There are many reasons why the nation’s finances are in a mess, but one of the most significant is the rise of economic inactivity. This is distinct from — and worse than — unemployment, because its victims aren’t even seeking work.

In the UK there are 700,000 more working-age people who are economically inactive than there were before the pandemic. Some are in full-time education, but most are on benefits and costing the country dear. What’s especially concerning is that the British situation is uniquely bad. In all other G7 nations, employment levels are higher now than before Covid.

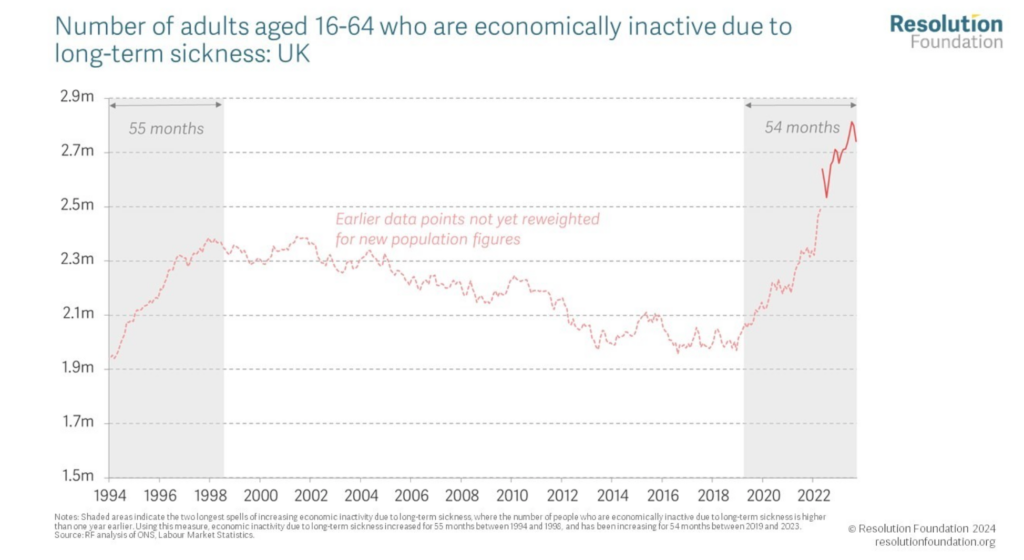

A new briefing paper from the Resolution Foundation delves into the causal factors. The most important is the dramatic rise in the number of people claiming benefits because of long-term sickness — in particular, mental health conditions. Frustratingly, this comes after a long decline in sickness-related inactivity.

So what went wrong? The glaringly obvious explanation is the effects of lockdowns during the pandemic. However, report author Louise Murphy argues that our national turn for the worse began in the summer of 2019: “it does not appear to be a short-term, Covid-19-related blip.” Fraser Nelson makes a similar point, tweeting that the “rise in sickness benefit started about a year before Covid.”

On the face of it, Murphy and Nelson are correct — the change from a downward to an upward trend does happen many months ahead of the virus. Yet it’s vital that we don’t shift the blame away from the pandemic — or, for that matter, the policy response to it.

For a start, we shouldn’t over-interpret the precise point at which economic inactivity begins to rise. A quick glance at the above chart shows that there are many minor variations around the long-term trend. The fact that an uptick happened shortly before the pandemic — when, by the way, the world economy was slowing down — could be coincidental. There’s no reason to assume that it explains the much bigger changes that took place during the pandemic.

In any case, prior to Covid, there was no sudden deterioration in long-term sickness trends that can explain the 2019 rise in economic inactivity. The Office for Budget Responsibility’s 2023 Financial Risks and Stability report (page 28) does show a long-term rise in self-reported disability, but that started years earlier.

Page 24 of the same OBR report also shows that the contribution of long-term sickness to inactivity levels was low at the beginning of the pandemic, only to grow in significance until it became the dominant factor by 2023. Again, this suggests that what happened during the pandemic was more important than anything which came before it.

And no wonder. For this country, Covid-19 was the most disruptive and deadly event since the Second World War. Sickness, bereavement, confinement and enforced worklessness affected millions of people. Unsurprisingly, the impact lingers.

Of course, we weren’t the only country to suffer. So why has the recovery in UK employment levels been so much slower than our competitors?

Paradoxically, the explanation may be the rapid progress that was made getting people off benefits and into work in the decade before Covid. The reforms pioneered by Iain Duncan Smith during his long tenure as Work and Pensions Secretary were controversial, but effective. Since he left the job in 2016 he’s had no fewer than eight successors — and one can’t help but think that this absurd lack of continuity has weakened the Government’s resolve to keep Britain working.

Certainly, the pandemic found us out. While we’ve continued to create jobs — enough to absorb record levels of immigration without any increase in unemployment — hundreds of thousands of British citizens have been consigned to a life on sickness benefits. After 14 years of Tory rule — which began with such ambition — it is a sad and ignominious conclusion.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe