The results of the French election showed a resounding Macron victory. Yet Marine Le Pen increased her share of the vote in the final runoff from 34% in 2017 to 42% in 2021. This score in turn dwarfed her father’s shocking 18% performance in 2002 which brought a million demonstrators out on the streets. Though Macron suffered from incumbency and a weak economy, he benefited from the fact that many of the issues that favour national populism were in abeyance.

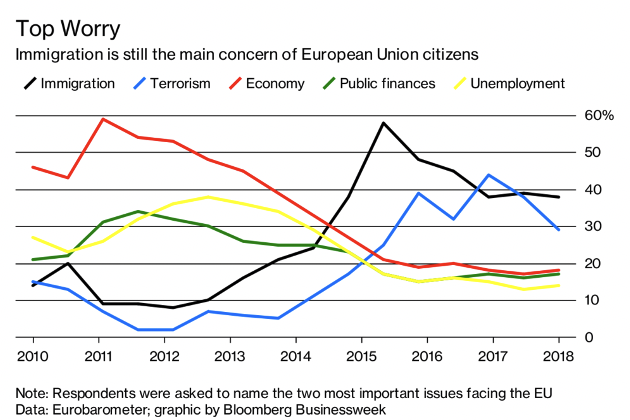

For instance, research shows that when immigration is a high-ranking priority for voters, national populist parties benefit. On issues where people trust technocratic expertise, such as foreign policy, combatting Covid or managing the economy, fewer voters look to populists. These issues tend not to be prioritised by populist voters, nor do they predict populist voting. Populists attempting to seize on the Covid issue have fallen flat.

As the figure below shows, when the economy is performing well and foreign policy questions or Covid are not dominating the headlines, technocratic mainstream parties are less advantaged and there is more room for the rise of cultural issues that favour Right-wing populism. Prior to the populist moment of 2014-17 in Europe and America, economic questions had declined in importance among voters.

On this view, Le Pen could have come closer (as Norbert Höfer did in Austria in 2016), perhaps even scoring an upset, had circumstances been similar to those of 2015.

The deeper structural drivers of national populism, whether with Trump, Brexit or Le Pen, lie in ethnic majority discomfort with the scale and pace of cultural change, supplemented by concerns over the integration of Muslims (though this is not the main factor). Culture war questions over the boundaries of free speech and content of national history are adding another layer to political contestation in American politics, and this could also begin to affect European politics.

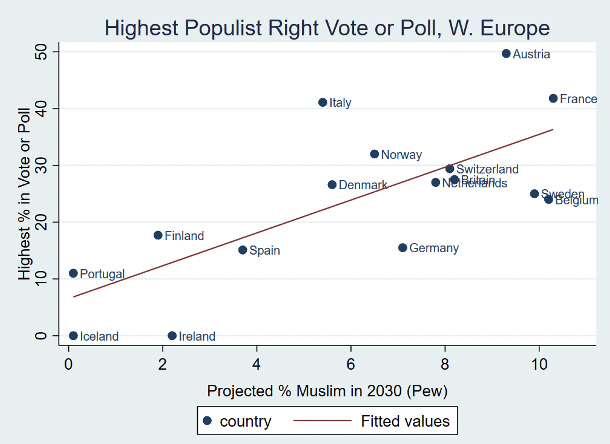

This said, national populism’s potential is limited by a ceiling of strongly motivated opposition. The only question is whether this limit lies above or below the 50% mark. One way of getting a sense for where the potential lies is to examine the relationship between ethno-demographic scale and change, as indicated by Pew’s projected Muslim share of a West European country in 2030, and the high-water mark of support for the populist Right.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeWhat are the closest historical analogies to what’s happening today in the West? What happens when an ethnic majority is rapidly (in historical terms) replaced with one or more minorities?

Is there a historical precedent for a wealthy, prosperous elite turning against less affluent/educated members of its own ethnicity and promoting unrestricted immigration to dilute out the formerly dominant ethnic group?

Nope.

Western ethnomasochism is unprecedented.

In some other cultures elites have looked down on the majority, going so far as to adopt another language or subscribe to a mystery cult; but none deliberately sought to displace the very people from which the elite itself had sprung.

That in essence is the sickness of the West.

One aspect of Prof Kauffman’s very good analysis that nobody will discuss is the demographic explosion happening in Central Africa.

The population of Africa is due to quadruple by 2100. Populations currently double every 25 years. Nigeria, one of the most unsustainably growing countries, has a population of over 200 million, and will be 400 million in the next 25 years.

There are already no jobs for the majority of the 200 million there, and no plan, or capable government, to deal with the next wave of 200 million people.

These demographic changes will drive key geopolitical conflicts across the continent, but also transform European politics beyond recognition. 200 million people attempting to immigrate to Europe will either cause Europe to become African, or make it deeply isolationist. I cannot see another option on the horizon.

Unfortunately neither left nor right will talk about this reality, much less propose sensible solutions to it.

Such discussions have been going on for a long time on certain websites. I should know.

Steve Sailer has a graph from the UN revised in 2019 showing the projected population growth of sub-Saharan Africa. He’s called it for several years the world’s most important chart.

If you haven’t seen it (I’m pretty sure you have) Google “Steve Sailer’s Most Important Graph.”