A perverse part of me wishes, on behalf of Hollywood Bowl England, to applaud the council’s plans to squash a smug independent landmark. (Credit / Rowans)

I will not go to Finsbury Park

The putting course to see

Nor cross the crowded High Road

To Williamsons’ for tea

For these and all the other things

Were part of you and me.

John Betjeman’s “The Cockney Amorist” is a touching, if hokey, account of taking in the town with a lover. It is the Londoner’s answer to Rodgers and Hart’s “Manhattan”, in which the great big city’s a wondrous toy just made for a girl and boy. In both New York and London, simple pleasures are just good enough, but Betjeman’s poem is maudlin, the lover anticipating being jilted and left to walk the streets alone. He knows that each cheap yet characterful pastime will remind him of the one who got away. The city is built on those places — peculiar old holes that seem at once communal and personal, timeless and specific.

I have a growing sense that the cockney amorist, were he to have been dumped today, would have no such problem. For by the time he had the chance, hands in pockets, to whistle past a pub where he and his darling had whiled away an afternoon or a market where they had shared a kiss, the local council would surely have authorized a nine-story complex of flats where they stood. Soon, anyone with a poignant memory of Rowans Tenpin Bowling in Finsbury Park will not have to endure a similar ache, since Haringey Council has determined that the land would be better used for 190 new homes.

From the Londoners I know, it seems an awful lot of people will be spared the bother of memory, free to stroll past without association. Whether it’s a first kiss at a teenage birthday party or a cocaine-fueled caper with a beautiful Costa Rican DJ, every Londoner of a certain age seems to have had a suspiciously formative night at Rowans. They speak of it as if it were as London as the Pearly Kings.

First opened as a bowling alley in the late Eighties, a seedy irony attached itself to Rowans when it started hosting club nights in the Nineties, which often went on without end. At the waning of Cool Britannia, about the time that Suede detected a “Crack in the Union Jack”, Rowans offered an appealing niche, being a bit rubbish, a bit multicultural and a bit chic. Its patrons ranged from Craig David to Prince Edward — a B-list rogues’ gallery of tabloid Britain. I once heard someone promise that Rowans will be the best and worst night of your life. That promise has persisted through the gentrification of the local area, so that you will now hear the younger generations with higher-waisted jeans drawl, “Yah, Rowans”, too.

Buildings look different when you know they may not last; just like people, really. It was with that in mind that I approached Rowans on a rainy Tuesday night. It was the week before Christmas, and I could not but observe it as if it were gamely battling an illness. Elderly relatives often hold on ’til Christmas and croak at the dinner table, and a similar stench of death lingered by Rowans. The bowling alley sits opposite Finsbury Park station, and occupies a mess of a building erected in the late 19th century as a tram shed. Dressed a little shyly in hollow wet scaffolding, it was hardly making the most of its unusual period assets. Beneath, it had an American boardwalk quality, with ugly neon lights illuminating offers of discounts for parties.

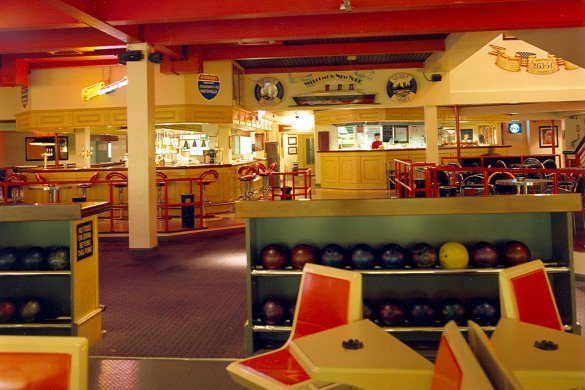

That, over 150 years, a tram shed could house a cinema, a dance hall, a bingo hall, a snooker club and then a bowling alley — all good Mass Observation activities for a traditionally working-class neighborhood — tells you something of the building’s coherence. In keeping with that versatility, Rowans now trades on being all things to everyone: it has an arcade, a pool lounge, a bar, a karaoke booth and a nightclub. It is Brighton by the tube, you could say.

As a non-native of the capital, I could have a chip on my shoulder about Rowans. For while Londoners can bore away about their misspent youth safe in the knowledge that everyone appreciates the cultural relevance, blank faces greet my stories of provincial nightlife. A perverse part of me wishes, on behalf of Hollywood Bowl England, to applaud the council’s plans to squash a smug independent landmark. One foot in the door of Rowans, however, and any resentful non-Londoner sheds their inner bumpkin and begins to sing, “Knees Up, Mother Brown”. There is dated charm everywhere. Why, in the age of automation, is a small man in a booth employed to supervise a turnstile entry? It is the most useless job in the city, redolent of those Italian attendants who sell you loo paper by the sheet outside public toilets, and I envied his folly. He was ripe for slow cinema.

Beyond the turnstile, an amusingly long corridor adds to the mystique of windowless Rowans. The walls are yellowed, the thin carpet has a hideous pattern, and the lighting is low. At the other end, the clientele hogging the tuppenny nudgers are hardly the diverse, class-straddling community that relics from the Nineties speak of with misty eyes, but all seem cheery. Most are the same old recent graduates one sees at the Faltering Fullback down the road. Everyone bowling, and queuing to bowl, does so very politely.

Upstairs at Rowans was a different story, where 12 further lanes of bowling were reserved for a special group. There, youth was replaced by experience, quarter zip by bowling shirt, and mullet by a duck’s arse ’do. The booming De La Soul from downstairs was but a rumble, and the lighting was lifted. The bowling was serious, the focus rather than the adornment. A ball guttered resulted in a furious slap of the forehead. A floor above the competitive socializing, there was a community fighting for a pleasingly tarnished silver trophy.

I approached with interest, but a firm hand gripped my shoulder and held me back. “Professionals only,” said a tall security guard, who slightly tightened his vice when I explained that I wished to talk to said professionals. “Would you walk on the pitch during a football match?” he barked.

He had something of a point, so I peeled him off and retreated to the bar at the rear of the upstairs lanes, where one of the contestants was on his refreshment break. He was an old teddy boy in an Elvis t-shirt, the King’s face so stretched over his gut that the trademark lip curl had turned into a scream. I asked him how his game was going, to which he replied it was not his night as he tensed the fingers of his bowling hand.

Bowling is a dreadful sport, dull because it expects you to score. It’s like football if football were only penalty shootouts. Given that he was holding his own bespoke bowling ball, I did not tell the old ted that, for fear of being bludgeoned in a bowling alley like Paul Dano in There Will Be Blood. I instead broached the subject of a different demise: Rowans. “Not a sensible idea,” he said, rather calmly. “They’ll just piss off the community. Have they got nowhere else to build?” In a nod to the season, he could have been asking, “Are there no prisons?”

I asked him where, if not at Rowans, he would bowl. He said: “I don’t know. Maybe on my own.” It rather eerily recalled Robert D. Putnam’s Bowling Alone, a sociological essay in which the writer identified the activity with social disconnection. If Rowans were to go, I could hardly see the crowd from upstairs lugging their balls over to Lane7.

The sentiment is timely. One could imagine a military map face up on a table depicting the independent venues under threat across the capital. On the western front, there is the historic Shepherds Bush market, which is threatened with an especially concerning retail wonderland, while to the east, Hackney’s Moth Club is under siege. There are smaller skirmishes over hipster food markets in Elephant and Castle and Brixton that were always meant to be temporary, though the worry is more about what will take their place.

“Have they got nowhere else to build?” is nimbyism, and yet, have they not? Rowans has twice before had to resist overtures from the council, relying on op-eds and petitions to survive. Haringey council does not own the land, but it seems mighty set on incorporating it into its plans. In a “response to all the hoo-ha” on social media, Rowans has insisted that “We ain’t going anywhere”. The same message was relayed to me by the toilet cleaner, who told me that the rumours were “fake news, bro” while replacing a urinal cake. I hope he is right. Places such as Rowans are what make London. Where else is an old teddy boy going to bowl? Where else is a cockney amorist going to get his heart broken? Where else am I going to go tomorrow?

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe