The case of Yang Tengbo, the alleged Chinese spy with links to Prince Andrew, comes at a sensitive time for Sino-British relations. Things have deteriorated dramatically since David Cameron’s premiership, when the two countries enjoyed a so-called “Golden Era” of diplomacy. But the pandemic, trade wars, the erosion of democracy in Hong Kong, and the persecution of Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang have all complicated bilateral relations. By the time Rishi Sunak was in Number 10, he was calling China a “threat to our open and democratic way of life”.

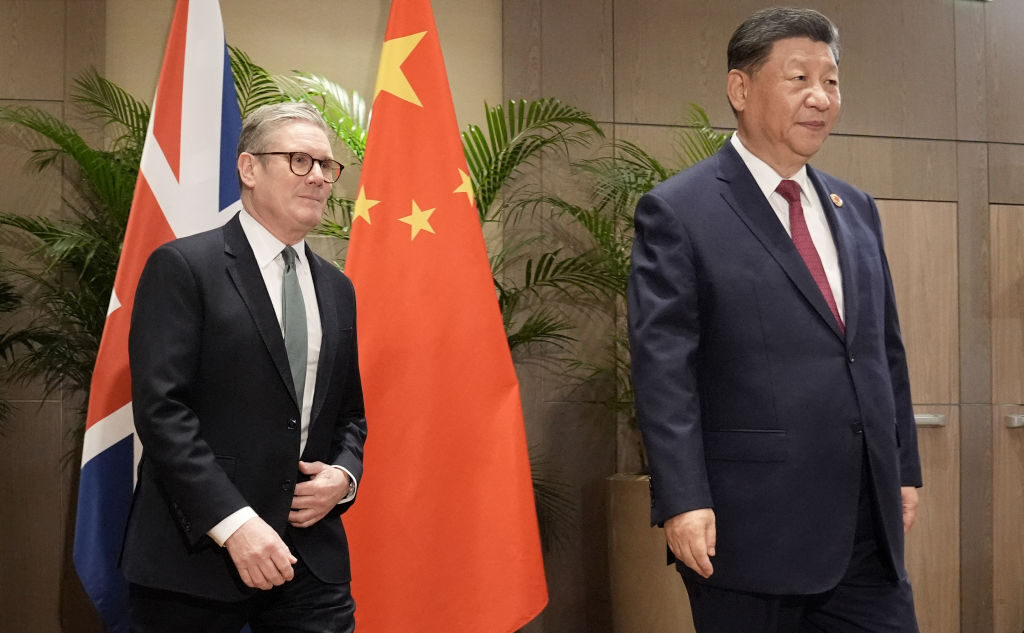

The priority of the current Labour government is to improve Britain’s economy, which contracted slightly in the two months leading up to December. The brutal fact is that China, whose economy was half the size of Britain’s when Hong Kong was handed back in 1997, today outstrips it five times. It is too big to ignore, and yet also complicated to engage with: therein lies the UK’s quandary. It also explains the changes which Keir Starmer’s government has spearheaded.

Other Western nations are also having to confront the problem of how to deal with China. Even the mighty US has recently reported that, per the suspicions of analysts, its Government cyber systems have been deeply penetrated by Chinese actors. This is the result of a decade of investment from Beijing, with the goal of increasing its technical capacity. That, in turn, was prompted by reports in 2012, following the Edward Snowden leaks, that America had managed to gain access to some Chinese systems.

The UK may heed America’s likely approach under Donald Trump when he is inaugurated again in January. Everything he has said, not to mention his actions during his first presidency, makes it clear he is seeking a new deal with China, and that security issues are part of that mix. Trump wants access to the Chinese market, better trade with US goods, and clear wins that can help him declare America is winning again.

In the UK, China is still a relatively small investor and, while a significant trading partner, hardly its largest. From China’s perspective, the UK is a middle ranking power: not a negligible one, by any means, but not a priority. There are many areas of technology in which China is fast moving well ahead of the UK. Last year alone, China committed about £360 billion to research and development. In contrast, Britain’s most recent Budget set aside only £20 billion.

The UK might believe that it has a range of options when it comes to China, but pragmatists have powerful arguments on their side. If the country wants to seriously address its economic challenges, it needs to have dynamic agreements and relations with the largest global economies. Even with the current challenges it is facing, China still belongs to that group. Some British politicians can certainly berate Beijing for its moral and political sins, but there has to be some sort of dialogue. There are things about which Britain needs to be well-informed and prudent when it deals with China, but to have nothing to do with Beijing is not a realistic option. On AI, the environment, and global economic growth generally, the decisions made by Xi Jinping will have an impact on the UK whether our leaders like it or not.

That means that however embarrassing and irritating the Yang case is, it is extremely unlikely to stop Chancellor Rachel Reeves going to China in January to restart economic dialogue. Nor will it prevent Starmer’s likely visit later in 2025. Britain needs a cadre of clued-up, effective politicians and public voices who are strategic and skilled about the specific difficulties and opportunities of dealing with China.

There are still many aspects of relations between the two that are asymmetric. British companies experience disadvantages in China that Chinese companies largely avoid in trading and coming to the UK. Achieving reciprocity and fairness in the relationship is necessary, and stoking paranoia by claiming that there is a Chinese secret agent on every street in Britain will be little help. Politicians must realise that China is there whether we like it or not, and any policy that dreams it away is not only ineffective but doomed.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe