record prices. On Sunday, the price for power at peak time (5-6pm) for the following day hit £2,586 per megawatt-hour — a record. It appears that promises of a warm winter were greatly exaggerated.

This is not surprising to anyone who studied the data for temperature and for winter gas demand. The first and most obvious thing to note is that warmer weather in the period September to November does not predict warmer weather in December. For example, in the years 2015-21 the warmest September to November period was recorded in 2021 (11.7°C), but this was followed by a very average December (6.3°C). Meanwhile, the warmest December in this period, recorded in 2015 (9.6°C), was preceded by a very average September-November period (11°C).

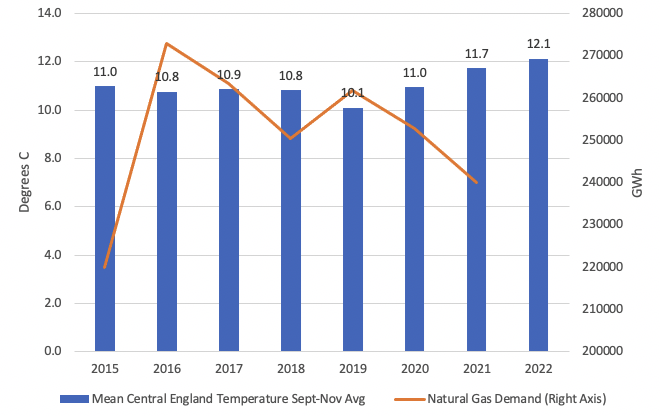

When natural gas demand is added into the mix, the waters only become more muddied. The chart below shows September-November average temperature by year together with gas demand in the fourth quarter.

While it is true that 2022 saw higher-than-average temperatures in this period, it was not that much higher than, say, 2021. Did we really expect a 0.4°C increase in autumn temperatures to save us from a major energy crisis? What’s more, there is clearly no reliable relationship between autumn temperatures and autumn-winter gas demand. Gas demand was lowest in autumn-winter 2015, yet seasonal temperatures were about average. Gas demand was highest in 2016 yet, once again, temperatures during that period were roughly average.

The other thing that stands out in the chart is that gas demand does not fluctuate all that much. The largest surge we saw in gas demand in this period (2016) was only around 8.5% higher than the period average, while the largest decline (2015) was only around 12.5% higher than average.

But now, with temperatures plunging, we are running out of road. How will politicians respond? Most likely, they will pull another rabbit out of the hat and blame the looming recession, telling us that the recession will reduce energy demand. This, too, does not stand up to scrutiny. During the last major recession (2008-09), GDP growth contracted 4.2% in Britain while gas demand only fell 6.7%. By contrast, in 2011, when the economy was humming along at 1.5% GDP growth, gas demand fell almost 17%. As with autumn temperatures, GDP growth is a bad predictor of gas demand.

At the end of the day, the energy crisis is a real crisis. It is not a crisis of perception. The simple fact is there is not enough gas. Either we figure out a way to get more or we substitute the gas for another energy source; otherwise, we are in a great deal of trouble.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribePoliticians did not fail to foresee this crisis. They decided that other objectives were more important and they quite deliberately chose this path. We should not accept the consequences of deliberate action being framed as an accident or miscalculation.

Politicians did not fail to foresee this crisis. They decided that other objectives were more important and they quite deliberately chose this path. We should not accept the consequences of deliberate action being framed as an accident or miscalculation.

The idea that experts wouldn’t foresee an annual event is laughable, and gives far too much benefit of the doubt. All of this is intentional.

The idea that experts wouldn’t foresee an annual event is laughable, and gives far too much benefit of the doubt. All of this is intentional.

Sadly, people of power and influence are not going to take this problem seriously until there really are power cuts, and people die in large numbers because of their ideological fantasies about “renewables” and zero carbon.

This site is quite the most interesting viewing especially when things get a bit sticky as they are at present. Each of the dials has an explanation box if you roll your pointer over it. Our plucky wind turbines are providing 3GW, which is better than the 1GW yesterday morning.

G. B. National Grid status (templar.co.uk)

That is the problem, as much as wind can produce a lot of energy, it does not do so reliably. Without some form of mass energy storage, wind is not much of a solution.

The least power from wind is always mid-winter and mid-summer. That is when the wind doesn’t blow. And when electricity demand is highest.

The least power from wind is always mid-winter and mid-summer. That is when the wind doesn’t blow. And when electricity demand is highest.

Yes Mick, I often look at that site and also this one –

https://gridwatch.co.uk/

which shows much the same information. I think it comes from the same source. I find it interesting to look at the amount of electricity we are importing and exporting. It’s quite often the case that we are importing and exporting at the same time. The other thing I’ve noticed is that over the last week 3 – 4% of our electricity has come from coal fired power stations. Usually that figure is much less than that and often zero. I assume the fact that we are burning coal is an indication that we are approaching a limit.

Last year maximum demand was 47.1 GW. The maximum demand this winter so far is 46.98 GW.

Yes Steve it can become a bit addictive at times like this – a few days still to go I think.

I also think you’re right about the limits especially in what the grid can handle – I think we’ll find some subsidies have been handed out to ensure the coal fired power stations (such as they are) have come on line.

As Andrew says above we need grid scale batteries that can store a couple of weeks supply – a very big ask, although policy seems to have been based on the assumption that they’re already here.

Yes Steve it can become a bit addictive at times like this – a few days still to go I think.

I also think you’re right about the limits especially in what the grid can handle – I think we’ll find some subsidies have been handed out to ensure the coal fired power stations (such as they are) have come on line.

As Andrew says above we need grid scale batteries that can store a couple of weeks supply – a very big ask, although policy seems to have been based on the assumption that they’re already here.

That is the problem, as much as wind can produce a lot of energy, it does not do so reliably. Without some form of mass energy storage, wind is not much of a solution.

Yes Mick, I often look at that site and also this one –

https://gridwatch.co.uk/

which shows much the same information. I think it comes from the same source. I find it interesting to look at the amount of electricity we are importing and exporting. It’s quite often the case that we are importing and exporting at the same time. The other thing I’ve noticed is that over the last week 3 – 4% of our electricity has come from coal fired power stations. Usually that figure is much less than that and often zero. I assume the fact that we are burning coal is an indication that we are approaching a limit.

Last year maximum demand was 47.1 GW. The maximum demand this winter so far is 46.98 GW.

This site is quite the most interesting viewing especially when things get a bit sticky as they are at present. Each of the dials has an explanation box if you roll your pointer over it. Our plucky wind turbines are providing 3GW, which is better than the 1GW yesterday morning.

G. B. National Grid status (templar.co.uk)

Sadly, people of power and influence are not going to take this problem seriously until there really are power cuts, and people die in large numbers because of their ideological fantasies about “renewables” and zero carbon.

Drax has restarted 2 coal powered plants. We should keep them in operation and open some more mothballed ones. We should start mining coal again in the UK and importing coal from trusted partners and run these power stations until the day comes that nuclear or fracking or energy storage for wind power has increased to the point that they can be safely decommissioned.

Time for the return of a government that doesn’t believe in fantasies.

Absolutely. I’d like to see some investment in thorium molten salt reactors, but that’s not likely to happen due to the high initial costs.

Safer, significantly reduced issues of disposing waste and with estimates of about 1000 years supply of the stuff, it surely ticks all the boxes. Other than cost.

Absolutely. I’d like to see some investment in thorium molten salt reactors, but that’s not likely to happen due to the high initial costs.

Safer, significantly reduced issues of disposing waste and with estimates of about 1000 years supply of the stuff, it surely ticks all the boxes. Other than cost.

Drax has restarted 2 coal powered plants. We should keep them in operation and open some more mothballed ones. We should start mining coal again in the UK and importing coal from trusted partners and run these power stations until the day comes that nuclear or fracking or energy storage for wind power has increased to the point that they can be safely decommissioned.

Time for the return of a government that doesn’t believe in fantasies.

I think we’re long past the point where we can expect any western govt to implement a logical and coherent energy policy. We can only hope energy shortages create minimal death and destruction before politicians figure it out.

If they haven’t figured it out yet then they never will. They are in hock to an ideology. They will see the light only when they start to lose their seats in serious numbers. Then they will pretend that it was nothing to do with them.

If they haven’t figured it out yet then they never will. They are in hock to an ideology. They will see the light only when they start to lose their seats in serious numbers. Then they will pretend that it was nothing to do with them.

I think we’re long past the point where we can expect any western govt to implement a logical and coherent energy policy. We can only hope energy shortages create minimal death and destruction before politicians figure it out.

Caught between a rock and a green place !

Caught between a rock and a green place !

There’s plenty of gas, only problem is that its buried underground in one form or another.

The sooner politicians get over the suicidal rush to greenwash themselves the better.

It’s more that the nord streams have been blown up and Europe has no Russian gas anymore to be honest. Lng is more expensive, has to shipped, has to be refined on delivery etc etc oil next, joy. This crisis is because of the sanctions on Russian energy, you can’t just replace that easily over night.

It’s more that the nord streams have been blown up and Europe has no Russian gas anymore to be honest. Lng is more expensive, has to shipped, has to be refined on delivery etc etc oil next, joy. This crisis is because of the sanctions on Russian energy, you can’t just replace that easily over night.

There’s plenty of gas, only problem is that its buried underground in one form or another.

The sooner politicians get over the suicidal rush to greenwash themselves the better.

The decision by Centrica to decommission it’s massive gas storage facility – called ROUGH and runs out under the North sea in Yorkshire, cannot be overlooked in this. This was a private sector decision to increase short term profit. I believe it’s now being re-commissioned, albeit cannot get back to what it did quickly and certainly not for this winter (but at least for the following). But someone closer may be able to confirm

Govt could probably have interjected and insisted this did not happen, but they were v happy for the free market to make it’s own decisions. National security and the potential for Putin to use Russia’s obvious leverage, esp when Londongrad was offering further advantages in Tory support, never came into it.

Yes. The political decision to allow it to be decommissioned was incomprehensible in terms of national security and the catastrophic effects if the domestic gas grid ever empties out.

The commercial decision by Centrica is also looking ropey- they would have made a fortune selling cheap stored gas into the present market. Perhaps they thought things never change (like the German bureaucrats smirking at Trump) or that they’d only be hit by a windfall tax if things got bad.

Yes MN. Do we know if any Centrica Board or Exec leads lost their job as a result of this decision? i.e: has there been a consequence. It’s fascinating how, given the energy crisis and it’s impact on folks this winter, that so little spotlight has been shone on this.

I doubt it JW. Anyway I hold the politicians(May’s government?) much more to blame than the Company – national fuel security is not really within their remit.

I doubt it JW. Anyway I hold the politicians(May’s government?) much more to blame than the Company – national fuel security is not really within their remit.

Yes MN. Do we know if any Centrica Board or Exec leads lost their job as a result of this decision? i.e: has there been a consequence. It’s fascinating how, given the energy crisis and it’s impact on folks this winter, that so little spotlight has been shone on this.

Yes. The political decision to allow it to be decommissioned was incomprehensible in terms of national security and the catastrophic effects if the domestic gas grid ever empties out.

The commercial decision by Centrica is also looking ropey- they would have made a fortune selling cheap stored gas into the present market. Perhaps they thought things never change (like the German bureaucrats smirking at Trump) or that they’d only be hit by a windfall tax if things got bad.

The decision by Centrica to decommission it’s massive gas storage facility – called ROUGH and runs out under the North sea in Yorkshire, cannot be overlooked in this. This was a private sector decision to increase short term profit. I believe it’s now being re-commissioned, albeit cannot get back to what it did quickly and certainly not for this winter (but at least for the following). But someone closer may be able to confirm

Govt could probably have interjected and insisted this did not happen, but they were v happy for the free market to make it’s own decisions. National security and the potential for Putin to use Russia’s obvious leverage, esp when Londongrad was offering further advantages in Tory support, never came into it.