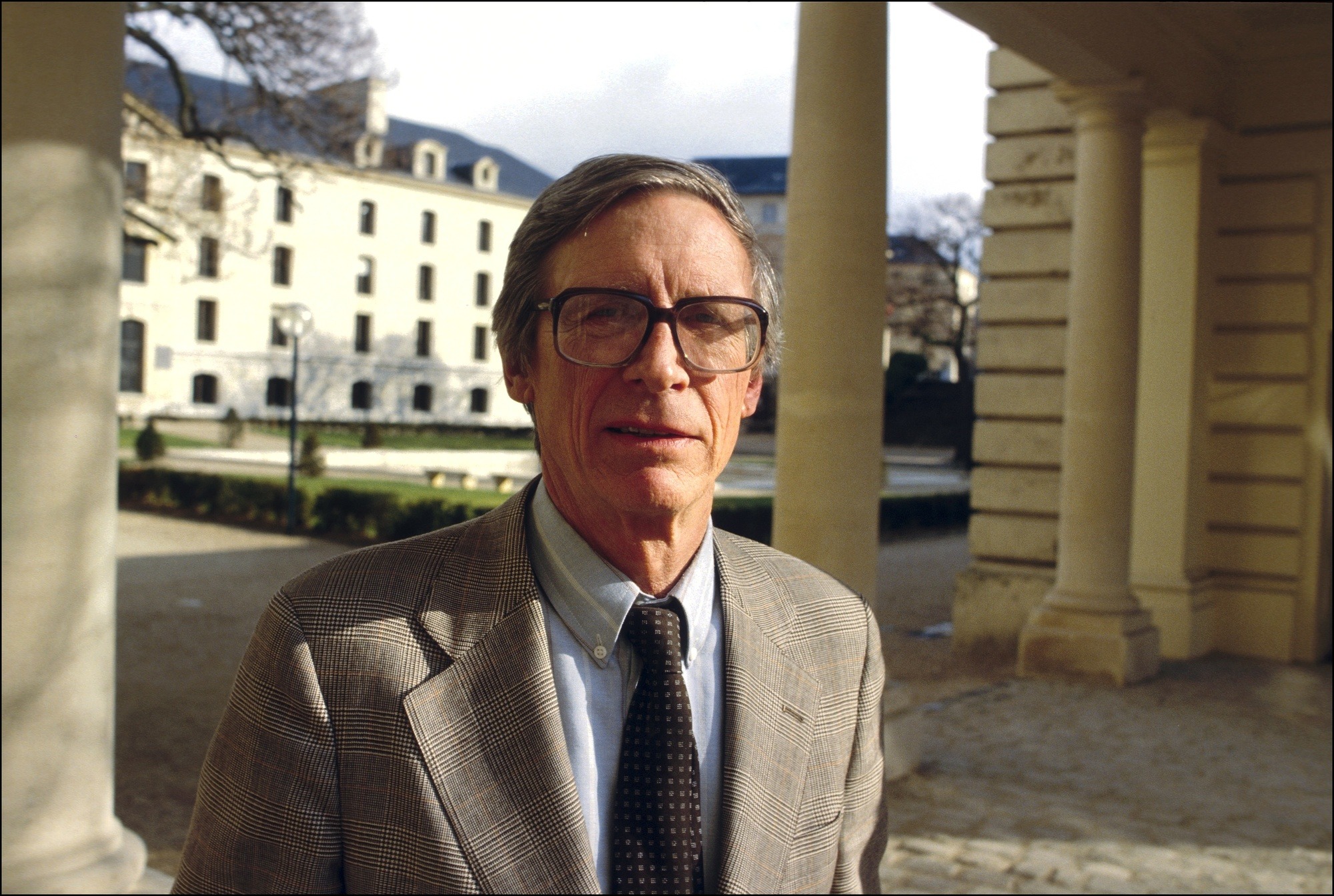

A fascinating article in the Boston Review casts a critical eye over the legacy of philosopher John Rawls.

Such was the success of Rawls’ work, culminating in “A Theory of Justice” published in 1971, that even the criticisms of it came to be understood in terms defined by his famous idea of “justice as fairness”. In the libraries of Princeton and Oxford, Rawls’ version of liberalism came to be hegemonic, the philosophical basis for the ‘end of history” idea – that the big ideas had been sorted out and future debate was now only about the details. But those underlying presumptions are now being questioned again.

“As the concerns of philosophers were consolidated, facility with Rawlsianism became the price of admission into the elite institutions of political philosophy.”

Katrina Forrester – herself an assistant Professor of Government and Social studies at Harvard – has thrown down a gauntlet to the all-pervasive Rawlsianism of her profession. Her new book, In the Shadow of Justice: Postwar Liberalism and the Remaking of Liberal Philosophy, from which this article is taken, argues that Rawls’ ideas began to dominate the academy at just about the moment when they were no longer relevant to the social problems being experienced by the Western world. The all-encompassing nature of Rawlsian Liberalism meant that as the liberal project began to take a radical neo-liberal and technocratic turn, too few political philosophers were sufficiently awake to the consequences.

“The 1960s, when Rawls put the finishing touches to his theory, was the age of affluence, civil rights, and the Great Society, but it also marked a period of urban crisis and mass incarceration, and the beginning of a new era of deindustrialization and financialized capitalism in which public investment was cut and the labor movement quashed.”

The subsequent financial crisis, the rise of populism, to these problems the great Rawlsian project had little to offer – just more of the same.

“The story of Anglo-American liberal political philosophy is therefore not just a tale of philosophical success. It is also a ghost story, in which Rawls’s theory lived on as a spectral presence long after the conditions it described—and under which it emerged—were gone.”

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe