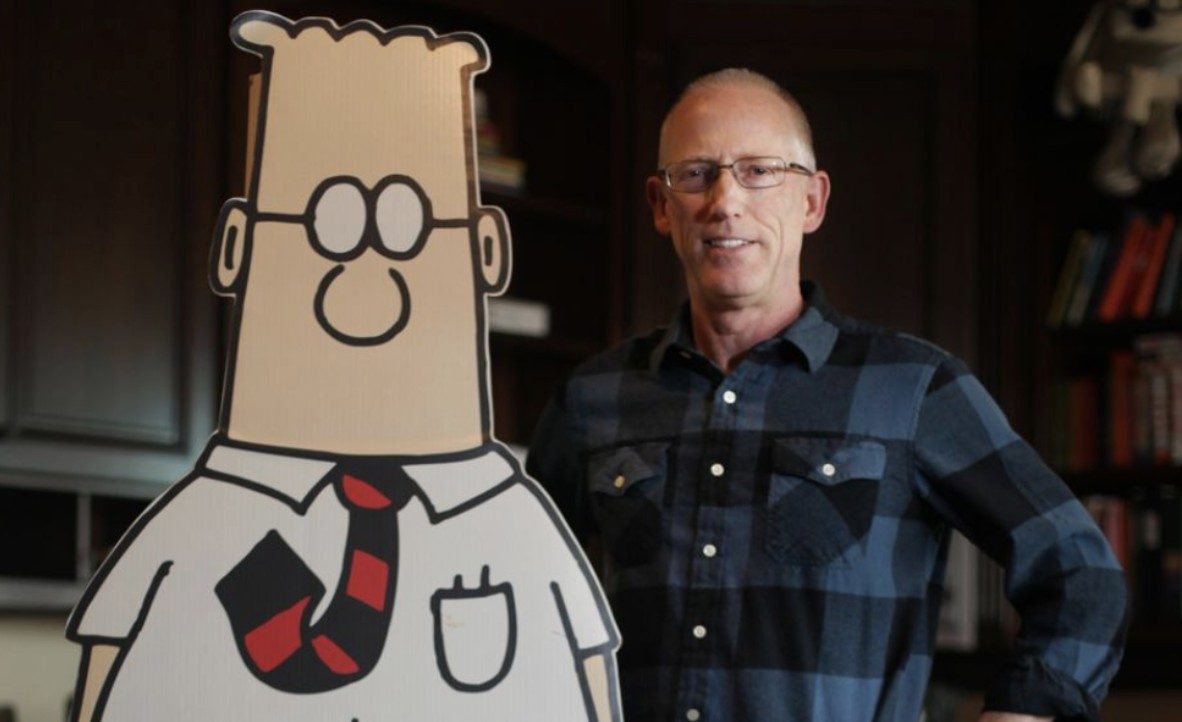

Scott Adams, who has died aged 68 of metastatic prostate cancer, was for decades one of America’s most successful cartoonists. His comic strip Dilbert appeared in over 2,000 newspapers across 65 countries, generating an empire of calendars, coffee mugs, and corporate training materials. Adams was not a Bill Watterson, labouring over every panel of Calvin and Hobbes as high art; he was closer to Jim Davis, churning out a reliable, competently-drawn product that told the same jokes over and over. Dilbert was bland, inoffensive, and omnipresent. Office workers pinned it to their cubicle walls without thinking much about the man behind it.

That changed in 2015. When Donald Trump descended the golden escalator at Trump Tower, most commentators dismissed him as a clown. Adams saw something else. As a self-described trained hypnotist, Adams recognised in Trump what he called a “Master Persuader” operating at a level he had never witnessed in public life. He began blogging about Trump’s techniques with the enthusiasm of a fellow practitioner spotting a virtuoso. Trump’s “Build the Wall” slogan, Adams argued, was genius precisely because it was visual and directional rather than literal.

Adams’s analysis gave a certain kind of voter permission to support Trump. Here was a successful, seemingly rational boomer with an MBA from Berkeley, not some talk-radio crank, explaining that Trump’s apparent buffoonery was actually strategic brilliance. Adams predicted Trump would win the Republican nomination when Nate Silver’s FiveThirtyEight gave him a 2% chance. He predicted Trump would win the general election in a landslide. When Trump did win, Adams became a minor celebrity in MAGA circles, publishing Win Bigly: Persuasion in a World Where Facts Don’t Matter in 2017.

Adams’s journey from Dilbert to political commentary didn’t come out of the blue. He had always harboured unconventional views. His 2001 novel God’s Debris and 2004 follow-up The Religion War explored an oddball pandeistic theology. He had questioned the Holocaust death toll in 2006 and compared women to “children and the mentally handicapped” in 2011. But these provocations existed merely at the margins of his public persona. It fell to Trump’s hypnotic appeal to bring them to the centre.

By 2020, Adams had transformed his morning coffee-drinking livestream into a full-time political commentary operation. “Real Coffee with Scott Adams” featured a parade of conservative guests discussing everything from immigration policy to election fraud, with Adams belatedly changing some of his views, as on Covid-era safetyism, after a fairly public airing of views. In January 2023, he declared that “the anti-vaxxers clearly are the winners” and admitted he had made the wrong choice in getting vaccinated. “The smartest, happiest people are the ones who didn’t get the vaccination and they’re still alive,” he said. “I did not end up in the right place.” When he was diagnosed with prostate cancer in May 2025, some of his followers attributed it to the vaccine he took.

His final break with what’s left of the mainstream came a month after those vaccine comments. Reacting to a Rasmussen poll that asked respondents whether they agreed with the statement “It’s OK to be white”(a slogan the Anti-Defamation League associates with white supremacism), Adams declared that black Americans were a “hate group” and advised white people to “get the hell away from black people”. Newspapers across America that were still carrying Dilbert responded by dropping it, and Andrews McMeel Syndication terminated his distribution deal. Adams rebranded the strip as “Dilbert Reborn” on his subscription website, continuing until hand paralysis forced him to stop drawing in November 2025.

Adams’s trajectory follows a pattern we’ve seen generally in the context of the online Right’s fracturing: figures who once served as bridges between mainstream conservatism and its fringes, such as Tucker Carlson, eventually find themselves captured (or convinced) by the audiences they cultivated. Adams started as a translator, explaining Trump to sceptical normies in the language of business-book psychology only to end as a participant won over by active engagement with the discourse he had once claimed to observe from above when offering his earlier against-the-grain predictions about Trump.

In his final statement, composed on New Year’s Day 2026 and read by his ex-wife Shelly Miles after his death, Adams wrote that he had given his life “everything I had.” He asked that any benefits from his work be paid forward, and said he had loved his audience “to the very end”. Whether they had led him or he had led them remained, as with all questions of persuasion (hypnotic or otherwise), unclear. What is clear is that this audience was, with perhaps a few exceptions, not the one he had cultivated in the Nineties. Adams’s life ultimately illustrated how the tools of persuasion can reshape not only audiences, but the persuader himself.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe