Photo by Edi Ismail/NurPhoto/Sipa USA

It is known that sheep can recognise as many as fifty human faces. Now some Cambridge University researchers have trained eight Welsh Mountain ewes to distinguish between photographs of actors Jake Gyllenhaal and Emma Watson, former United States President Barack Obama and BBC newsreader Fiona Bruce. Professor Jenny Morton, the study’s lead author, said this proved these creatures are “capable of processing a two-dimensional object as a person”.

The fact some sheep can distinguish a white female television presenter from a black male former president may not seem big news, especially in our turbulent world. “Face recognition is a sophisticated process,” added Morton. “But they’ve got big brains, they see other sheep, and they use this processing to recognise one another.” No doubt to defer accusations of academic absurdity, her team insisted this might help research into human ailments by aiding efforts to monitor new drugs given to sheep with mutations of Huntington’s disease.

Yet even on its own terms this study should make us pause for thought. Sheep are seen as simple animals, their gregarious social nature giving rise to derogatory expressions in our language. Now we are told the face-recognition skills of these ruminants are similar to those of advanced primates such as monkeys, apes and, yes, humans. This small study is one more tiny step forward in our understanding of the natural world. And each time we learn a little bit more, it raises fresh questions over our relationship with animals.

Perhaps you have been entranced by The Blue Planet II, the BBC’s latest amazing adventure into the oceans. The first instalment alone revealed a fish changing sex and another leaping from the sea to snatch birds. The most surprising scene, however, was an orange-spotted tusk fish methodically fetching a clam then carefully prising it open on a special piece of coral. “I think we have all been quite staggered by the physical and cognitive abilities of a lot of the animals,” said Rachel Butler, the sequence director. “I don’t think any of us were quite prepared for what we would find down there.”

Once it was thought use of tools distinguished humans from animals. Now we find even fish use them to get breakfast. These creatures are sentient, smart and sometimes social, performing tasks that match some of our own from co-operative hunting through to complex face recognition. In his fine book What A Fish Knows, the ethologist Jonathan Balcombe reveals a goby can memorise the topography of a tidal pool in one take while a squid can navigate a maze faster than a dog. “A fish is an individual with a personality,” he concludes, arguing that they can plan and learn, soothe and scheme, experience moments of pleasure, fear, playfulness, pain, possibly even joy:

“A fish knows and feels.”

Move higher up the animal kingdom and we find more shared traits. Studies have found chickens can delay gratification, pigs play video games, octopuses unscrew lids from jars and elephants grieve for their dead. Cetaceans (aquatic mammals) seem to have ability to feel emotions, share language and perform complex tasks together. Learning from past experiences was long seen as another hallmark of human beings – yet rats, chimpanzees, dolphins and even some birds display signs of “episodic memory” skills.

The concept of cognitive superiority has been entrenched in human outlook for thousands of years. From farming to medical research, from circuses to zoos, this belief informed our approach to animals as we captured them, imprisoned them, slaughtered them, tortured them and ate them. Yet what if we are wrong and, as some scientists suggest, homo sapiens just possess an alternative form of intelligence? And what does it mean if we are discovering that animals share many traits long thought to define our species?

Peter Singer, the Australian moral philosopher, first raised these issues more than 40 years go in his groundbreaking book Animal Liberation. Yet the more that is discovered by scientists – even something moderately amusing, such as that sheep can distinguish between two film stars – the questions he posed on animal suffering back in 1975 become all the more pertinent. And these issues become increasingly hard to ignore when millions can see a humble fish using tools and more advanced marine life on shared hunting expeditions in a popular television programme.

I gave up eating octopus when I began diving and saw these incredible molluscs in their natural environment. The more I read about them, with their brains and alien-like biology, the more wedded I become to my decision. More recently, I have come to the conclusion zoos are indefensible. Scientists have found animals in captivity display forms of depression, distress, passivity, stress and stereotypical behaviour, despite the noble efforts of many keepers to stimulate them. Few animals in zoos are really endangered, while one David Attenborough documentary offers more by way of education than most of these prisons that exist largely for our entertainment.

Then there is the thorny issue of industrialised farming. The ability of humans to keep feeding ourselves despite soaring population is one of the most amazing aspects of development. Growing global demand for protein, especially, is a sign of progress, underscoring the reduction in poverty and fuelling the stunning growth in life expectancy. Yet it comes at a cost. First, the overuse of antibiotics in animal husbandry that endangers modern medicine, which relies so heavily on these drugs. Second, the devastating environmental impact. And third, in animal misery caused by our insatiable appetite for meat.

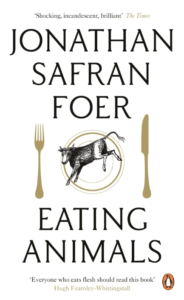

Yet the more we discover about animals, the less justification for factory farming. If even fish feel pain, and incarcerated animals suffer extreme stress from disruption of their natural social order, how can we tolerate treating them with such cruelty? Pigs are smarter than dogs – but most Britons who happily munch on ham and pork would be horrified at the idea of dining on poodle. Yet as the novelist Jonathan Safron Foer observed in his book Eating Animals, “every factory-farmed animal is, as a practice, treated in ways that would be illegal if it were a dog or a cat.”

Yet the more we discover about animals, the less justification for factory farming. If even fish feel pain, and incarcerated animals suffer extreme stress from disruption of their natural social order, how can we tolerate treating them with such cruelty? Pigs are smarter than dogs – but most Britons who happily munch on ham and pork would be horrified at the idea of dining on poodle. Yet as the novelist Jonathan Safron Foer observed in his book Eating Animals, “every factory-farmed animal is, as a practice, treated in ways that would be illegal if it were a dog or a cat.”

There is a moral inconsistency between our reverence for some species such as cats and dogs, our wonder for the natural world unfolding on our television screen and our wilful blindness to the incredible suffering of sentient beings to ensure a ceaseless supply of eggs, milk and sausages. The end is seen as justifying the means, as with so many other terrible things in history. Meat is not necessarily murder but from life to death, the fate of millions of farm animals should not be seen as something that is the preserve of cranks and fanatics.

We recoil with horror over bear-bating and cock-fighting. I suspect one day we will look back with equal distaste not just at elephants in zoos and circuses, but at cows turned into milking machines, sows stuffed into breeding crates and battery chickens crammed in cages too small to spread their wings. This is institutionalised abuse of animals – and it becomes less acceptable with each new academic study offering fresh insight into other creatures sharing our planet. From fish to sheep, they are all rather closer to us than we once imagined.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe