In recent weeks, as the huge cost of “zero-Covid” lockdowns have highlighted China’s growing economic fragility, a flurry of articles has arrived speculating about the potential political weakness of Chinese president Xi Jinping.

The Wall Street Journal, for instance, has for several months now been arguing that there are “widening grievances within the party over Mr. Xi’s policies,” and that where once “Xi Jinping seemed all but invincible,” now “his push to steer China away from capitalism and the West” has “exposed faint cracks in his hold on power.” The Financial Times, similarly, has portrayed Chinese leadership has deeply divided over economic and Covid policy. Others have indulged even more salacious rumours of Xi’s imminent departure.

Sharp internal policy divisions in Beijing may indeed exist, and this is interesting and worth considering. But we should beware that such eager speculation, if taken too far, probably says more about ourselves than about political realities in China.

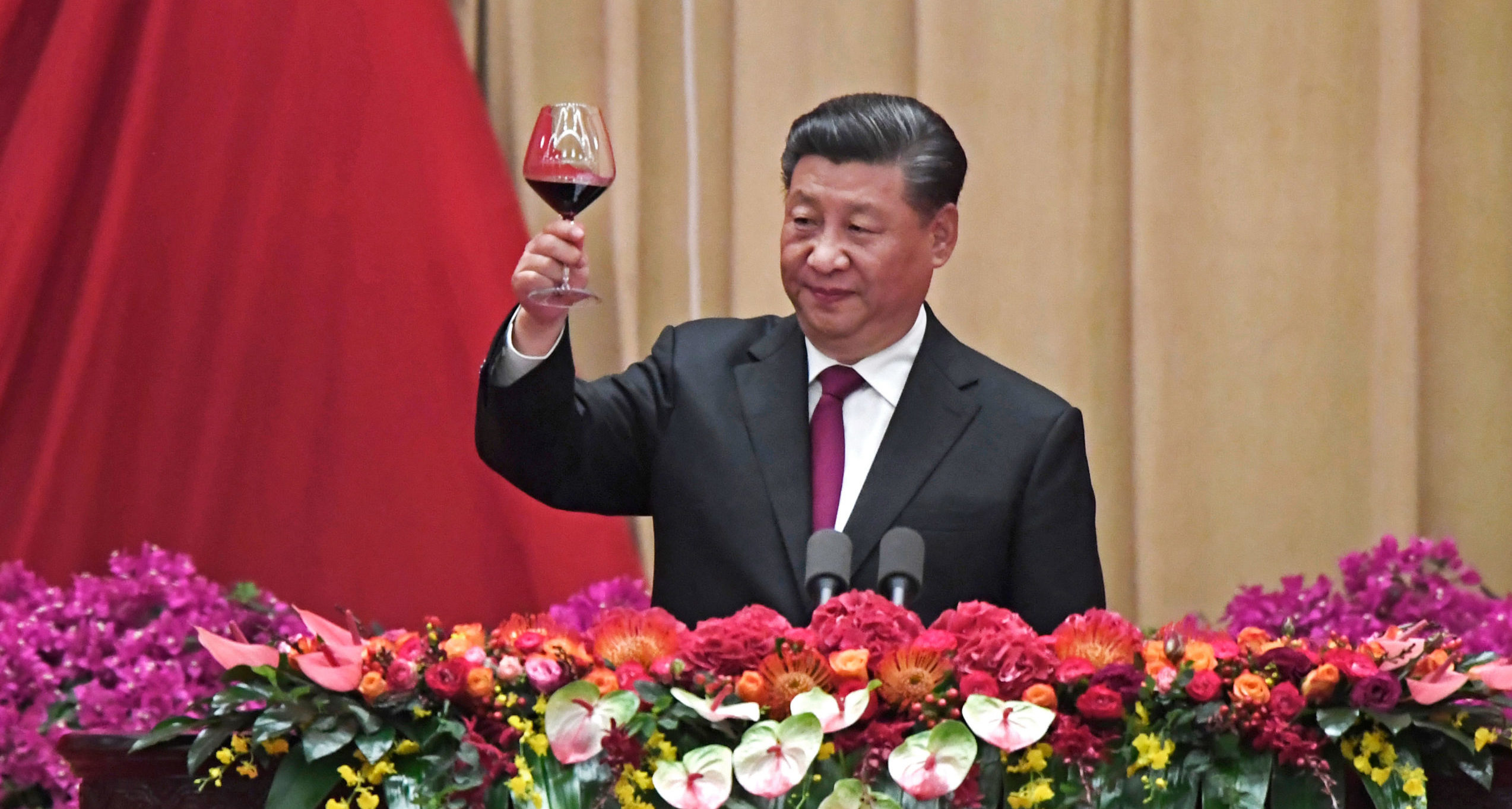

Xi Jinping is in no real danger of losing power. His whole political method since 2012 has been to seize control over what Christopher Johnson, former head China analyst at the CIA, has described as the three key “levers of power” within the “Chinese ‘Deep State’.” Using a ruthless “anti-corruption” campaign as a knife, he was able to quickly break his rivals’ hold over the military, security services, and party bureaucracy (i.e. the HR department, essentially), and aggregate control over them entirely into his own hands – where they still very much remain. This means a little public discontent or elite financial distress is not going to meaningfully weaken Xi’s grip. Moreover, he retains the powerful force of popular Chinese nationalism to lean on in any period of real difficulty.

It is true that China’s current self-inflicted economic difficulties could pose a cost to Xi within the internal politics of the party. But this is likely to take the form of not promoting quite as many factional allies as he would have liked at the upcoming 20th Party Congress this November. Shanghai Party Secretary and devoted Xi sycophant Li Qiang’s career may or may not in some trouble, for example — this is of interest to Chinese politics nerds such as myself, but it would hardly represent the spectacular collapse of the Xi regime.

One can’t help but suspect that something more is contributing to the current excitement over Xi’s possible political headaches: that Cold War atmosphere lingering in the air these days thanks to Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine and the West’s economic isolation of Russia. Not only are hopeful rumours of impending coups in the Kremlin now regularly aired in Western news media, but the rather ambitious goal of instigating Putin’s removal from power seems to in fact be de facto U.S. government policy.

A chance to retell ourselves the familiar story of the West’s Cold War experience, in which authoritarianism inevitably collapsed and democracy prevailed, is of course an irresistibly comforting one. And we’d love to tell ourselves that story about China too.

N.S. Lyons is the author of The Upheaval on Substack.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe